In Mike Pence, US evangelicals had their '24-karat-gold' man in the White House. Loyalty may tarnish

As Mike Pence prepares for life after the vice presidency, a scholar of religion looks back at the political and religious conversions that informed the politician's worldview.

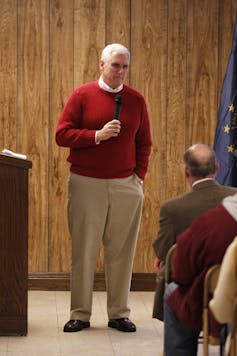

Mike Pence has remained one of the only constants in the often chaotic Trump administration.

Variously described as “vanilla,” “steady” and loyal to the point of being “sycophantic,” he is, in the words of one profile, an “everyman’s man with Midwest humility and approachability,” and in another, a “61-year-old, soft-spoken, deeply religious man.”

But that humility and loyalty are being tested as his tenure as vice president draws to an end. “I hope Mike Pence comes through for us,” Trump told supporters at a rally on Monday, seemingly under the mistaken belief that Pence can overturn the election result as he presides over the Electoral College vote count at a joint session of Congress today.

Balancing the ticket

Throughout the past four years, the vice president has offered a striking contrast to the mercurial, abrasive temperament of his commander in chief. Indeed, in his acceptance speech at the 2016 Republican National Convention, Pence joked that he’d been chosen because Trump, with his “large personality,” “colorful style,” and “lots of charisma,” was “looking for some balance on the ticket.”

Commentators have attributed Pence’s steadiness to his Hoosier roots and his “savvy political operator” skills. But it is his religious beliefs that perhaps inform his politics and style more than anything else; as Pence has oft repeated, he is “a Christian, conservative and Republican – in that order.”

In a 2011 profile during Pence’s run for Indiana governor, noted state political columnist Brian Howey remarked, “Pence doesn’t just wear his faith on his sleeve, he wears the whole Jesus jersey.”

It isn’t a characterization that Pence has shied away from. “My Christian faith is at the very heart of who I am,” Pence said during the 2016 vice presidential debate.

Richard Land, former president of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission and current president of Southern Evangelical Seminary in Charlotte, told the Atlantic in 2018, “Mike Pence is the 24-karat-gold model of what we want in an evangelical politician. I don’t know anyone who’s more consistent in bringing his evangelical Christian worldview to public policy.”

But as a scholar of U.S. religion and culture, I believe that Pence’s faith and political identities are more complex than these statements suggest. In fact, one can trace three distinct conversion experiences in his biography.

Three-point conversion

Growing up in an Irish Catholic family with five siblings, working-class roots and Democratic political commitments, Pence attended Catholic school, served as an altar boy at his family’s church, idolized John F. Kennedy and was a youth coordinator for the local Democratic Party in his teens.

It was as a freshman at Hanover College in 1978 that Pence experienced an evangelical conversion while attending a music festival in Kentucky billed as the “Christian Woodstock.”

For some years afterward he remained active in the Catholic Church, attending Mass regularly, serving as a youth minister and seriously considering joining the priesthood. At the same time, he and his future wife Karen were part of a demographic shift of Americans who “had grown up Catholic and still loved many things about the Catholic Church, but also really loved the concept of having a very personal relationship with Christ,” as a close friend put it.

By the mid-1990s he was a married father of three who identified as a “born-again, evangelical Catholic,” an unusual term that has caused some consternation among both evangelicals and Catholics.

In subsequent interviews, Pence has spoken freely about how his 1978 conversion gave him a “personal relationship with Jesus Christ” that “changed everything.” But he has tended to avoid labeling his religious views when pressed, referring to himself as a “pretty ordinary Christian” who “cherishes his Catholic upbringing.” He has attended nondenominational evangelical churches with his family since at least 1995.

Pence’s political conversion was more clear cut. Though he voted for Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election, he quickly came to embrace Ronald Reagan’s economic and social conservatism and his populist appeal. In a 2016 speech at the Reagan Library, Pence credited Reagan with inspiring him to “leave the party of my youth and become a Republican like he did.” “His broad-shouldered leadership changed my life,” he said. Pence has frequently compared Trump to Reagan, arguing that they have the same “broad shoulders.”

Pence ran unsuccessfully for Congress in 1988 and 1990, and the second bruising loss precipitated a third conversion, this time in political style. In a 1991 published essay titled “Confessions of a Negative Campaigner,” he described himself as a sinner and wrote of his “conversion” to the belief that “negative campaigning is wrong.”

Between 1992 and 1999, Pence honed his blend of family values and fiscal conservatism in an eponymous conservative talk show.

The show’s popularity provided a springboard to a successful run for Congress in 2000. During his six terms in the House, Pence acquired a reputation for “unalloyed traditional conservatism” and principled opposition to Republican Party leadership on issues like No Child Left Behind and Medicare prescription drug expansion.

Religious acts

In addition to his “unsullied” reputation as a “culture warrior,” he also attracted attention for following the “Billy Graham Rule” of avoiding meeting with women alone and avoiding events where alcohol was served when his wife was not present.

During the 2016 vice presidential debate, Pence said that his entire career in public service stems from a commitment to “live out” his religious beliefs, “however imperfectly.”

One of those beliefs is his opposition to abortion, grounded in his reading of particular biblical passages. As a congressman in 2007, he was the first to sponsor legislation defunding Planned Parenthood, and did so repeatedly until the first defunding bill passed in 2011. “I long for the day when Roe v. Wade is sent to the ash heap of history,” he said at the time.

In 2016, over the objections of many Republican state representatives, he signed the most restrictive set of anti-abortion measures in the country into law, making him a conservative hero. Among other things, the bill prevented women from terminating pregnancies for reasons including fetal disability such as Down syndrome. Although opponents succeeded in getting the bill overturned in the courts, Indiana is still seen as one of the most anti-abortion states in America.

As vice president, Pence also cast the tie-breaking Senate vote to allow states to withhold federal family planning funds from Planned Parenthood in 2017.

Pence has also been an outspoken opponent of LGBTQ rights. He opposed the inclusion of sexual orientation in hate crimes legislation and the end of the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy. He likewise supported both state and federal constitutional amendments to ban same-sex marriage, and expressed disappointment at the 2015 Obergefell decision, which required all states to recognize such unions.

At the same time he has been a strong supporter of “religious freedom,” particularly for Christians.

In March 2015, as Indiana governor, he signed the state’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act “to ensure that religious liberty is fully protected.” The act ignited a firestorm of nationwide controversy: Critics alleged that it would allow for individuals and businesses to legally discriminate against members of the LGBTQ community. Under pressure from LGBTQ activists, liberals, business owners and moderate Republicans, Pence signed an amendment a week later stipulating that it did not authorize discrimination.

Staked reputation

Pence’s religious and political biography mirrors key political and religious shifts over the past 40 years, from the rise of the religious right and its growing influence in the Republican Party to the conservative coalition of evangelicals and Catholics across denominational lines, to the legacy of the “outsider” celebrity president.

These threads converge in Mike Pence, whose “24-karat,” “unalloyed” conservative credentials were instrumental in rallying evangelical voters behind Trump in the 2016 election and who has staked his political future on continuing to defend him.

Deborah Whitehead does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

I was teaching virtue and knowledge while lying on the side

While rationalizing deception is easy to do, developing the virtue of truthfulness is not.

In its hunt for critical minerals, the US is misconstruing what is and is not America’s

There’s a growing interest in mining the ocean seabed for minerals essential to technology. But whose…