Colorado’s fentanyl criminalization bill won’t solve the opioid epidemic, say the people most affect

Incarcerating people who use drugs is associated with increased overdose deaths after release and high rate of recidivism.

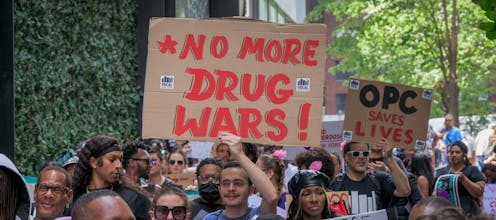

Colorado passed the Fentanyl Accountability and Prevention Bill in May 2022. The legislation made the possession of small amounts of fentanyl a felony, rather than a misdemeanor.

Felonies are more likely than misdemeanors to result in a prison sentence.

Time in prison is associated with an increased risk of fatal overdose in the year after release. People with felonies on their record often struggle to find a job or rent an apartment.

In 2023, lawmakers in 46 states passed legislation similar to Colorado’s. They introduced more than 600 bills related to fentanyl criminalization and enacted over 100 other laws to attempt to curb the opioid epidemic.

Possession of small amounts of ketamine, GHB and other criminalized drugs is also a felony in Colorado.

I’m an assistant professor of medicine, social epidemiologist and community researcher who studies mass incarceration as a public health threat. I am a member of the Right Response Coalition, which advocates for community rather than criminal-legal responses to behavioral health needs in Colorado. Recently, my work has focused on how increasing criminal penalties for fentanyl possession in Colorado affects the individuals and communities most impacted by such laws.

Our team conducted 31 interviews with Colorado policymakers, peer support specialists, law enforcement, community behavioral health providers and people providing behavioral health in prisons and jails to explore a variety of perspectives on Colorado’s Fentanyl Accountability and Prevention Bill and the role of the criminal-legal system in addressing substance use and overdose.

Most of our interviewees agreed that criminalization alone wouldn’t solve the opioid epidemic.

“You can’t incarcerate yourself to sobriety,” said a rural law enforcement officer. “You can’t incarcerate yourself out of the drug problem in America.”

Criminalization of drug use

Incarceration and substance use are deeply intertwined. The U.S. houses one-quarter of the world’s incarcerated population – largely due to policies created during the “war on Drugs” of the 1980s. The war on drugs included mandatory minimum sentencing for drug-related charges and “three strikes” laws that lengthened sentences after multiple charges.

Today, one-fifth of the U.S. incarcerated population has a drug-related charge.

Incarceration is often seen as a deterrent, but research shows it is not actually associated with reduced drug use. Instead, people recently released from incarceration are more likely to die of a fatal overdose and face a high likelihood of reincarceration.

Perspectives of front-line workers

All 31 of the participants in our study supported policies to prevent fentanyl overdoses. However, most thought that use of police and incarceration as avenues to do so was misguided.

We spoke to some individuals who felt the bill was appropriate, but most felt that increased criminalization perpetuates stigma against people who use drugs. They also saw the law as ignoring the root causes of the opioid epidemic, which include a lack of voluntary community-based treatment options. They also said the law creates stressful law enforcement encounters that can perpetuate drug use as a coping mechanism.

“It just seems like there’s no getting away from [the police], they’re everywhere,” said an urban peer support specialist. “I got arrested by the same cops, I don’t know how many times. And then it makes you want to try to be avoidant or run because they’re not going to help you.”

Participants worried that the policy has an inadvertent chilling effect, deterring individuals from calling 911 when an overdose occurs.

“Most people with substance abuse are not trying to report anything or get help for fear of going to jail,” one rural provider said. “It’s so stigmatized that everyone’s just scared to do that.”

Participants largely thought that counties were using incarceration as a default treatment setting and that it wasn’t an ideal solution.

“[I] don’t want to see [people] incarcerated, but I don’t want ‘em to die either,” said an urban peer support specialist.

The people we interviewed pointed to a lack of community-based care options that could come before people are incarcerated. Those options include substance use treatment centers, mental health services and community health centers.

Substance use treatment

Colorado’s fentanyl bill did more than just increase penalties. It also provided additional funding for a state naloxone program and required that all jails provide medications for opioid use disorder.

These medications include methadone, buprenorphine and extended-release naltrexone. All are part of an established public health strategy shown to reduce overdose deaths and opioid use. They’re also shown to increase engagement with non-jail-based treatment and reduce reincarceration.

However, jail capacity and the lack of treatment options based in one’s community play a large role in which medications are offered and to whom. For example, only 11 out of Colorado’s 46 counties with a county jail have an opioid treatment program in the community that can dispense methadone. Therefore, some facilities do not offer all medications, or only offer medications to individuals with an active prescription or to certain populations such as pregnant people.

Investing in community solutions

Based on our study’s findings, my study co-authors and I believe increased criminal penalties should not be the solution for linking individuals to treatment. Instead, there should be more investment in long-term community solutions.

One such solution is Denver’s Substance Use Navigation Program. The program sends behavioral health specialists to emergency calls to prevent legal involvement when someone is experiencing distress related to mental health, poverty, homelessness or substance use. In many cases, those individuals are then routed to services rather than jails.

Our findings also lead us to believe there is a need for more participatory policymaking processes when it comes to fentanyl legislation, and that policymakers should more closely work with the people who will be most impacted by new legislation. Most of our participants agree.

“[I] don’t think that [the] state realized how difficult it is,” said a rural provider about giving medication-assisted treatment in jail, an increasing need as more people are arrested for fentanyl possession. “They probably should come here and visit us.”

Katherine LeMasters received funding from the Colorado Department of Human Services, Behavioral Health Administration. Katherine LeMasters is part of the Right Response Coalition.

Read These Next

US exit from the World Health Organization marks a new era in global health policy – here’s what the

The US will no longer participate in the WHO’s global influenza monitoring system – a shift experts…

From Colonial rebels to Minneapolis protesters, technology has long powered American social movement

Smartphone video, ICE-tracking apps and 3D-printed whistles have been emblematic of the protests in…

Rescheduling marijuana would be a big tax break for legal cannabis businesses – and a quiet form of

Consequences will go far beyond the tax bill that businesses face, a tax law professor explains.