When a child chooses a donor to sponsor them, it's a new twist on a surprisingly old model of intern

No matter who chooses whom, many sponsors of children in need see God as the real driving force when they enter this arrangement with far-away strangers.

World Vision, the world’s largest Christian humanitarian organization, revised its 70-year-old child sponsorship model in 2019. Initially piloted in seven churches across the United States, it claims to “flip the script” with its new Chosen program.

Donors still pay a set amount each month to aid a child in a low-income country, with whom they can write letters and exchange photos. But in the new program children select their donors instead of donors choosing them. World Vision is now extending the system to 22 countries, potentially affecting 180,000 children globally. Today, about 10 million children worldwide have sponsors, with 3.8 million tied to World Vision alone.

Chosen is World Vision’s latest response to an issue that has been on its radar since the 1970s. Critics, including scholars, journalists and even World Vision staff members, have argued that sponsorship augments donors’ sense of power while stripping poor children of theirs. Among other things, these critics have held that sponsorship lets people in wealthy nations “purchase” a foreign child to help.

Given these troubling power relations, and the association with buying a child, why do so many sponsorship nonprofits retain any kind of “choosing” at all?

Based on my recent book, “Christian Globalism at Home: Child Sponsorship in the United States,” my view is that choice is so embedded because of sponsorship’s little-known origins in Protestant Christianity and early capitalism. This history also clarifies why contemporary sponsors reject the parallels with a consumer purchase. For many sponsors, the difference lies in how they view God as the real driving force when they choose a child to support.

The roots of sponsorship

Historians have long assumed that secular humanitarians invented sponsorship just after World War I. Actually, the U.S. sponsorship model dates back to 1816, when the country’s first foreign missionaries started Protestant schools in Mumbai. The roots of this system extend even farther to a late 17th-century revolution in charitable fundraising.

European Protestants wanted alternatives to a medieval system in which charitable institutions depended largely on wealthy donors making deathbed bequests.

Turning to early capitalism, they saw how small-scale shareholders pooled their money and later split the profits. They created a similar approach to charity, which they called a “subscription”: Donors gave a small amount on a regular schedule to invest in God’s work and gain a “share” of heavenly rewards. The earliest sponsorship plans built on this idea and asked donors for a set amount a month to support a child during their years at a missionary school.

Most 19th-century sponsors belonged to the growing ranks of the middle class. When they invested in modern corporations, they expected accountability. Sponsorship also appealed to them on this basis because it offered a sense of control. Sponsors gave money to support one individual and could then observe the results in that child’s life.

It was a small leap for these 19th-century sponsors to begin requesting this or that child.

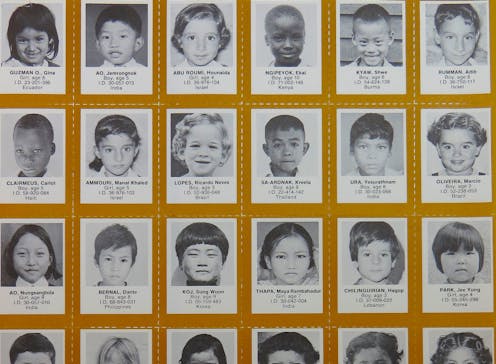

Following World War II, new sponsorship nonprofits, including World Vision, made choice into an essential part of their programs. They published rows of childen’s photos and descriptions in magazine advertisements and direct mailings. Sponsors could then call or mail in their selections. In the 1950s, World Vision told sponsors to linger “prayerfully” over the photos to hear which child God was telling them to choose. The approach proved instantly popular.

Why sponsors choose a child

Today, prospective sponsors look through profiles online or in person at sign-up tables. Each profile includes a child’s photo, some personal information, and details about their country. After six years of interviewing American sponsors and sitting at sign-up tables, I have a pretty good sense of why most people choose a particular child.

I worked primarily with Christians, who still make up the bulk of sponsors, including at World Vision, with its evangelical orientation. Not all Christians emphasize choice to the same degree. I found that evangelicals did so more than Catholic, mainline Protestant, or nonreligious sponsors. However, among people who do opt to select a child, my interviews showed similar patterns across all these groups. In order of importance, sponsors choose a child based on a shared birthday, their facial expression, country of origin, gender, highest need and name.

But, ultimately, most sponsors found it hard to explain: They told me it was a coincidence – such as having the same birthday – or a subtle pull that led them to a specific child. Some sponsors call it fate. Many Christians credit God.

Nichole attends Woodbury Lutheran Church in Minnesota, one of World Vision’s seven Chosen pilot sites. The 28-year-old engineer became a sponsor five years ago when she picked a child from a display in Woodbury’s lobby: “I was drawn to (the photo) for some reason,” she says. “I didn’t sit there and debate it. I think it was all God.”

Marilee Pierce Dunker, the daughter of World Vision’s founder Bob Pierce, calls these moments an “act of divine matchmaking.” She told me how sponsors often come to her sign-up table with a special request “for a child that is this age or born on this day…And we have a limited number of (profiles available) but there it is – the exact child.”

Nichole didn’t have specifics in mind, but later she did get a sense that “it was totally the Holy Spirit (arranging it) because I had friends meet that kid (later on) in Ethiopia and they told me, your personalities are so similar it’s crazy!”

God moments

Whether they call the driving force a God moment, fate or coincidence, sponsors say it’s what makes this choice unlike a mundane “purchase.” Yet the metaphor can still chafe.

Nichole is enthusiastic about the Chosen program for that reason. Junayet, a 6-year-old boy in Bangladesh, selected her photo from a display of potential Woodbury church sponsors. “When they flipped (the choice),” she explained, “that’s what I’d always wanted, because I’ve always been uncomfortable with choosing a kid.”

In that respect, World Vision is flipping the script. But in doing so, it reiterates what sponsorship has claimed for more than two centuries: God is the real catalyst when anyone chooses a faraway stranger.

Bringing God into this process is a legacy of sponsorship’s history at the intersection of Protestant missions and corporate shareholding. It brings Christianity and capitalism together, while also denying their close association. Based on my research, it’s a longstanding way that people in wealthy Christian-majority countries infuse morality into their economic system so that they can live – albeit often uneasily – with the resulting inequalities.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

In promotional videos for its Chosen program, World Vision makes it clear that God is still the guiding force – whether a sponsor or a child chooses. Sponsors say, “There are so many things that are bigger than us….Through God we’re intertwined.” Or they marvel at how “a child across the world” is serving as God’s “mouthpiece” by choosing them.

Nichole feels it too. After watching a video of Junayet choosing her, she told me, “I could see God in that moment.” Junayet “came up with all of the joy in the world. He literally ran to my photo. God’s hand is in all those moments.”

Hillary Kaell receives funding from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada and les Fonds de Recherche du Québec Société et Culture.

Read These Next

Counter-drone technologies are evolving – but there’s no surefire way to defend against drone attack

Companies are selling a range of anti-drone devices, from guns that fire nets to powerful laser weapons,…

Citizenship voting requirement in SAVE America Act has no basis in the Constitution – and ignores pr

The House has passed a bill to require proof of citizenship for voting. Although it likely won’t become…

Addiction affects your brain as well as your body – that’s why detoxing is just the first stage of r

Substance use disorders are widespread in the US, but many people wrongly equate detoxing with being…