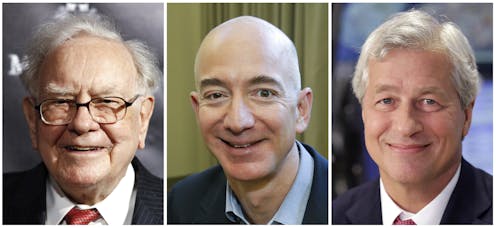

The Bezos-Buffett-Dimon health care venture: Eliminate the middlemen

Noted physician and author Atul Gawande was named CEO of a new health care venture aimed at cutting costs and improving care. But the most important man to keep an eye on in this effort isn't Gawande. It's the middleman.

The new health care venture formed by Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase announced June 20 that Harvard professor and well-known author Atul Gawande would be the company’s CEO. The idea for the new company is to innovate by cutting costs from the health care system, starting with the more than 1 million employees of the three companies behind the venture.

Previous efforts to contain health care spending – from managed care to high deductible health plans to alternative payment models – shared the goal of eliminating unnecessary and overly expensive services. But these practices are very hard to change, since they’re based on physicians’ clinical judgment and patient preferences.

The new joint venture may find it is easier to start with a different question entirely: Can we reduce spending by 15 to 20 percent just by cutting out unnecessary middlemen?

As business school professors, we know that cutting the unnecessary transactions costs generated by unneeded middlemen is the classic first step. We expect it will quickly be seen as the low-hanging fruit for this new organization.

Tackling inefficient health care arrangements

In its main business, Amazon cuts out everyone except the original supplier of what they sell – and the post office. That’s how they have cut prices of other consumer products.

There’s ample room to replicate that success in health care, because the system in the U.S. has long been plagued by excessive transaction costs – the expenses incurred when buying or selling goods and services. These include irrational pricing, as evidenced by the price of services varying wildly for hospitals, insurers and patients. This, along with unnecessarily complicated billing systems, creates the need for extensive bureaucracies to manage all the varied relationships.

Businesses like Amazon try to fix this sort of mess and make shopping for services more convenient and transparent. Imagine an easy-to-use platform where patients can readily assess the price and quality of competing providers and quickly schedule appointments or perhaps even initiate an online consultation. We bet Dr. Gawande is imagining it.

There are also several less visible sources of unnecessary transactions costs that are vulnerable to disruption. Two of these center on pharmacy benefit management companies (PBMs) and insurance brokers and consultants.

Lately, the big pharmaceutical firms have pointed at PBMs to deflect the blame for their sky-high drug prices. President Donald Trump seems to share this view. However, PBMs are just middlemen whose only purpose is to lubricate the relationship between insurers, Big Pharma and pharmacy chains. They let pharmacies know what your plan covers and what you owe – a valuable service worth a nominal payment.

But PBMs also work the system by collecting rebates of up to 25 percent from drug manufacturers as an agent for insurers. They then pass some, but not all, of them on to the insurance companies and their customers. We believe these rebates should be understood for what they really are: bribes that Big Pharma pays in an attempt to bias insurers to favor their higher-priced products over others.

Health insurers, such as the plan one of us ran as CEO, receive these higher rebates based on volume – but only for drugs with a competitive alternative where there is a choice of what to cover. The growth of drug rebates clearly indicates these bribes work independent of clinical appropriateness and input from doctors.

Furthermore, Big Pharma’s use of coupons and donations to reduce what patients pay permits huge increases in drug prices, which more than offsets these rebates. The patient is insulated from higher prices at the pharmacy but still ultimately pays more. The cost of these coupons and donations shifts to the insurer, and the insurer then gets it back in premium hikes. This whole mess rests on rebates as an unproductive transaction cost that has little real reason to exist at all.

Insurers are not blameless. They also try to buy business, creating unnecessary transaction costs in the process. For instance, employers typically hire brokers and consultants to advise them on coverage for their employees. Given the complexity of insurance plans, seeking such help is usually a rational decision. But the hidden fact is that these middlemen, in addition to fees from their clients, are taking side payments from insurers up to 16 percent of the premium – clearly designed to bias their recommendations to employers. These payments are another case of unproductive transactions costs that can be eliminated by bargaining directly with insurers and drug companies.

More targets for the joint venture

Efforts to remove the middlemen won’t stop with PBMs and brokers. Insurers, the biggest middlemen, are certainly vulnerable with their high administrative costs ranging from 12 percent to 18 percent. And this new joint venture might also ask why they would pay wildly variable prices for similar health care services when they can dictate package prices for a given episode of care and channel employees to higher-quality providers willing to bargain. Employers like these three can even hire their own clinicians and save another layer of overhead. And if they can do it for their own employees, they can share these efficiencies with others.

Ron Coase, who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1991, demonstrated that industries are organized ultimately to minimize transactions costs. This is obvious in the history of other sectors where fragmented producers gradually transformed into integrated organizations, and then into assemblers as labor and transportation costs changed. In a similar way, the internet has allowed radical restructuring of many businesses as transaction costs have fallen.

So far, the health care system has largely avoided such transformations. The Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase venture suggests their time is coming.

J.B. Silvers is affiliated with Case Western Reserve University and MetroHealth System.

Mark Vortuba does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Billions of dollars, decades of progress spent eliminating devastating diseases may be lost with und

Public health campaigns had made significant strides toward eradicating diseases like elephantitis and…

Operational secrecy kept the US from making evacuation plans – and that means Americans in the Midea

A longtime diplomat explains how the State Department normally encourages and helps Americans to leave…

How Denver’s Northeast Park Hill community reduced youth violence by 75%

A neighborhood coalition identified risk factors for youth violence and prevention strategies.