US fertility is dropping. Here's why some experts saw it coming

The number of births in the US is down 2 percent. That pops the country's 'fertility bubble' – and brings numbers closer in line with peer countries.

The Centers for Disease Control reported this month that the number of births in the U.S. is down 2 percent – “the lowest number in 30 years.”

These reports were met with surprise and alarm. ScienceAlert, for example, led with the headline “U.S. Fertility Rates Have Plummeted Into Uncharted Territory, and Nobody Knows Why.”

However, this recent decline fits with global trends and isn’t unprecedented in U.S. history. As a demographer who studies fertility trends, what strikes me as anomalous is not the recent drop, but the previous high fertility “bubble.”

Unusually high rates

The U.S. maintained surprisingly high fertility rates for a long time.

After the baby boom of the 1950s and 1960s, fertility in the U.S. and other wealthy countries fell during the 1970s. However, the U.S. steadily rebounded, even as rates in most other wealthy countries stayed low or fell even lower.

By 1990, there were 2.1 children per woman in the U.S., compared to 1.4 in Spain and 1.5 in Germany, for example.

This gap between the U.S. and other developed countries baffled demographers through the 1990s and early 2000s. Public policy choices couldn’t explain it. The U.S. maintained its high fertility rate even while being comparatively weak on “pro-fertility” policies like family leave and financial support for parents.

Several factors propped up the fertility rate. The U.S. had a steady flow of immigrants from higher-fertility countries. It also had a persistently high unintended pregnancy rate; a flexible labor market that allowed parents to exit and re-enter the workforce; and a strong, stable economy.

Catching up with others

The recent drop in fertility brings the U.S. more in line with peer countries.

In 2017, the U.S. dropped to 1.76 children per woman. This number is well within the range of similar countries, and even remains toward the top of the pack. Only a few wealthy countries – including France, Australia and Sweden – have higher fertility rates than the U.S., and differences are small.

But depending on how you measure it, fertility in the U.S. is not at a historic low. By one measure, called the “general fertility rate,” U.S. fertility is indeed the lowest it’s ever been. This is the measure widely cited in media reports.

But, in my view, this measure is flawed, because variations in the age structure of women can artificially inflate or depress it. For example, having a high proportion of women in their late 20s will inflate the rate.

A better measure, without this issue, is total fertility rate. Using this superior measure, the U.S. rate in 2017 was higher than in 1976 and equal to fertility rate in 1978. So, the country has been here before.

Fluctuation is normal

It’s normal for fertility rates in wealthy countries to go up and down. People tend to adjust the timing of births to take advantage of a “good” year – such as one when high state benefits are offered – or avoid a “bad” year – such as one with high economic uncertainty.

Spain’s fertility declined from the 1970s to the early 1990s, as women increasingly joined the labor market but husbands didn’t share the load at home. (Perhaps working and taking care of three kids was more than most women wanted to handle.)

In Russia, fertility fell steadily following the economic and political shock of the collapse of the Soviet Union. It later climbed back.

And, between the 1990s and early 2000s, Sweden’s fertility fell and then rose, in part due to changes in the timing of births, the economy, and the state’s generous supports for parents.

There are a number of possible explanations for the recent dip in U.S. The Great Recession is certainly important, and its effects linger even as the economy has recovered. A Gallup poll indicates that, for the past several years, Americans’ “satisfaction with the way things are going in the U.S.” has remained substantially below levels in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

In addition, declines in fertility rates have been particularly steep among younger people, who are disproportionately affected by high student loan debt and may find it harder than previous generations to get on their feet economically. However, if economic conditions improve for these young people, research suggests they are likely to “make up” many of these births later in their lives.

Finally, part of the drop in overall fertility is due to declines in unintended and adolescent birth rates. Such declines have been a public policy goal for decades — so the dip in fertility should be seen as a good thing, not a cause for gloom.

Keep it steady

The fertility rate in the U.S. isn’t alarming, yet. But a continued drop could cause problems.

There are at least two scenarios to worry about. The first is a persistently low fertility rate that leads, over time, to a shrinking population. A population with a sustained fertility rate of 1.3 children per woman, for example, will quickly contract.

The second is a large, rapid fall in fertility. That eventually creates a lopsided population with more old than young people – making it hard, for example, to sustain policies like social security.

Both of these scenarios could happen, but it’s important to emphasize that the U.S. is not currently experiencing either one. However, it might be wise for the government to consider implementing stronger pro-family public policies such as paid family leave and subsidized child care. The U.S. is unlikely to return to the exceptionally high fertility rates enjoyed before the last recession, but the current rate is one that many countries would be thrilled with.

Caroline Sten Hartnett does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Trauma patients recover faster when medical teams know each other well, new study finds

A new study from a Pittsburgh hospital finds that trauma patients recover faster when emergency medical…

Brazilian jiu-jitsu is having its #MeToo moment

With legend Andre Galvao accused of sexual misconduct, gyms and athletes have been forced to confront…

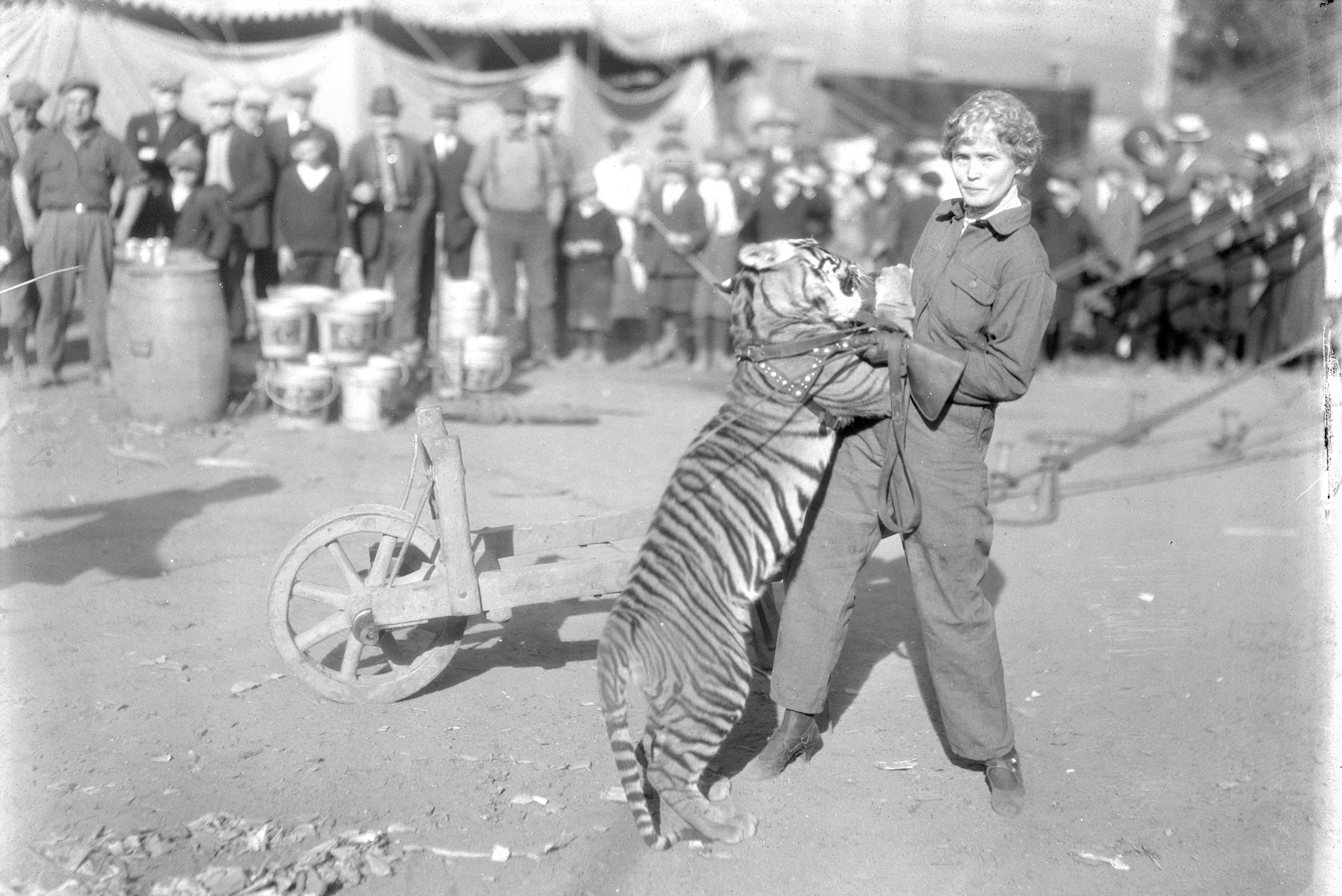

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.