When developing countries band together, lifesaving drugs become cheaper and easier to buy − with tr

Pharmaceutical companies have little incentive to sell drugs to countries that can’t afford them. But bargaining together can increase access to vital treatments worldwide.

Procuring lifesaving drugs is a daunting challenge in many low- and middle-income countries. Essential treatments are often neither available nor affordable in these nations, even decades after the drugs entered the market.

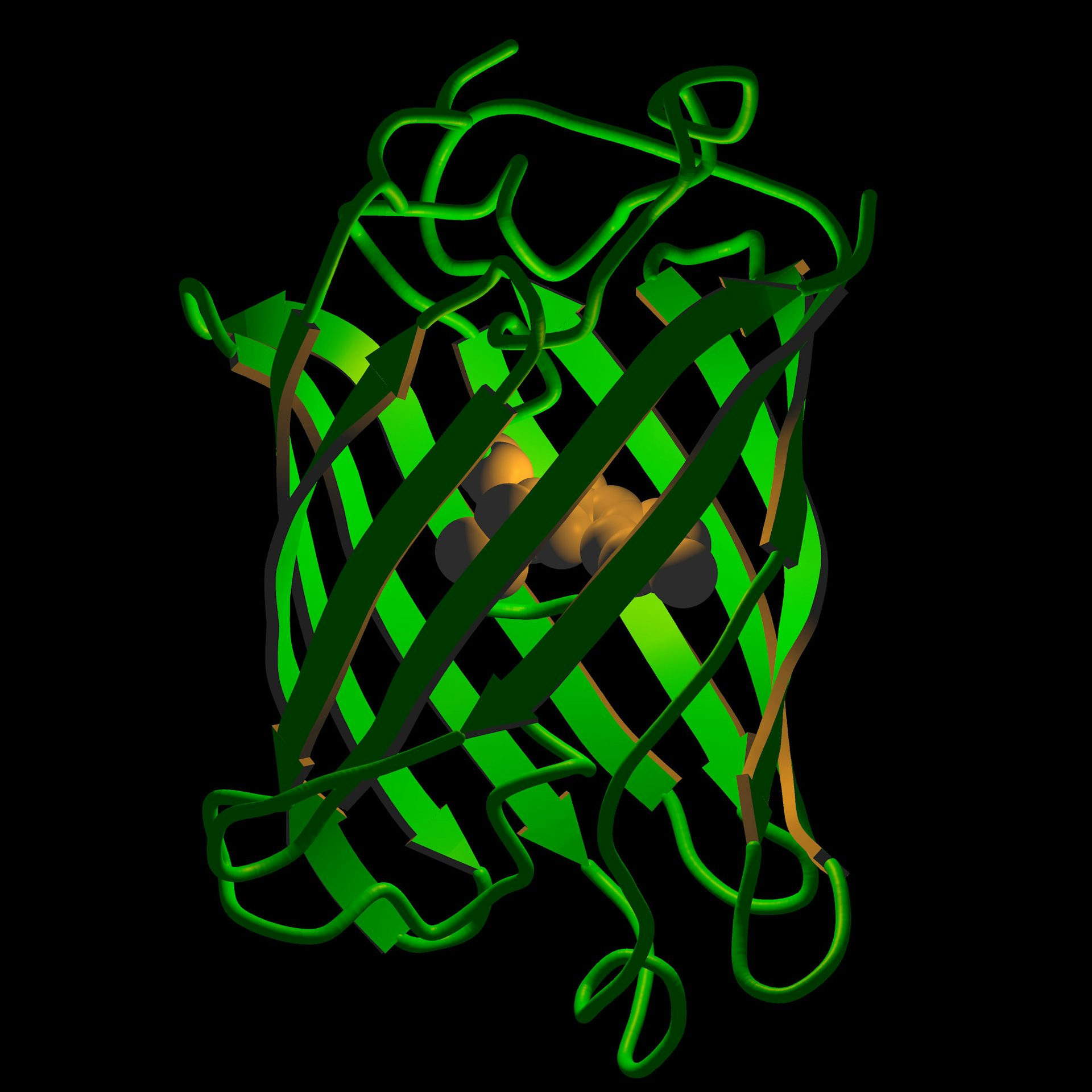

Prospective buyers from these countries face a patent thicket, where a single drug may be covered by hundreds of patents. This makes it costly and legally difficult to secure licensing rights for manufacturing.

These buyers also face a complex and often fragile supply chain. Many major pharmaceutical firms have little incentive to sell their products in unprofitable markets. Quality assurance adds another layer of complexity, with substandard and counterfeit drugs widespread in many of these countries.

Organizations such as the United Nations-backed Medicines Patent Pool have effectively increased the supply of generic versions of patented drugs. But the problems go beyond patents or manufacturing – how medicines are bought are also crucially important. Buyers for low- and middle-income countries are often health ministries and community organizations on tight budgets that have to negotiate with sellers that may have substantial market power and far more experience.

We are economists who study how to increase access to drugs across the globe. Our research found that while pooling orders for essential medicines can help drive down costs and ensure a steady supply to low- and middle-income countries, there are trade-offs that require flexibility and early planning to address.

Understanding these trade-offs can help countries better prepare for future health emergencies and treat chronic conditions.

Pooled procurement reduces drug costs

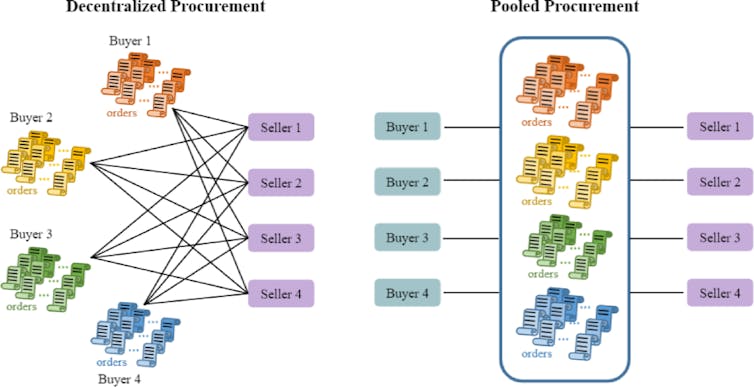

One strategy low-income countries are increasingly adopting to improve treatment access is “pooled procurement.” That’s when multiple buyers coordinate purchases to strengthen their collective bargaining power and reduce prices for essential medicines. For example, pooling can help buyers meet the minimum batch size requirements some suppliers impose that countries purchasing individually may not satisfy.

Countries typically rely on four models for pooled drug procurement:

One method, called decentralized procurement, involves buyers purchasing directly from manufacturers.

Another method, called international pooled procurement, involves going through international institutions such as the Global Fund’s Pooled Procurement Mechanism or the United Nations.

Countries may also purchase prescription drugs through their own central medical stores, which are government-run or semi-autonomous agencies that procure, store and distribute medicines on behalf of national health systems. This method is called centralized domestic procurement.

Finally, countries can also go through independent nonprofits, foundations, nongovernmental organizations and private wholesalers.

We wanted to understand how different procurement methods affect the cost of and time it takes to deliver drugs for HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis, because those three infectious diseases account for a large share of deaths and cases worldwide. So we analyzed over 39,000 drug procurement transactions across 106 countries between 2007 and 2017 that were funded by the Global Fund, the largest multilateral funder of HIV/AIDS programs worldwide.

We found that pooled procurement through international institutions reduced prices by 13% to 20% compared with directly buying from drug manufacturers. Smaller buyers and those purchasing drugs produced by only a small number of manufacturers saw the greatest savings. In comparison, purchasing through domestic pooling offered less consistent savings, with larger buyers seeing greater price advantages.

The Global Fund and the United Nations were especially effective at lowering the prices of older, off-patent drugs.

Trade-offs with pooled procurements

Cost savings from pooled drug procurement may come with trade-offs.

While the Global Fund reduced unexpected delivery delays by 28%, it required buyers to place orders much earlier. This results in longer anticipated procurement lead time between ordering and delivery – an average of 114 days more than that of direct purchases. In contrast, domestic pooled procurement shortened lead times by over a month.

Our results suggest a core tension: Pooled procurement improves prices and reliability but can reduce flexibility. Organizations that facilitate pooled procurement tend to prioritize medicines that can be bought at high volume, limiting the availability of other types of drugs. Additionally, the longer lead times may not be suitable for emergency situations.

With the spread of COVID-19, several large armed conflicts and tariff wars, governments have become increasingly aware of the fragility of the global supply chain. Some countries, such as Kenya, have sought to reduce their dependence on international pooling since 2005 by investing in domestic procurement.

But a shift toward domestic self-sufficiency is a slow and difficult process due to challenges with quality assurance and large-scale manufacturing. It may also weaken international pooled systems, which rely on broad participation to negotiate better terms with suppliers.

Interestingly, we found little evidence that international pooled procurement influences pricing for the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, a major purchaser of HIV treatments for developing countries. PEPFAR-eligible products do not appear to benefit more from international pooled procurement than noneligible ones.

However, domestic procurement institutions were able to secure lower prices for PEPFAR-eligible products. This suggests that the presence of a large donor such as PEPFAR can cut costs, particularly when countries manage procurement internally.

USAID cuts and global drug access

While international organizations such as the Medicines Patent Pool and the Global Fund can address upstream barriers such as patents and procurement in the global drug supply chain, other institutions are essential for ensuring that medicines actually reach patients.

The U.S. Agency for International Development had played a significant role in delivering HIV treatment abroad through PEPFAR. The Trump administration’s decision in February 2025 to cut over 90% of USAID’s foreign aid contracts amounted to a US$60 billion reduction in overall U.S. assistance globally. An estimated hundreds of thousands of deaths are already happening, and millions more will likely die.

The World Health Organization warned that eight countries, including Haiti, Kenya, Nigeria and Ukraine, could soon run out of HIV treatments due to these aid cuts. In South Africa, HIV services have already been scaled back, with reports of mass layoffs of health workers and HIV clinic closures. These downstream cracks can undercut the gains from efforts to make procuring drugs more accessible if the drugs can’t reach patients.

Because HIV, tuberculosis and malaria often share the same treatment infrastructure – including drug procurement and distribution networks, laboratory systems, data collection, health workers and community-based services – disruption in the management of one disease can ripple across the others. Researchers have warned of a broader unraveling of progress across these infectious diseases, describing the fallout as a potential “bloodbath” in the global HIV response.

Research shows that supporting access to treatments around the world doesn’t just save lives abroad. It also helps prevent the next global health crisis from reaching America’s doorstep.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

50 years ago, the Supreme Court broke campaign finance regulation

A gobsmacking amount of money is spent on federal elections in the US. The credit or blame for that…