How to make meaning in aftermath of Pittsburgh and other violent acts

The deaths of 11 worshippers at the Tree of Life synagogue filled people with sadness and fear. Transforming the grief into meaning is very difficult, a trauma psychologist writes, but ultimately healing.

As the last of the funerals were held for the 11 people gunned down at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, many of the survivors, their loved ones and the world are left with terribly heavy hearts. How do we emotionally digest such hatred and tremendous loss of life? How do we make sense out of something so senseless?

As a trauma psychologist, let me say there is no single formula for recovery from traumatic events. But creating meaning and finding a coherent narrative is often very positive adaptive psychological response.

For many of us, trauma shatters our basic assumptions. The slaughtering of innocent people, be it in a place of worship, a school, a nightclub or a concert, violates our sense that the world is a good and safe place. We wonder how some people in our world have become, not only unhinged, but venomous and vile. In an attempt to make sense out of extremely stressful and traumatic events, some people find that finding or creating meaning or purpose helps them transcend the pain. Meaning-making goes beyond a surface understanding of the facts. It is a concerted attempt to process and resolve violations by restoring a sense that the world is meaningful and life worthwhile. It involves people reappraising their experiences and looking for opportunities to learn and grow. For some, meaning-making is a core coping mechanism, a salve to the aching soul.

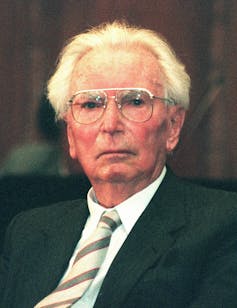

Viktor Frankl’s gift to the world

Dr. Viktor Frankl, an Austrian psychiatrist, was a prisoner in four different German concentration camps, including Auschwitz and Dachau, during World War II. His parents, brother and wife were all killed in the camps. Frankl witnessed people being sent to the crematoriums. He watched fellow prisoners descend from denial to apathy. How did Frankl and others like him work through their traumas and transcend such historic and mass violent loss?

Frankl’s survival strategy in the face of such prolonged and severe trauma was to try to help his fellow prisoners re-establish their own psychological health. In 1946, he wrote a book titled “Man’s Search for Meaning,” describing his concentration camp experiences as well as a new type of therapy.

In this piece of survival literature, Frankl argued that even when an individual is transgressed upon in the most vicious and evil of ways, they must make a choice to search for value and meaning and move forward with renewed purpose. By the time of Frankl’s death in 1997, “Man’s Search for Meaning” had become incredibly influential – having sold more than 10 million copies in 24 languages.

Curbing the pain as best as possible

Extensive research has taken place on the concept of meaning-making after a wide variety of traumatic experiences and stressful events. In an examination of how 133 older adult Holocaust survivors dealt with their trauma, many reported that even while they were still imprisoned, they kept hope alive by believing in liberation, trying to envision the positives the future might hold, and cultivating constructive attitudes, such as gratitude. Post-captivity, these survivors empowered themselves by taking moral stands to fight oppression and hatred where they could.

In general, when a person is successful in meaning-making, he or she often experiences less emotional distress. But, meaning-making takes effort and is multifaceted. And, whether it’s necessary or adaptive depends on a number of factors. The meaning-making process typically occurs in one of three ways: searching for and finding meaning; searching for and never finding meaning; and never searching for meaning.

Many find that trauma puts good things in perspective. For some, it can improve relationships with others and promote religious or spiritual growth. Some even experience a greater appreciation of life and become more aware of their psychological strengths. Others, however, find it impossible to make any meaning of their trauma. Some struggle with wondering “Why me?” or “Why us?” Although this is normal and understandable, if left unresolved, this might actually maintain psychic harm.

Harden not our hearts

It’s no secret that many Americans are feeling frightened that the social fabric that binds and weaves us together is under attack. There is a cost to being unaware of evil, but there is a larger price to hardening our hearts and closing ourselves into a heavily fortified bunker. Social and behavioral science researchers know a lot about how hate happens and why. Developing a psychological, sociocultural, or philosophical explanation or view may help to make it more digestible, or at least a little less personal.

Creating meaning post-trauma is often the product of effort and intention. It is frequently a struggle or a deliberate search and can facilitate multiple positive changes. For example, individuals who offer support to others during a traumatic event also experience lower levels of distress themselves. Their show of compassion also increases their ability to find meaning in the trauma. Moving from dread or numbness toward vital connection with others is important.

Some people find meaning through action - volunteering to get the word out to vote, campaigning for open-hearted political candidates, making donations, joining a civic organization, or engaging in spirituality. Down deep most of us realize that the alternative is to be isolated and alone, excessively fearful and restricted.

Living in a world of violence

It will likely remain hard to bear witness to the kinds of suffering we saw in Pittsburgh, to remind ourselves of good when we see so much evil and hatred. It is likely true that many of us will probably not see an ending to such senseless violence and hate in our lifetimes.

But, I hope we can all tap into Dr. Frankl’s amazing will and strength to endure and find ways to repair, heal, grow and learn. May we forge meaning and closure to this violent loss.

Joan M. Cook has received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, PCORI and the AHRQ.

Read These Next

How Denver’s Northeast Park Hill community reduced youth violence by 75%

A neighborhood coalition identified risk factors for youth violence and prevention strategies.

Researchers are combining drones and AI to make removing land mines faster and safer

Using drones makes detecting land mines safer. Using AI to fuse data from multiple types of sensors…

2025 was hotter than it should have been – 5 influences and a dirty surprise offer clues to what’s a

Solar cycles, sea ice and rising electricity use all play a role. So does an unhealthy surprise that…