How childbearing varies across US women in 3 charts

How do women decide how many children to have and when to have them? The data reveal a few major patterns.

Falling U.S. fertility rates have been making headlines.

These reports tend to focus on a single measure: the average number of children that women have, nationally. However, this one number masks large and interesting variation in people’s childbearing behavior.

The National Survey of Family Growth – one of the best sources of information on this topic – released a report in July that points to some of this variation.

It shows that the number of children and the timing of childbearing differ meaningfully across women and across groups, reflecting some of the significant demographic divides in the U.S.

Family size

There’s a lot of variation in family size – but the data show that large families are unusual.

Among women who have recently completed their childbearing, the most common number of children in the national survey was two, followed by three and then one, and then none. Large families are the least common: Only 13 percent of women have four of more children during their lives.

By historical standards, the current dominance of the two-child family is notable. Before now, societies had not converged around a particular number of children to such a large extent. And yet, only about one-third of women have two children – so the majority don’t conform to this standard.

Women may start reporting fewer children on average in upcoming years, as generations who were hit hardest by the Great Recession finish out their childbearing years.

There are also interesting differences by gender. Men were more likely to report lower numbers of children compared to women. This is likely due to men not reporting some children they fathered, particularly those fathered at younger ages.

The first child

The timing of childbearing differs substantially across groups.

Women vary not only in the number of children they have, but also the circumstances surrounding births. Often, this variation takes the form of consistent patterns by characteristics like income, race-ethnicity or geographic location.

One pattern shown in the report is that the timing of first births varies by education level. Women with lower levels of education start childbearing earlier than better-educated women, on average. For example, by age 25, two-thirds of high school-educated women had a first birth, but it takes until age 35 before two-thirds of college-educated women have had a birth.

These statistics also indicate that the likelihood of having no children varies substantially by education level. By age 40, nearly all women without a high school degree had a child. The same was true for only three-quarters of women with a college degree.

Spacing between children

The time between births varies, too.

College-educated women space their births more closely together than less educated women. About 60 percent of college-educated women have their second child within three years of the first one, compared to just half of high school-educated women.

Waiting more than four years between the first and second birth is also more common among less educated women than more educated women.

Why? One factor is likely that college-educated women start childbearing later and therefore have a smaller window of time in which to “fit in” their births.

In addition, it may be that greater relationship stability and lower unintended birth rates mean that highly educated women are more likely to feel they are in a good position to have a second birth shortly after the first.

Caroline Sten Hartnett does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Public defender shortage is leading to hundreds of criminal cases being dismissed

There are never enough lawyers to provide indigent defense, but the situation has gotten worse since…

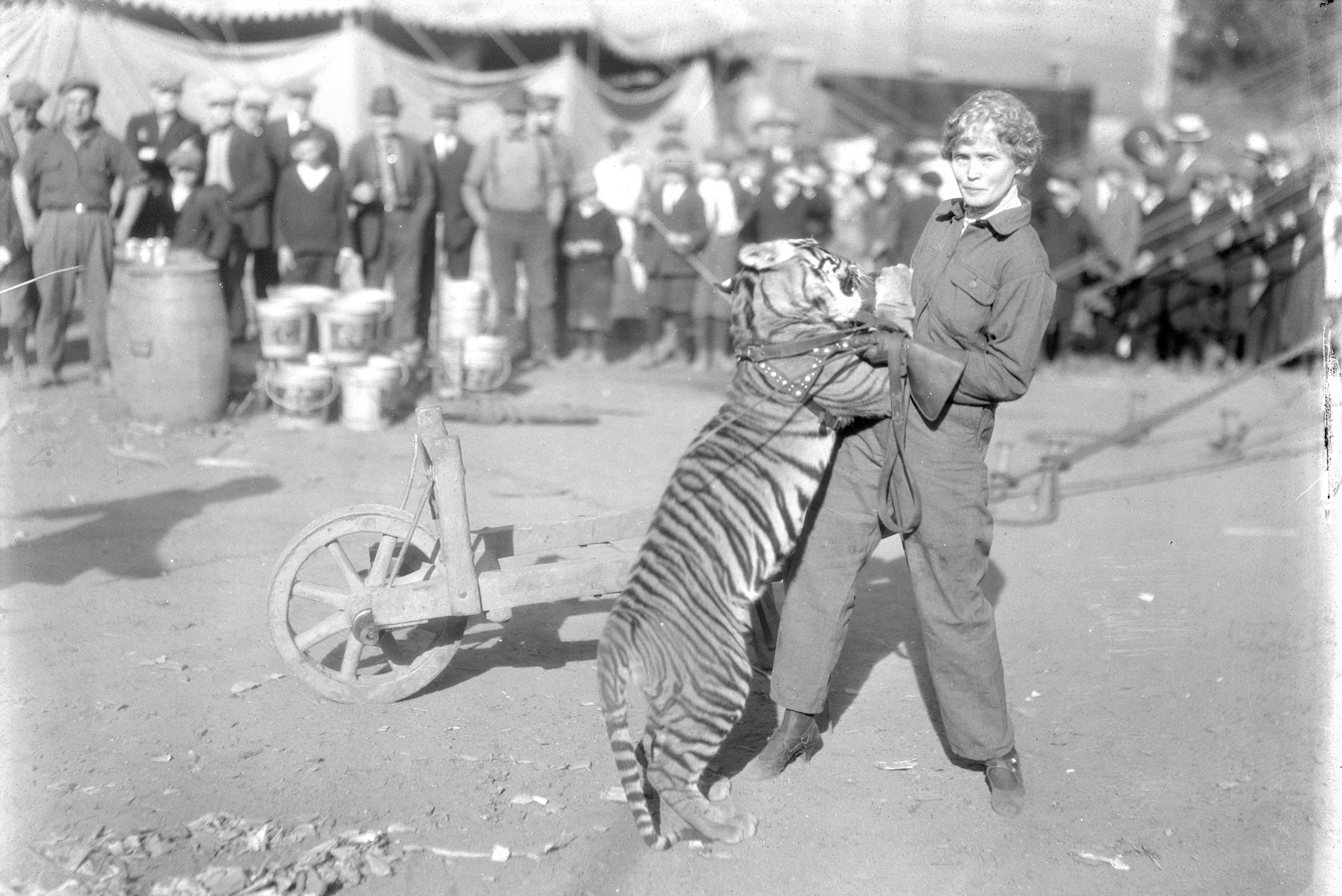

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s killing plays into Shiite Islam’s reverence for martyrs, but not for all Ir

Khamenei was a deeply polarizing figure in Iran – perceived by some as a martyr and others as an oppressor.