RFK Jr. guts the US childhood vaccine schedule despite its decades-long safety record

In an unprecedented move, health officials cut the number of vaccines routinely recommended for children from 17 to 11.

The Trump administration’s overhauling of the decades-old childhood vaccination schedule, announced by federal health officials on Jan. 5, 2026, has raised alarm among public health experts and pediatricians.

The U.S. childhood immunization schedule, the grid of colored bars pediatricians share with parents, recommends a set of vaccines given from birth through adolescence to prevent a range of serious infections. The basic structure has been in place since 1995, when federal health officials and medical organizations first issued a unified national standard, though new vaccines have been added regularly as science advanced.

That schedule is now being dismantled.

In all, the sweeping change reduces the universally recommended childhood vaccines from 17 to 11. It moves vaccines against rotavirus, influenza, hepatitis A, hepatitis B and meningococcal disease from routine recommendations to “shared clinical decision-making,” a category that shifts responsibility for initiating vaccination from the health care system to individual families.

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has cast doubt on vaccine safety for decades, justified these changes by citing a 33-page assessment comparing the U.S. schedule to Denmark’s.

But the two countries differ in important ways. Denmark has 6 million people, universal health care and a national registry that tracks every patient. In contrast, the U.S. has 330 million people, 27 million uninsured and a system where millions move between providers.

These changes follow the CDC’s decision in December 2025 to drop a long-held recommendation that all newborns be vaccinated against hepatitis B, despite no new evidence that questions the vaccine’s long-standing safety record.

I’m an infectious disease physician who treats vaccine-preventable diseases and reviews the clinical trial evidence behind immunization recommendations. The vaccine schedule wasn’t designed in a single stroke. It was built gradually over decades, shaped by disease outbreaks, technological breakthroughs and hard-won lessons about reducing childhood illness and death.

The early years

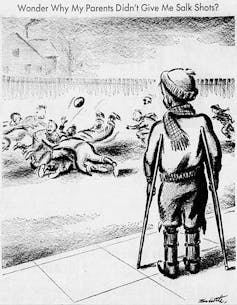

For the first half of the 20th century, most states required that students be vaccinated against smallpox to enter the public school system. But there was no unified national schedule. The combination vaccine against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis, known as the DTP vaccine, emerged in 1948, and the Salk polio vaccine arrived in 1955, but recommendations for when and how to give them varied by state, by physician and even by neighborhood.

The federal government stepped in after tragedy struck. In 1955, a manufacturing failure at Cutter Laboratories in Berkeley, California, produced batches of polio vaccine containing live virus, causing paralysis in dozens of children. The incident made clear that vaccination couldn’t remain a patchwork affair. It required federal oversight.

In 1964, the U.S. surgeon general established the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, to provide expert guidance and recommendations to the CDC on vaccine use. For the first time, a single body would evaluate the evidence and issue national recommendations.

New viral vaccines

Through the 1960s, vaccines against measles (1963), mumps (1967) and rubella (1969) were licensed and eventually combined into what’s known as the MMR shot in 1971. Each addition followed a similar pattern: a disease that killed or disabled thousands of children annually, a vaccine that proved safe and effective in trials, and a recommendation that transformed a seemingly inevitable childhood illness into something preventable.

The rubella vaccine went beyond protecting the children who received it. Rubella, also called German measles, is mild in children but devastating to fetuses, causing deafness, heart defects and intellectual disabilities when pregnant women are infected.

A rubella epidemic in 1964 and 1965 drove this point home: 12.5 million infections and 20,000 cases of congenital rubella syndrome left thousands of children deaf or blind. Vaccinating children also helped protect pregnant women by curbing the spread of infection. By 2015, rubella had been eliminated from the Americas.

Hepatitis B and the safety net

In 1991, the CDC added hepatitis B vaccination at birth to the schedule. Before then, around 18,000 children every year contracted the virus before their 10th birthday.

Many parents wonder why newborns need this vaccine. The answer lies in biology and the limitations of screening.

An adult who contracts hepatitis B has a 95% chance of clearing the virus. An infant infected in the first months of life has a 90% chance of developing chronic infection, and 1 in 4 will eventually die from liver failure or cancer. Infants can acquire the virus from their mothers during birth, from infected household members or through casual contact in child care settings. The virus survives on surfaces for days and is highly contagious.

Early strategies that targeted only high-risk groups failed because screening missed too many infected mothers. Even today, roughly 12% to 18% of pregnant women in the U.S. are never screened for hepatitis B. Until ACIP dropped the recommendation in early December 2025, a first dose of this vaccine at birth served as a safety net, protecting all infants regardless of whether their mothers’ infection status was accurately known.

This safety net worked: Hepatitis B infections in American children fell by 99%.

A unified standard

For decades, different medical organizations issued their own, sometimes conflicting, recommendations. In 1995, ACIP, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians jointly released the first unified childhood immunization schedule, the ancestor of today’s familiar grid. For the first time, parents and physicians had a single national standard.

The schedule continued to evolve. ACIP recommended vaccinations for chickenpox in 1996; rotavirus in 2006, replacing an earlier version withdrawn after safety monitoring detected a rare side effect; and HPV, also in 2006.

Each addition followed the same rigorous process: evidence review, risk-benefit analysis and a public vote by the advisory committee.

More vaccines, less burden

Vaccine skeptics, including Kennedy, often claim erroneously that children’s immune systems are overloaded because the number of vaccines they receive has increased. This argument is routinely marshaled to argue for a reduced childhood vaccination schedule.

One fact often surprises parents: Despite the increase in recommended vaccines, the number of immune-stimulating molecules in those vaccines, called antigens, has dropped dramatically since the 1980s, which means they are less demanding on a child’s immune system.

The whole-cell pertussis vaccine used in the 1980s alone contained roughly 3,000 antigens. Today’s entire schedule contains fewer than 160 antigens, thanks to advances in vaccine technology that allow precise targeting of only the components needed for protection.

What lies ahead

For decades, ACIP recommended changes to the childhood schedule only when new evidence or clear shifts in disease risk demanded it. The Jan. 5 announcement represents a fundamental break from that norm: Multiple vaccines moved out of routine recommendations simultaneously, justified not by new safety data but by comparison to a country with a fundamentally different health care system.

Kennedy accomplished this by filling positions involved in vaccine safety with political appointees. His hand-picked ACIP is stacked with members with a history of anti-vaccine views. The authors of the assessment justifying the change, senior officials at the Food and Drug Administration and at HHS, are both long-time critics of the existing vaccine schedule. The acting CDC director who signed the decision memo is an investor with no clinical or scientific background.

The practical effect will be felt in clinics across the country. Routine recommendations trigger automatic prompts in medical records and enable nurses to vaccinate under standing orders. “Shared clinical decision-making” requires a physician to be involved in every vaccination decision, creating bottlenecks that will inevitably reduce uptake, particularly for the more than 100 million Americans who lack regular access to primary care.

Major medical organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have said that they will continue recommending the full complement of childhood vaccines. Several states, including California, New York and Illinois, will follow established guidelines rather than the new federal recommendations, creating a patchwork where children’s protection depends on where they live.

Portions of this article originally appeared in a previous article published on Dec. 18, 2025.

Jake Scott does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Indie coffee shops are meant to counter corporate behemoths like Starbucks – so why do they all look

The purportedly unique and local feel of coffee shops has instead been homogenized into a singular,…

Fat cells burn energy to make heat – making them the next frontier of weight loss therapies

GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy aid in weight loss by suppressing appetite. Researchers are looking…

Oil isn’t just fuel: Iran conflict could disrupt markets for everything from plastics to fertilizers

Petrochemicals derived from oil and fossil fuels underlie the production of many consumer goods −…