Gay Men’s Health Crisis showed how everyday people stepped up when institutions failed during the he

Despite funding cuts, political scapegoating and internal tensions, thousands of volunteers came together in the 1980s to provide care to a stigmatized community.

The story of the AIDS movement is one of regular people: students, bartenders, stay-at-home mothers, teachers, retired lawyers, immigrants, Catholic nuns, newly out gay men who had just arrived in New York, and many others. Some had lost friends or lovers. Some felt a moral calling. Some were just trying to balance their sexual karma. Many were angry. Most had no medical background or professional credentials – just a sense of urgency, tenacity and an unwillingness to look away.

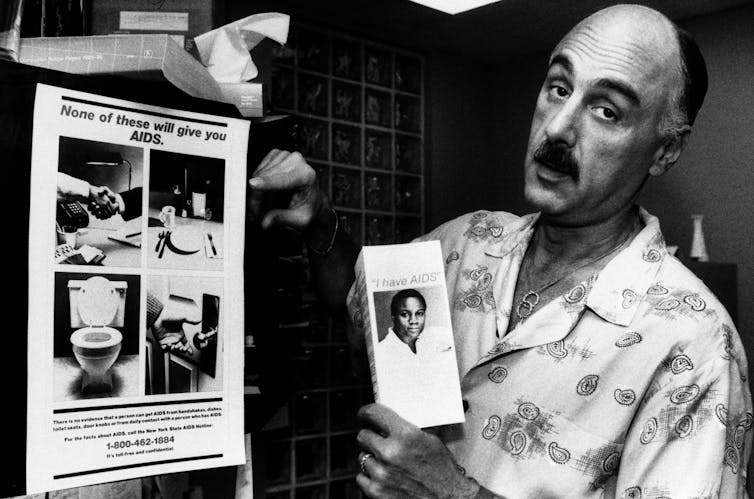

When Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the world’s first AIDS service organization, was founded in 1982, it was regular people trying to meet the needs of all people living with AIDS. Its workforce of volunteers provided HIV prevention education as well as physical, emotional and legal support.

At the start of the epidemic, AIDS was considered a “gay plague,” and to be openly queer was to risk abandonment, eviction, assault or worse. Families disowned their children. Hospitals turned patients away. Funeral homes refused bodies. And many people with AIDS found themselves alone and in need.

Public officials didn’t just fail to act – they refused to acknowledge that anything was happening at all. Elected leaders such as President Ronald Reagan and Sen. Jesse Helms stoked the moral panic guiding public policy by declaring people with AIDS “perverted human being(s).”

In 2025, with the Trump administration cutting federal funding for HIV research and support services and restricting protections and services for LGBTQ+ people, studying how everyday people approached the early AIDS crisis provides a model for surviving through innovation, commitment and community.

Stories informing the present

“I think 26,000 people died before (Reagan) even bothered to utter the word ‘AIDS,’” said Tim Sweeney, former executive director of Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

This quote is featured in the GMHC Stories Oral History Project, a collection of over 100 interviews with former volunteers, staff and donors from the first 15 years of the organization. Along with our colleague Julia Haager, we and our team at Binghamton University’s Human Sexualities Lab compiled these interviews. Acquired by the Manuscripts and Archives Division of The New York Public Library, the collection is scheduled to open in fall 2025, showcasing how everyday people responded to the AIDS crisis.

These stories document how a community presented with a set of circumstances threatening their very existence built a self-sustaining organization to advocate for and provide care to each other outside institutional support. They did this while enduring grief, standing up to external threats and navigating internal tensions.

Improvisation for survival

The work was an ongoing challenge. Organizations dedicated to aiding people affected by AIDS such as Gay Men’s Health Crisis were left to fund their own survival – and defend their right to do the work. When North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms moved in 1988 to eliminate federal support for AIDS service programs that mentioned homosexuality, it severely limited AIDS prevention efforts nation wide. However, GMHC had the foresight to fund its more explicit education materials with private donations.

At the beginning of the epidemic, queer New Yorkers and their allies had to improvise new systems of care in the absence of state and federal support. “People often (ask) me, what was the model you worked off of?” said Sweeney. “And I said, there was no model, there was just a muddle. We just made it up the whole time.”

What they created almost overnight was staggering. “There were over 1,000 volunteers in the agency,” recalled staff member Tom Weber, who started at GMHC as an office volunteer in 1988. “We would have orientations every single week, and they would flood in.”

One of the most well-known expressions of that volunteer labor was the buddy program, where lay caregivers provided emotional and practical support to people living with AIDS. “A lot of people were not alone in their death because of the work that we did,” said Barbara Danish, who led the buddy program from 1996 to 2002.

Education and prevention were also grounded in queer culture and community. Unlike early depictions of AIDS in the media that reduced patients to “vectors” of transmission, it was defiantly sex-positive. “We came up with shit that no one in the world had ever done,” Sweeney said. “Because finally it was gay men saying … we’re going to talk to each other about how to stay safe, healthy and sexy.”

When that sense of mission extended to emotional survival, humor and unapologetically queer culture were critical to bearing the weight of the work. “Sometimes you just break down and cry for an hour. But that’s how you survive it – by staying authentic to your emotions,” said Tommy Thomson, former director of client programs. She recalled how staff member “Carolotta,” or Carl, would sometimes put condoms and chocolate in a basket and go from office to office, frequently in drag. He would offer either or both to make people feel better. “He’d make you remember that you weren’t alone, and that we all know how hard it is. That’s part of what held you together.”

Internal tensions

Although Gay Men’s Health Crisis remained mission-driven, its internal politics were never simple. As it grew in size and national stature, it confronted the limits of its founding identity.

Founded by, and initially serving, primarily white gay men, GMHC sometimes struggled to adapt to the emerging realities of the epidemic. While AIDS also affected people of color, women and intravenous drug users from the outset, much of the agency’s early prevention and outreach work was designed with gay men in mind.

By the late 1980s, the increase in AIDS cases among white gay men had begun to plateau, while rates among Black and Latino people, women and IV drug users continued to rise sharply into the next decade. Women and people of color who were deeply embedded in GMHC’s operations nonetheless had to navigate assumptions about whose needs were prioritized – assumptions that often manifested in how resources were allocated and services were designed. As GMHC expanded its outreach to Black and Latino populations, it struggled to be culturally responsive and build trust in communities that had long been underserved and stigmatized.

As GMHC grew, it became more and more successful in fundraising and visibility, while smaller organizations sometimes struggled to access resources. This led to growing tensions, particularly in communities of color, where local groups feared that GMHC’s expansion would limit funding and undercut their efforts at community-specific approaches to care and prevention. In addition, efforts to address racism, sexism and cultural insensitivity encountered both support and indifference.

Yet, staff and volunteers continued to push – reshaping messaging, fighting for inclusive programming, and holding conversations about race, gender, power and public health. For staff and volunteers, the agency was a complicated institution that could both empower and marginalize. Its strength, and its struggle, was learning how to expand without losing sight of the legacy and history it was built on.

A guide for today

Forty years later, LGBTQ+ people face a new set of crises in a landscape riddled with dangers.

Trans health care is being banned in multiple states. Book bans and surveillance laws are targeting queer youth. Anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric is fueling violence and censorship. Funding for HIV prevention and research is disappearing even as new infections persist. Black and brown communities still face disproportionate barriers to health care and housing. Decades of scientific progress and medical discoveries are coming to a halt with funding cuts under the Trump administration.

And yet many of the same questions and challenges remain: Who gets left behind when public health systems collapse under political pressure or moral panic? Who will do the work when institutions fail? What does it mean to care for one another in the midst of the wreckage? How do people come together across differences?

The history of GMHC is more than memory – it is a lesson in the possibility of care, creativity and community, especially in the face of fear and uncertainty today. It shows how people can come together – not just to demand policy change, but to directly meet one another’s needs with whatever resources they have. It is a reminder that mutual aid is powerful; that grief can coexist with joy; and that queer resilience has always included laughter, desire and shared vulnerability. In a time of renewed political backlash and public health failures, GMHC’s story is more than history – it’s a guide. Today, the staff and volunteers at GMHC continue their work to confront the epidemic and uplift the lives of all people affected by AIDS.

“We’d say to them, ‘You’re just ordinary citizens doing extraordinary things,’” Sweeney said. “And we really meant that.”

Sean G. Massey was a volunteer and staff member at Gay Men's Health Crisis (GMHC), the organization that is being discussed in this article, from 1988-1998.

Casey W. Adrian and Eden Lowinger do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

US exit from the World Health Organization marks a new era in global health policy – here’s what the

The US will no longer participate in the WHO’s global influenza monitoring system – a shift experts…

3 things to know about Kevin Warsh, Trump’s nod for Fed chair

Trump’s pick to helm the Fed is well known in the financial world, but his monetary policy views have…

I’m a former FBI agent who studies policing, and here’s how federal agents in Minneapolis are underm

A policing scholar and former FBI special agent lays out the established principles of policing and…