How live liver transplants could save thousands of lives

April is National Donate Life Month, a time to emphasize the importance of organ donation. It is also a good time to learn about a major medical advance that allows liver transplants from living donors.

The success of liver transplantation represents one of the great miracles of modern medicine. Essentially an experimental procedure 35 years ago, it now represents the only definitive method to cure most patients with end-stage liver failure.

The major problem with liver transplantation now is not rejection or infections but rather that there are not enough livers for all the people who need them. Over 14,000 people are waiting for a liver transplant in the United States, but only about 8,000 transplants are done annually. The average waiting time for most patients measures in years – if they receive one at all. One in five patients dies on the waiting list, a number that could be significantly decreased with liver donations from living donors.

I am the clinical director of the Starzl Transplant Institute, named for University of Pittsburgh surgeon and professor Thomas Starzl, who pioneered liver transplantation. I have been involved in transplantation for over 20 years and have been witness to many advances in the field, including the development of live donor liver transplants, that have ultimately allowed thousands of lives to be saved. The medical community could perform a lot more liver transplants in the U.S. if we followed the lead of using livers from live donors, as do many countries.

A vital organ, a scarce resource

More than a hundred different things can lead to liver failure, which can occur at any age, even in newborns. Viral hepatitis, autoimmune disorders, fatty liver disease and alcohol use are just some of them.

Regardless of the cause, in almost all circumstances, a liver transplant can be lifesaving. But the number of patients who need a transplant exceeds the number of available livers from deceased donors. This has resulted in a long wait time for most patients. Many die while waiting.

There are two other problems with having a long waiting list. First, patients must get very sick to reach the top of the waiting list; being very sick is what determines priority on the list. This is not the ideal time to perform a difficult operation, as the patient may be in a debilitated state and have a more difficult, prolonged recovery time. A better strategy would be to perform the transplant when the patient is less ill.

Second, because the organ is a limited resource, only patients with the best potential outcomes are eligible to receive a liver transplant. That means that many patients who could derive a significant survival benefit from liver transplantation are not even placed on a waiting list, as the possibility of getting a transplant from a deceased donor is too low.

A major step forward

While most livers for transplant in the U.S. come from deceased donors, a major advance has occurred in recent years. It now is possible for a surgeon to take a portion of a liver from an otherwise healthy individual and use that for transplant. The procedure started first in children, with the first U.S. transplant in 1989. It then expanded for use in adults by 1996. The availability of a living donor obviates the need for someone to wait, and, therefore, potentially limits the likelihood a person will die while waiting for a liver.

Live liver transplantation allows patients to receive a transplant from a living donor as soon as they are deemed ready for a transplant. This is often a point sooner in the disease process, when they are healthier and better able to tolerate the procedure. This leads to a quicker and less complicated recovery. Additionally, patients who are not eligible for a transplant from a deceased donor can still receive a transplant from a living donor if there is a survival benefit.

Widely used in other countries, but not US

Despite the advantages, living donor liver transplants in the U.S. account for less than 5 percent of all liver transplants. In other countries, such as Korea, Japan and India, living donor liver transplants account for almost 90 percent of liver transplants.

The main reason for the underutilization is a lack of awareness of the procedure, both by patients and the health care community. At UPMC, we strongly believe in the ability of living donor liver transplant to be a lifesaving procedure and offer this as a first-line option to all our patients in need of a liver transplant.

We perform the most living donor liver transplants in the country, and for the first time ever, in 2017, performed more transplants from living than deceased donors.

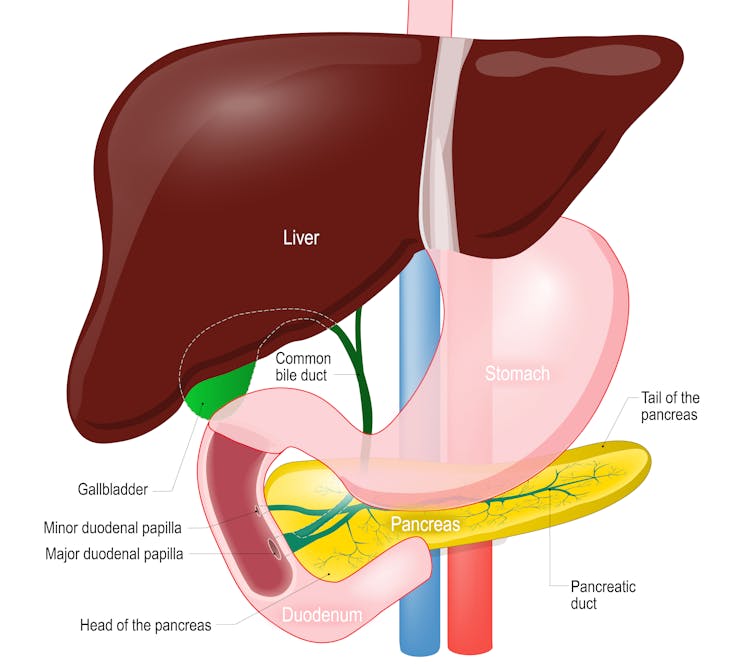

The surgical procedure involves removing a certain portion of a healthy person’s liver (25 percent if the recipient is a child, 40 to 60 percent for adult recipients). This is possible in the liver because of two special properties. First, redundancy is built into our livers, such that only 25 to 30 percent of a normal liver is needed to maintain liver function. Second, the liver has the unique ability to regenerate and regrow to its original size, usually in about eight to 10 weeks.

Proper donor selection is a critical step. Essentially, anyone who is healthy and has a normal liver can potentially be a donor. While potential donors are often related to the recipient, this is not a requirement. Even a stranger can be a donor, so long as he or she is healthy and between 18 and 55.

Our program requires that donors undergo a strict medical and psychosocial evaluation to see if they qualify. A key component is to make sure that the donation is completely voluntary, and that the donor is not being coerced.

Risks to know about

While a living donor liver transplant has many advantages, there are also some disadvantages. The main one is the risk to the donor, who does not benefit physically from the surgery and who faces some risk from surgery. The risk of donor mortality is low, in the range of 0.2 percent. Of over 6,000 procedures done in the U.S. over the last 25 years, six early donor deaths have been reported.

The risk for a complication in the donor after surgery is about 30 percent, though many of the complications are minor. The risk of a major complication, or anything that requires another intervention to fix or has long-term consequences, is closer to 10 percent.

Kidney transplantation from a living donor has been widely accepted for over 50 years. While the risks to the kidney donor versus the liver donor are fewer, they are not zero.

Nonetheless, liver donation represents major surgery, a fact that should be made clear to all donors. Most donors are in the hospital for about five to seven days after surgery and back to their pre-donation health status in about three months.

For the recipient, the surgical procedure is similar to a transplant from a deceased donor, though with some technical differences. Since only a portion of the liver is transplanted, the surgical aspects of the procedure, including the blood vessel and bile duct connections, tend to be more technically challenging. As a result, the literature generally reports a higher incidence of vascular and biliary complications with live versus deceased donor liver transplants.

Our own data at UPMC, however, show no major differences in technical complications between the two types of transplants. Other outcome measures, such as length of stay in the hospital, time to full recovery and survival at one year post-transplant, are all better with live donor transplants. In large part, this is because patients receiving a living donor transplant are healthier going into the surgery.

The bottom line is that living donor liver transplant represents a lifesaving option for all patients with liver failure, offering numerous advantages over the option of waiting for a deceased donor. In my view, all patients in need of a liver transplant should be made aware of this procedure and, in almost every case, be offered a transplant from a live donor as the first option. With this change, many more lives could be saved every year.

Abhi Humar does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

GLP-1 drugs may fight addiction across every major substance, according to a study of 600,000 people

GLP-1 drugs are the first medication to show promise for treating addiction to a wide range of substances.

Hezbollah − degraded, weakened but not yet disarmed − destabilizes Lebanon once again

Hezbollah’s entry into the current war followed the killing of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The group has…

Housing First helps people find permanent homes in Detroit − but HUD plans to divert funds to short-

Detroit’s homelessness response system could lose millions of dollars in federal funding for permanent…