1 in 8 U.S. deaths from 2020 to 2021 came from COVID-19 – leaving millions of relatives reeling from

COVID-19 deaths tend to be more unexpected and traumatic than other types of deaths. A sociologist explains the mental health burdens facing the millions who’ve lost a relative to the coronavirus.

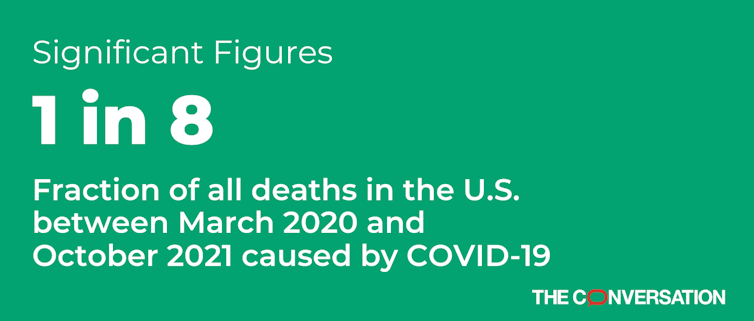

COVID-19 was the third-most-common cause of death between March 2020 and October 2021 in the U.S., behind only heart disease and cancer, according to a recent study.

Older adults face the greatest risk of dying from COVID-19, but infection with the coronavirus remains a serious risk for younger people, too. In 2021, COVID-19 was the leading cause of death in adults aged 45 to 54, the second leading cause for adults aged 35 to 44 and the fourth leading cause for those aged 15 to 34.

As sociologists who study population health, we have been assessing how losing a loved one to COVID-19 has affected people’s well-being. Our research shows that more than 9 million people have lost a close relative to COVID-19 in the U.S. This dramatic rise in bereavement is troubling because our research finds that COVID-19 bereavement not only increases people’s risk of depression, but can make them uniquely vulnerable to mental distress.

The distinctness of grieving COVID-19 deaths

Researchers have a sense of what constitutes “good” and “bad” deaths. Bad deaths are those that involve pain or discomfort and happen in isolation. Their unexpectedness also makes these deaths more distressing. People whose loved ones die “bad deaths” tend to report greater mental distress than those whose loved ones died in more favorable circumstances.

COVID-19 deaths often bear many hallmarks of “bad” deaths. They are preceded by physical pain and distress, often occur in isolated hospital settings and happen suddenly – leaving family members unprepared. The ongoing nature of the pandemic has inflicted an added layer of agony, as individuals are grieving during a time of protracted social isolation, economic precarity and general uncertainty.

In another recent study, our team used national survey data from 27 countries to test whether the mental health impacts of COVID-19 deaths are more severe than death from other causes. We focused on the case of spousal death and compared two groups of people: those whose spouses died of COVID-19 in the pandemic’s first wave and those whose spouses died of other causes just before the pandemic began. We found that COVID-19 widows and widowers face higher rates of depression and loneliness than expected based on widow and widower mental health outcomes pre-pandemic.

The secondary population health consequences of COVID-19 deaths

The outsized effects of COVID-19 deaths on grieving spouses’ mental health is troubling because we estimate that nearly 500,000 people have already lost a spouse to COVID-19 in the U.S. alone. The mental health problems that people face after losing a loved one can also lead to declines in physical health and even increase a person’s risk of death.

Our research suggests that COVID-19 not only increased rates of family bereavement, but that people who lost loved ones to the coronavirus were particularly distressed afterward. But we studied only widowhood; future research needs to identify the potentially unique health, social and economic consequences of COVID-19 losses for other bereaved relatives.

With COVID-19 representing 1 in every 8 deaths between March 2020 and October 2021, there are millions of people who could benefit greatly from financial, social and mental health support. It is also critical to continue taking steps to prevent future COVID-19 deaths. Each death averted not only saves a life but also saves numerous loved ones from the harm that follows these tragedies.

Emily Smith-Greenaway receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Ashton Verdery receives funding from The National Institute on Aging (1R01AG060949).

Shawn Bauldry receives funding from the National Institute on Aging.

Haowei Wang does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Why ICE’s body camera policies make the videos unlikely to improve accountability and transparency

For body cameras to function as transparency tools, wrongdoing would have to be consistently penalized,…

Artists and writers are often hesitant to disclose they’ve collaborated with AI – and those fears ma

Whether they’re famous composers or first-year art students, creators experience reputational costs…

When civil rights protesters are killed, some deaths – generally those of white people – resonate mo

From the civil rights era of the 1960s until today, white victims of government violence have received…