Success of immunotherapy stimulates future pigment cell and melanoma research

An international team of researchers is probing the links between skin diseases, including cancer, to speed the search for cures.

Our skin is not only the largest organ and primary contact interface with the world, it also reflects our individuality. From a medical point of view, different skin tones come with different pathological features, and it is no secret that skin color matters in health care.

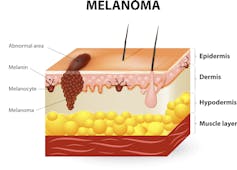

Malignant melanoma, the most deadly skin cancer, has played an important role in understanding immune responses to cancer. One clue about how to attack these aggressive cancers came from a case in which a patient’s melanoma regression was linked to a disease called vitiligo, a patchy loss of pigmentation. Additional insights came from breakthroughs in our understanding of how the immune system fights cancer, which also resulted in the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for James Allison and Tasuku Honjo who pioneered the field of immunotherapy. The connection between melanoma and vitiligo is the pigment-producing skin cell called a melanocyte – when it divides uncontrollably it leads to melanoma, and when it is destroyed it causes vitiligo.

My cancer systems biology research group at the University of California is focused on metabolism and molecular signaling of melanoma. During the past year, in my role as council member of the Pan-American Society for Pigment Cell Research, I had the opportunity to spearhead a team effort to identify the next phase in our battle against skin cancer and pigment disorders. The task force included an international panel of experts from more than 30 cancer centers around the world. Our new research identifies emerging challenges and opportunities in melanoma and pigment cell research.

Even though excellent efficacy and some complete remissions have been seen in a limited number of melanoma patients, some of whom may be regarded as cured of cancer, many malignancies do not respond to immunotherapy. Predicting which patient’s tumor will respond to immunotherapy remains a major challenge and an active field of research.

Following the panel’s assessment, the goal of the research community is to translate the successes of cancer immunotherapy to related topics, including cancer prevention, loss of pigmentation and hyperpigmentation frequently observed following inflammatory processes.

Addressing future needs of a diverse community

One of the aspects the committee addressed was the enormous disparity between the rates of skin cancers between different ethnicities. Traditionally underserved ethnic populations such as Hispanics and African-Americans tend to suffer higher rates of cancer and age-related disease for reasons that are not always clear. Variations in health, lifestyle and socioeconomic risk factors across racial groups may account for some differences. Other differences are found in genes related to pigmentation and metabolism.

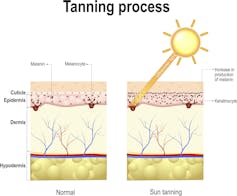

The colored pigment in our skin is produced by special protective cells called melanocytes found within our skin that absorb dangerous UV radiation. On a campus like at the University of California, Merced, which is dedicated to underserved minorities, one encounters an ethnically diverse, young generation in all skin tones.

Hispanics represent the largest and fastest-growing ethnic group in California. They are also 50 percent more likely to suffer from late-stage malignancies as white people of similar age. As such, Hispanic families in the Central Valley of California bear a disproportionately large share of the nation’s substantial and ever-mounting burden of cancer due to environmental exposure to carcinogens. One of the goals of the research community is to figure out why.

Pigment-producing melanocytes protect from UV

The life-threatening form of skin cancer, melanoma, arises when pigment-producing melanocytes undergo cancerous transformation. That happens when the DNA inside these cells accumulate mutations and other damage at locations on the body exposed to UV-intensive sunlight.

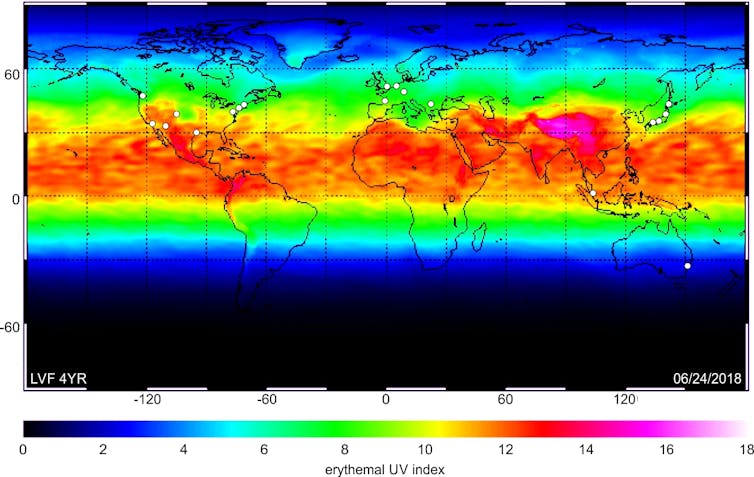

When genetic mutations affect the production of the melanin pigment, people encounter partial or complete loss of pigmentation of their skin, eyes and hair. Albinism is a rare genetically inherited condition, in which cells produce no pigment. In sub-Saharan Africa people with this disease are prone to sunburns and UV-dependent skin cancers, particularly in regions with a high UV index.

In developing countries, people with albinism may not have access to health care specialists, sunscreen or protective clothes. Sadly, patients with albinism in Africa are increasingly targeted for ritual assassinations. The united pigment cell community stands in solidarity and supports patients suffering from albinism, leaving a unique footprint in the field of pigment cell biology.

In some cases, like vitiligo, pigment loss occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks melanocytes and targets them for destruction. In some cases, the disease can be reversed by suppressing the immune system and promoting melanocyte regeneration

At the other end of the spectrum is hyperpigmentation – too much pigmentation – called melasma. Albinism, vitiligo and hyperpigmentation are all disorders where patients show different responses to hormone changes, metabolism or drugs, depending on their gender and skin type.

The future of cancer research is prevention

Now that immunotherapy and genomic insights have led to unprecedented improvement in the overall survival of cancer patients, the next logical step is to prevent cancer from happening in the first place.

Primary prevention and early detection are powerful but underutilized strategies to reduce cancer incidence and mortality. To systematically battle skin cancer mortality, the Melanoma Prevention Working Group that I am part of proposes a state-of-the-art pipeline to translate the most promising chemoprevention agents for high-risk patients into the clinic. A research program and science alliance on precision medicine and cancer prevention aims to reduce exposure of carcinogens and health disparity among underserved minorities. The bilateral project between Germany and the U.S. addresses timely aspects of big data science across international boundaries, health care reforms, bioethical consideration of direct-to-consumer diagnostics and treatment protocols based on our individuality. Important goals of the scientific exchange across continents is to learn about integration, diversity and ways to overcome prejudice or judgment based on the color of skin, which might be approached very differently in different counties.

The future and importance of studying pigment cells is defined most dramatically by recent advances in melanoma immunotherapies that can be lifesaving, but also by the many diseases and conditions intersecting with the pigment system that remain in need of effective treatments.

Ongoing efforts are focused on utilizing the established preclinical models to overcome drug adaptation and immunotherapy resistance as well as precision medicine profiling of cancer patients. The research community expects that genome-wide data in combination with systems biology analyses will identify new drug targets and help overcome therapy-resistant cancers.

Fabian V. Filipp, Assistant Professor of Systems Biology and Cancer Metabolism at the University of California Merced, receives funding from National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, National Science Foundation, European Molecular Biology Organization, and the University of California Cancer Research Coordinating Committee. He is an elected council member of the PanAmerican Society for Pigment Cell Research.

Read These Next

GLP-1 drugs may fight addiction across every major substance, according to a study of 600,000 people

GLP-1 drugs are the first medication to show promise for treating addiction to a wide range of substances.

Hezbollah − degraded, weakened but not yet disarmed − destabilizes Lebanon once again

Hezbollah’s entry into the current war followed the killing of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The group has…

Housing First helps people find permanent homes in Detroit − but HUD plans to divert funds to short-

Detroit’s homelessness response system could lose millions of dollars in federal funding for permanent…