Why victims of Catholic priests need to hear more than confessions

Sex abuse by Catholic priests may be as devastating in many cases as sex abuse by a family member because of institutional betrayal, two trauma psychologists write. It calls for special measures.

Pope Francis has criticized U.S. Catholic bishops for how they handled the pervasive sexual abuse of children by predatory priests. He even called for a new management method and mindset in dealing with this crisis. Most recently, the pope summoned presidents of every bishops’ conference from around the world to come to the Vatican on Feb. 21 through 24 for a meeting on how to respond to the pervasive scandals.

As trauma psychologists who have collectively spent nearly 60 years investigating and treating the devastating effects of violation and assault, we have concrete suggestions based on clinical experience and research for such change.

People have been talking for years about the need for the Catholic Church to treat survivors of clerical sexual abuse with respect and dignity, to remove perpetrating priests, and to have real accountability for bishops who facilitated and enabled the abuse. But, when the key Catholic bishops gather for their February meeting, they need to address the dark cloud that overhangs the Synod – something called institutional betrayal.

Wrongdoings perpetrated by an institution upon which individuals are dependent can be as devastating as familial abuse. Up until now, the Catholic Church’s failure to prevent sexual assault or respond supportively to survivors has been a tremendous violation of trust and confidence, and produced fountains of reverberating harm.

Because institutional betrayal is so serious and its effects so deep, something called institutional courage will be needed to put into place tangible turnarounds for meaningful correction and future prevention.

Trauma on a different level

Research on betrayal trauma can help to illustrate the damage the Church has done. Betrayal trauma, or trauma perpetrated by trusted people, such as familial rape, childhood abuse perpetrated by a caregiver and domestic violence, are especially toxic. The brain appears to remember and process betrayal trauma differently than other traumas. Likely the impact on the heart and soul is different as well. When a victim is dependent upon a perpetrator for survival and sustenance, the foundation of their very existence is at stake. Everything they believe about themselves, other people and the world can be unreliable, distorted and harmful, like a carnival fun-house mirror. Except there is no walking away, no easy escape and no validation that the images are warped.

People, especially children, can trust and depend upon institutions in much the same way that people depend on family. For many members of the flock, the Catholic Church was not only a place of worship and community, but a source of safety and spiritual growth.

A growing body of psychological science has examined the role of institutions in traumatic experiences. When sexual abuse survivors are met with denial, harassment and insensitive investigative practices, this is institutional betrayal. There is no doubt that the Church is guilty in taking action to harm its members, such as knowingly hiring clergy with abuse allegations, as well as failing to take action to protect, such as not acting on reports of abuse.

Institutional betrayal has been linked to physical and mental health problems in survivors. For example, experiences of institutional betrayal are associated with post-traumatic stress and depression, as well as increased odds of attempting suicide. On top of the direct sinister effects of being sexually assaulted by a priest, these institutional betrayals lay an extra thick, sticky coating of shame, disgust, alienation and loss.

Healing the hurts

Beginning in early 2002, The Boston Globe’s investigative team, Spotlight, reported on a pattern of sexual abuse of minors by Catholic clergy and cover-ups by the Catholic Archdiocese of Boston. Over time, shocking, credible allegations poured forth. The world learned these were not isolated incidents. This widespread assault and wrongdoing is clearly systemic in nature. And, this doesn’t just happen in the U.S., but in other countries as well.

It’s 2019. The sexual abuse and cover-up in the Catholic Church have not stopped. In fact, it seems to have had a resurgence, at least in its reporting. At least 16 states have begun to seriously examine allegations, issuing subpoenas and outing predation, within their borders. Some Catholics are despondent, losing faith and feeling intense anger. For many, the scars have not healed.

The pope has been an ardent defender of migrants – bringing attention to the difficulty of their plight and the compassion needed for their embrace. The survivors of clerical abuse can be viewed as refugees of sorts. These survivors are without the shelter of their spiritual home, fleeing from past dangers and current, ongoing disbelief and derision. They are in need of assistance and protection, and soothing salve. Many are exhausted from raging a war to be heard and depleted from spiritual famine.

Hosting the February bishops’ conference and meeting with survivors ahead of time is not sufficient. This is a start. But not nearly enough. The answer in our view is institutional courage. The Roman Catholic Church needs to do more than take ownership, institute deserved repercussions to perpetrators, and demand better. More specifically, they need to set and enforce meaningful, substantive, corrective and preventative measures. These include genuine, concrete changes, such as acknowledging wrongdoing, apologizing, correcting and retracting false statements, committing to conduct regular ongoing self-assessments, operating with transparency, and engaging wholeheartedly in a reparation process. An introductory institutional reparations checklist could be followed and made public for the world to see.

Healing from trauma can be complicated, but is possible. While the perpetrator or institutional betrayers’ acknowledgment of the trauma is not often sufficient for healing, apology and restitution can positively impact the recovery process. As part of truly embracing institutional courage, providing meaningful education to all church leaders about betrayal trauma and institutional betrayal is necessary. In addition, it will be crucial to publicly commit funding to each of these steps of institutional courage.

At this upcoming bishop presidents’ meeting in Rome, we pray that Pope Francis stands on the balcony above St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City, with his arms outstretched, calling to his congregation, honoring those who have dared to blow the whistle, and asking for forgiveness. The survivors deserve nothing less than acknowledgment, address and apologies for these horrid individual and institutional betrayals. This is a grand opportunity to repair and prevent continuation of trauma as well as future injustices.

Joan M. Cook, Ph.D. has received grant funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Jennifer J. Freyd, PhD, is a Fellow, 2018-19, at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University. She receives book royalties and honoraria for giving presentations, and she is paid as a consultant on some legal cases and for some organizations.

Read These Next

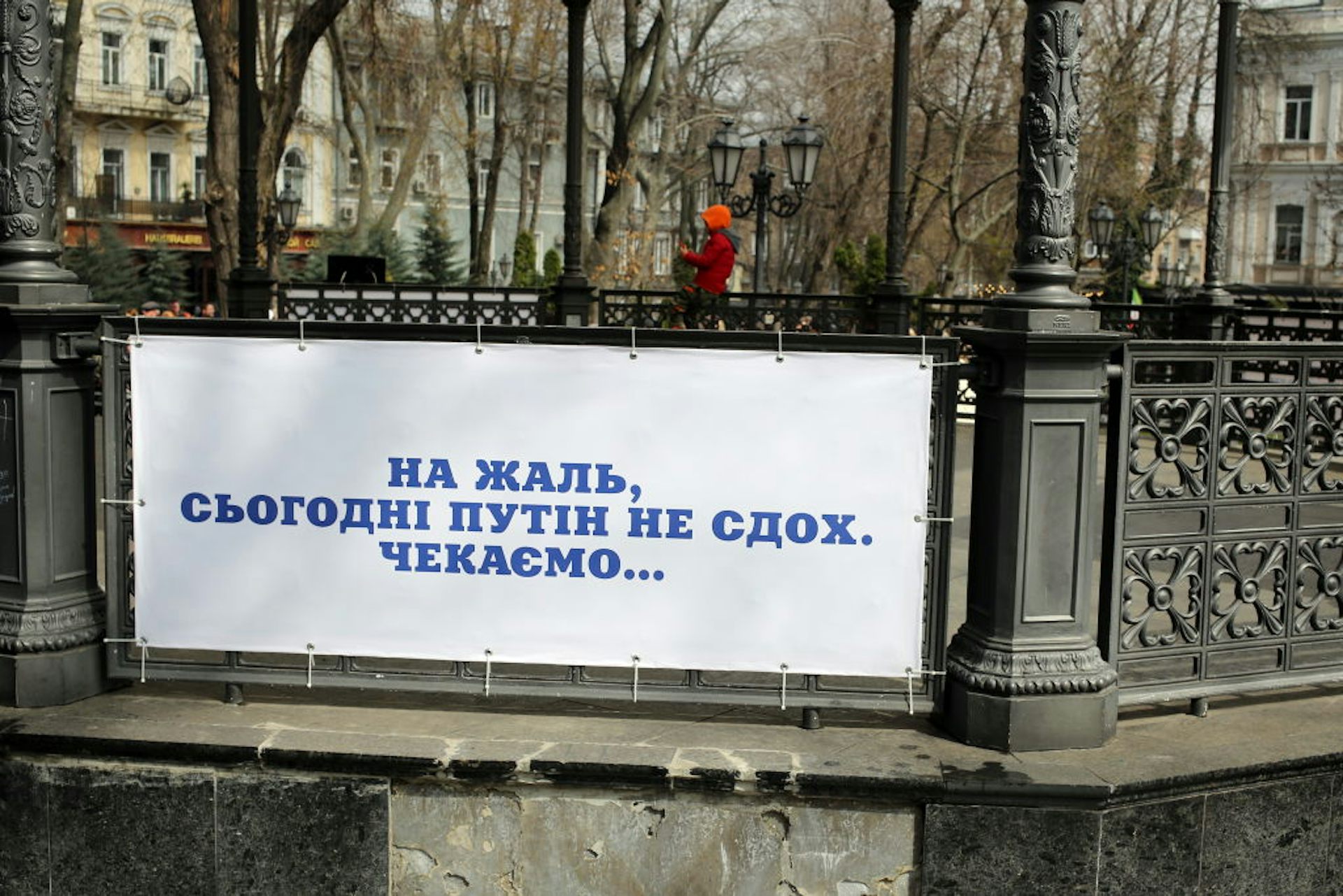

Front lines of humor: Dark humor voices Ukrainians’ hopes for victory

Humor has served many functions since Russia’s full-scale invasion, from providing Ukrainians with…

Iran will respond to US-Israeli strikes as existential threats to the regime – because they are

The latest attack on Iran goes far beyond previous operations by Israel and the US in both scale and…

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…