The #iwasfifteen hashtag and ongoing Epstein coverage show how traffickers exploit the vulnerabiliti

The conversation around #iwasfifteen sheds light on the dynamics of abusive relationships and the experiences of trafficking victims.

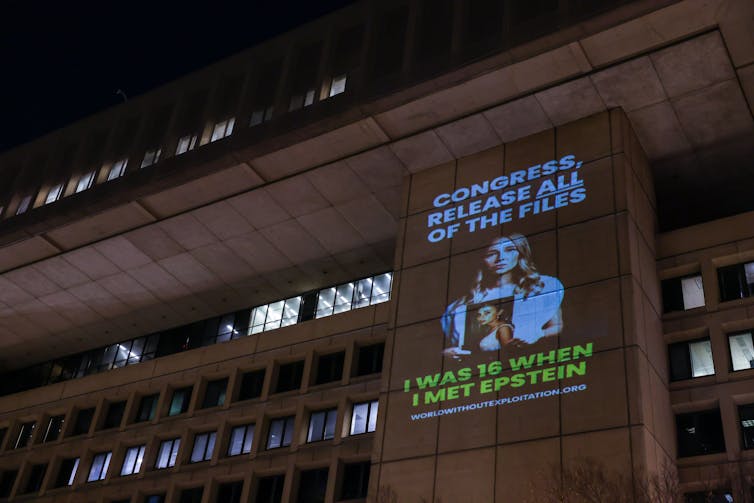

The release of information about the powerful cadre of men associated with convicted sex offender and accused sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein – known as the Epstein files – has been a long time coming.

Under the Epstein Files Transparency Act, which President Donald Trump signed into law in November 2025, the Justice Department must release its documents related to Epstein by Dec. 19, 2025.

But information has been trickling out for months, including more than 20,000 of Epstein’s emails released by members of Congress in November.

In the firestorm of reactions that followed, conservative media figure Megyn Kelly made comments that minimized the victimization of teenagers.

In response to her remarks, a new hashtag, #iwasfifteen, went viral, as celebrities and others took to social media to share photos of themselves as teenagers.

I’m a clinical psychologist who studies intimate violence – from child abuse to domestic violence and sexual assault. After more than two decades in this field, I wasn’t surprised to hear someone minimize the abuse of adolescents. My research and the work of other researchers across the country have shown that victims who disclose their abuse are often met with disbelief and blame.

What did surprise me was how the viral #iwasfifteen hashtag shed light on the dynamics of abuse, pointing to the vulnerabilities that traffickers exploit and the harms they cause.

Abusive tactics in sex trafficking of minors

Unlike stereotypes of teens being kidnapped out of parking lots, people who traffic minors use a range of tactics and build relationships with the teens and tweens they’re targeting. Getting young people to trust and depend on the traffickers is part of entrapping them.

One in-depth 2014 analysis revealed these strategies in action. Researchers looked at more than 40 social service case files of minors who were trafficked and interviewed social service workers.

The researchers found it was common for traffickers to use flattery or romance to entrap adolescents. Some built trust with the teens by helping them out of difficult situations. Meanwhile, the traffickers normalized sex and prostitution as they isolated their victims from their friends and family – all of which echoes the grooming described by victims of Epstein and his accomplice Ghislaine Maxwell.

The research also showed that traffickers kept tight control over the teens, using economic and emotional manipulation. They took their money, blackmailed and shamed them, and threatened harm if they were to leave. As in the Epstein case, many traffickers compelled victims to take part in the trafficking itself, such as by recruiting their friends.

The same kinds of manipulation show up in other studies nationally. A 2019 study found that across more than 1,400 cases, a third of traffickers used threats and psychological coercion to control victims.

Another research team looked across 23 studies of minors who were sex trafficked in the United States and Canada. They found that the youth, who were mostly girls, were entrapped by traffickers who pretended to love or care for them, only to manipulate and abuse them.

The tactics identified by researchers and the reports of how Epstein trapped victims on his island reveal that all the strategies used by traffickers have one thing in common: They create ever more dependence of the victim on the trafficker.

Dependence and betrayal

Adolescence is a time of rapid change – change that traffickers exploit. From the tween through the teen years, young people are forming their identities and learning about romantic relationships, all while their brains are still developing.

During this period of rapid change, they are starting to differentiate and seek autonomy. Yet they remain dependent on the adults in their lives for everything from their psychological needs, such as love, to basic physical needs, such as food and housing.

When victims of trafficking depend – financially, psychologically or physically – on the very person abusing them, it’s a betrayal trauma. In these scenarios, victims depend on the abuser, so they cannot simply leave the situation. Instead, they have to adapt psychologically.

One way to adapt is to minimize awareness of the abuse – or what psychologists call betrayal blindness. In the short term, minimizing awareness of the abuse helps the victim endure the abuse. This could be the difference between life and death for a victim whose abuser might harm them if they try to leave or report the abuse – or for a teen who doesn’t have anywhere else to turn for basic survival.

In the long term, though, betrayal traumas are linked with a host of harms that may affect how victims see themselves and the world around them. Compared with other kinds of traumas, betrayal traumas are linked to more severe psychological and physical health problems.

Betrayal trauma often leads to shame, self-blame and fear and can leave survivors alienated from and distrusting of others. Survivors may also be less likely to disclose abuse perpetrated by someone they trusted. They may even have difficulty remembering what happened to them, which can worsen self-doubt and self-blame.

Making sense of the far-reaching impacts of betrayal trauma can be difficult for survivors – and others who hear their stories later.

Myths and public opinion of victims

When sex traffickers target minors, they use strategies that give others reason to doubt victims. Most people are regularly exposed to misinformation about sexual violence and trafficking through popular media, and that misinformation plays in the perpetrators’ favor.

Researchers started documenting myths about intimate violence decades ago. Since then, research shows that erroneous views of rape, child abuse and sex trafficking persist in media – with consequences for victims.

These myths and misconceptions often seep into the conversation unnoticed, such as when even well-intentioned reporting refers to the girls trafficked by Epstein as “underaged women.” But calling tweens and teens “women” minimizes the age difference with the perpetrators. It also masks the vulnerability of children and adolescents who were victimized by adults.

Myths can include beliefs that intimate violence is rare and always physically violent, and that victims all respond the same way. Myths also tend to minimize the perpetrator’s role while shifting blame to victims for what was done to them, particularly if victims had mental health problems or used substances.

Changing the conversation

With so many myths out there, #iwasfifteen showed one way to change the usual conversation from blaming victims to exposing the ways that abusers exploit tweens and teens. Meeting myths about sex trafficking with research is crucial to putting responsibility where it belongs, on those who traffic youth and perpetrate abuse.

Research shows that the more people buy into myths, the more likely they are to blame victims or not believe them in the first place, including in sex trafficking.

And it’s not only the unsuspecting public that falls for this misinformation. When victims don’t conform to common myths, even law enforcement officers, who are trained to investigate intimate violence, are less likely to believe them.

In this way, the psychological consequences of betrayal trauma – from minimizing the abuse to psychological distress – can feed into myths that people have about intimate violence. Suddenly, it’s easier for friends, family, juries and others to blame victims or not believe them at all.

And, of course, that’s what perpetrators have often told victims all along: No one will believe you. It’s not surprising, then, that victims may take years to come forward, if ever.

Anne P. DePrince has received funding from the Department of Justice, National Institutes of Health, State of Colorado, and University of Denver. She has received honoraria for giving presentations and has been paid as a consultant. She has a book with Oxford University Press. She is an Advisory Group Member of the National Crime Victim Law Institute and a Senior Advisor to the Center for Institutional Courage.

Read These Next

Crowdfunded generosity isn’t taxable – but IRS regulations haven’t kept up with the growth of mutual

Some Americans are discovering that monetary help they received from friends, neighbors or even strangers…

Picky eating starts in the womb – a nutritional neuroscientist explains how to expand your child’s p

While genes do influence some food preferences, positive experiences can help make new tastes easier…

Algorithms that customize marketing to your phone could also influence your views on warfare

AI systems are getting good at optimizing persuasion in commerce. They are also quietly becoming tools…