A new procedure may preserve fertility in kids with cancer after chemo or radiation

Children with cancer not only endure chemotherapy or radiation treatment but they may also face infertility in adulthood. Now a new procedure, just proven in monkeys, may be close to use in humans.

Cancer in children was often a death sentence in decades past, but new therapies have saved their lives. Many of these treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation, however, made them infertile. Now, new research is showing one strategy to preserve their fertility so that someday they can have their own biological children.

Many childhood cancer survivors have remained beyond the reach of current assisted reproductive technologies because they are not able to produce mature sperm or eggs. Adult patients have the option to freeze eggs or sperm before treatment and use those samples in the future to achieve pregnancy using assisted reproductive technologies. Unfortunately, those options are not available to children who are not yet able to produce mature eggs or sperm.

Now I and my colleagues in the Orwig lab at the Magee-Womens Research Institute of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Cancer have developed a next-generation reproductive technology by figuring out how to preserve fertility in pediatric cancer patients who might face infertility after chemotherapy or radiation.

Pediatric cancer therapies

About 40,000 kids undergo cancer treatments each year, and 80 percent of children will survive and can look forward to a full and productive life. The bad news is that treatment comes at a cost: About 30 percent of adult survivors of these childhood cancers discover that their lifesaving cancer treatment had an unintended side effect – infertility. Cancer survivors report that fertility is important to them, and while adoption or other family building options are available, those options are not always accessible or desired.

In our current study, we used a juvenile male macaque to test whether it was possible to collect and then freeze immature testicular tissues – which produce mature sperm only after puberty.

We began our experiment by surgically removing this tissue from macaques, which we immediately froze. As the animals neared puberty, the testicular tissue was thawed and grafted just under the skin of the same monkey’s back or scrotum.

The grafts matured during the next several months under the influence of pubertal hormones from the brain. The grafts grew and produced testosterone, which is required for sperm production. We retrieved the testicular tissues eight to 12 months after the grafting procedure, dissected it and discovered that all of the grafted tissue produced mature sperm.

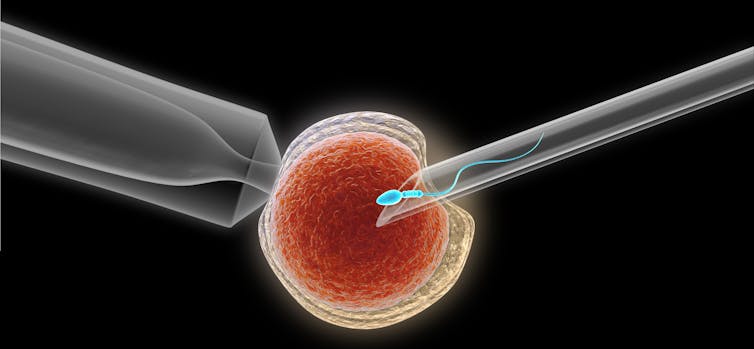

My team then collected this sperm and sent it to our collaborators in the Assisted Reproductive Technology Core of the Oregon National Primate Research Center at the Oregon Health and Science University, who injected it into an egg from a female macaque – a procedure called intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

We then checked the eggs to see which ones were successfully fertilized by the sperm. Eleven of the resulting embryos were transferred into six surrogate female macaques, resulting in one pregnancy that produced a healthy baby girl that we named Grady, which stands for graft-derived baby.

This is the first study to prove that sperm from frozen and thawed primate testicular tissue grafts were able to fertilize eggs and produce a healthy baby.

Implications for the human fertility clinic

The freezing and thawing aspect is important because a prepubertal cancer patient may need to keep their testicular or ovarian tissue in frozen storage for years or even decades before they need them for reproductive purposes.

Combined with nearly two decades of work by other researchers in mice, pig and monkey models, we believe that our results provide important preclinical safety and feasibility data to justify translating this technique to the human fertility clinic in the next two to five years.

I believe we owe this to our patients who have already accepted the risk of testicular biopsy surgery and trusted us to develop next-generation reproductive therapies.

Academic centers around the world, including the Fertility Preservation Program of UPMC, are freezing testicular tissues for boys and ovarian tissues for girls in anticipation that those tissues can be matured in the future to produce sperm or eggs and biological offspring.

There is one documented case of an adult survivor of a childhood cancer who had a baby after her frozen ovarian tissues were transplanted back into her body. There are no documented births from frozen testicular tissues. Our group has been freezing testicular tissue for boys and ovarian tissues for girls since 2011 and has preserved tissues for nearly 250 patients (206 testicular tissues and 41 ovarian tissues).

Therefore, our laboratory is committed to responsibly developing the next generation of assisted reproductive technologies that will allow our patients to use their tissues to achieve their reproductive goals.

All patients should be informed about the reproductive side effects of their medical treatments and about options to preserve their fertility immediately at the time of diagnosis.

Kyle Orwig receives funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development.

Read These Next

Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

The ‘equal time’ rule has been around for a century and aims to promote broadcasters’ editorial…

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

Trump administration axed nutrition education program that saved more money than it cost, even as go

Every dollar spent on community health education through SNAP-ED saved an estimated $10.64 in Medicaid…