An Italian teen is set to become the first millennial saint, but canonizing children is nothing new

Italian teenager Carlo Acutis, who died at the age of 15, is on the path to becoming a saint. A scholar explains the long history of child saints in the Catholic Church.

On Oct. 10, 2020, a young Italian named Carlo Acutis was beatified at a special Mass in the city of Assisi, putting the late teenager just one step away from sainthood. It allows Catholics to venerate him as “Blessed Carlo Acutis.”

Acutis died of leukemia in 2006, at the age of 15. Like other boys his age, he was avidly interested in computers, video games and the internet. He was also a devout Catholic who went to Mass daily and persuaded his mother as well to be a regular attendee. One of his pet projects was designing a webpage listing miracles across the globe associated with the bread and wine consecrated at Mass, believed by Catholics to be the body and blood of Christ.

After his death, townspeople began to attribute miracles to his intercession, including the birth of twins to his own mother four years after his death. His case was submitted to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, one of the offices that make up the papal administrative structure – the Curia – of the Catholic Church. It initiated the process of his official canonization in the Roman Catholic Church.

To non-Catholics, bestowing potential sainthood on one who died so young might seem puzzling. As a scholar of medieval liturgy and culture, I know that there has been a long history of including children among the saints approved for official recognition and veneration.

Who becomes a saint

For the first thousand years of Western Christian history, there was no formal process in Rome for declaring deceased persons as saints. In antiquity, Christians who became martyrs or imprisoned as confessors during persecutions were venerated after their deaths because of the strength of their beliefs. They were considered more perfect Christians because they chose to die rather than give up their faith.

Because of this, the martyrs were believed to be closely united with Christ in heaven. Individuals would pray at their tombs, asking the martyrs to intercede with Christ for help with spiritual or material problems, like healing from an illness.

Miracles were attributed to their intervention, since Christians believed that the tombs of the martyrs were holy places where they could access the healing power of God’s grace.

After Christianity spread throughout Europe, other Christians who led lives of unusual holiness were also venerated in the same way. These included bishops and priests, monks and nuns and other laypeople of exceptional virtue.

All of these saints were venerated locally, with the approval of the local bishop. However, the first saint to be officially canonized by a pope – Pope John XV – was St. Ulrich of Augsburg. Ulrich had served as the bishop of Augsburg for almost 50 years, building churches, revitalizing the clergy, and helping the residents resist a siege by invaders.

His canonization took place in A.D. 993 after the local bishop requested that the pope make the declaration.

From that time on popes would preside over the canonization process, and a set procedure for investigating potential candidates was established as part of the papal bureaucracy in Rome. After the Second Vatican Council, held from 1962 to 1965, called for a new vision of the church’s role in the world of the 20th century, the process was updated.

Today, proposed candidates are given the title “Servant of God.” If they were martyred or killed “in hatred of the faith,” they move to the next-to-last stage – beatification – and receive the title “Blessed.” Non-martyrs, if shown to have lived lives of “heroic virtue,” are given the title “Venerable Servant of God.”

Proceeding to beatification requires clear evidence of a miracle, often a healing, that is understood to have resulted from a direct prayer to the Servant of God asking for help. Claims of healing miracles are closely examined by a panel of medical experts. A second miracle is required for canonization.

Why child saints?

Over the centuries, several children have been proclaimed “Blessed” or “Saint.”

One group of child saints was venerated from late antiquity onward because of their mention in the gospels: the Holy Innocents. In the Gospel of Matthew, King Herod, threatened by rumors of the birth of a new king, sends soldiers to Bethlehem to kill all male infants and toddlers. These children became known as the Holy Innocents.

Because of their connection with the story of the birth of Jesus, sometime in the fifth century the commemoration of the Holy Innocents was set during Christmas week, Dec. 28 in the Western Church. This day is observed by all Catholics even today.

Sometimes child saints have been canonized as part of a larger group of martyrs. For example, among those martyred in China for their Christian faith are 120 Chinese Catholics killed between 1648 and 1930. Members were recognized for their unswerving dedication to the Catholic faith during several periods of intense persecution.

They were canonized by Pope St. John Paul II in 2000. In his homily on that day, the pope made special mention of the heroic deaths of two of them: 14-year-old Anna Wang and 18-year-old Chi Zhuzi, both of whom died in 1900.

Other child saints were canonized as individuals. One modern example is Maria Goretti, an Italian peasant girl murdered in 1902. Only 11 years old, she was alone at the home her impoverished family shared with another family when she was attacked by the young adult son of that family.

He attempted to rape her and stabbed her when she fought him off. Maria died the next day in a hospital after stating that she forgave her attacker and prayed that God might forgive him, too.

News of this spread quickly across Italy, and stories of miracles followed soon after. Maria was canonized in 1950 and quickly became a popular patron saint for young girls.

A few child saints were deemed to have demonstrated heroic virtue in other ways. In 1917, three peasant children from the town of Fatima in Portugal claimed to have received visions of the Blessed Virgin Mary. News of this spread widely, and the location became a popular pilgrimage site. The oldest child, Lucia, became a nun and lived into her 90s; her cause for sainthood is still in process.

However, her two cousins, Francisco and Jacinta Marto, died young of complications from the Spanish flu: Francisco in 1918 at the age of 10, and Jacinta in 1919, age 9. The two were beatified in 2000 by Pope St. John Paul II and canonized by Pope Francis in 2017.

They were the first child saints who were not martyrs. It was their “heroism” and “life of prayer” that was considered to be holy. There were other child saints too who were canonized for reasons other than being martyrs, yet led lives considered exemplary.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

But there were also those who were dropped from the official list of saints because of details that were later revealed. One such case was of a 2-year-old Christian boy Simon from Trent, Italy, whose body was found in the cellar of a Jewish family in 1475. Simon’s body was on display and miracles were attributed to him. It was 300 years later that the Jews of Trent were cleared of murder charges. In 1965 his name was removed from the Calendar of Saints by Pope Paul VI.

Nonetheless, this long history shows that sanctity is not limited to adults who lived in the distant past. In the eyes of the Catholic Church, an ordinary teenager in the 21st century too can be worthy of veneration.

Joanne M. Pierce does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Housing First helps people find permanent homes in Detroit − but HUD plans to divert funds to short-

Detroit’s homelessness response system could lose millions of dollars in federal funding for permanent…

When unpaid cooking, cleaning and child care get a dollar value, income inequality in the US shrinks

Women’s unpaid work at home has declined much more than men’s contributions have increased.

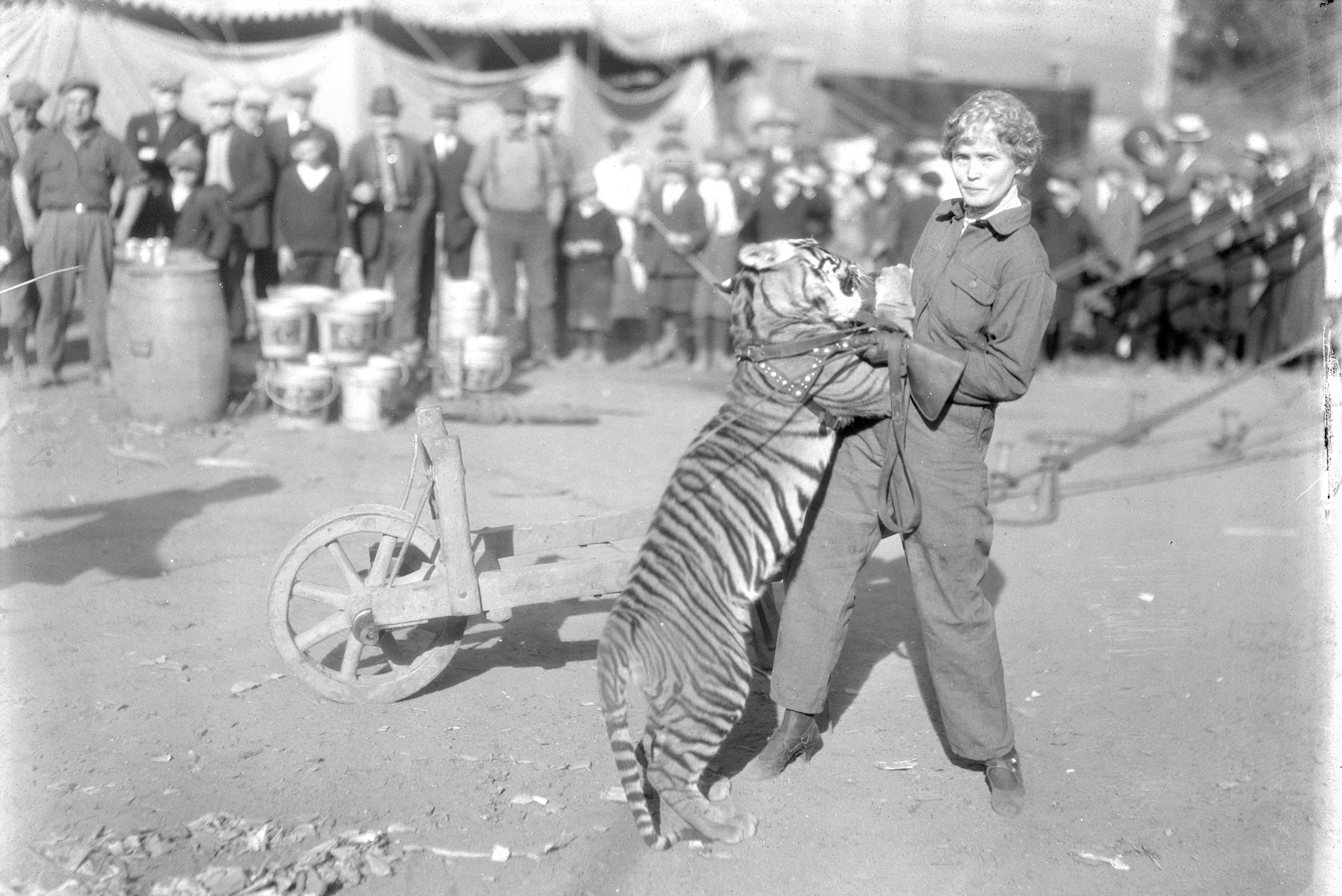

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.