How the needs of monks and empire builders helped mold the modern-day office

The coronavirus epidemic has made us all rethink our workspaces. But the needs of the times have always influenced the office space – whether for the colonial empire or a growing commerce.

The coronavirus pandemic has forced most people to create an office space of their own – whether by devoting a room in our homes for work, sitting socially distanced in common areas or just creating a “Zoom worthy” corner in a bedroom.

As a scholar who researches and designs learning and workspaces, I’m aware how the modern-day workplace was shaped over several centuries. But few people may know that the origins of the office can be found in the monasteries of medieval Europe.

Early origin in monasteries

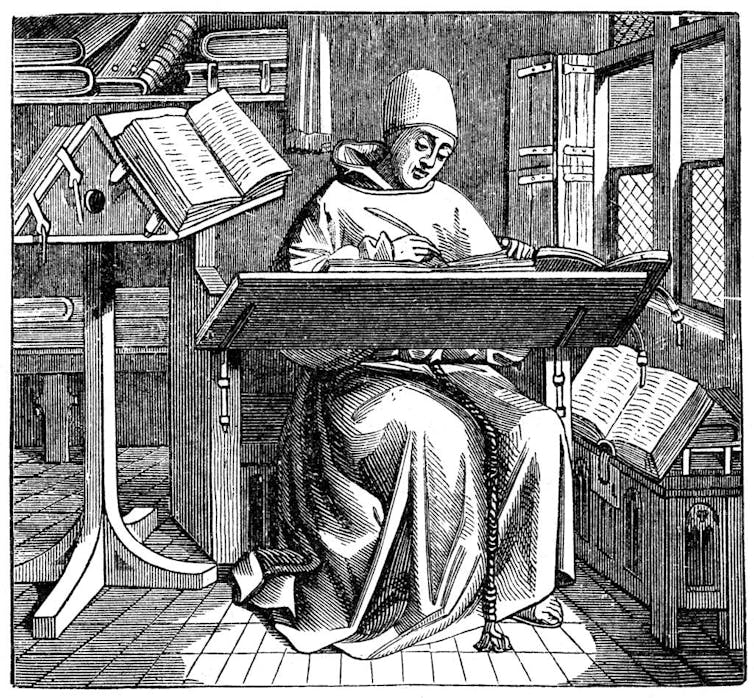

Beginning around the fifth century, monks that lived and worked in monasteries preserved ancient culture by copying and translating religious books, including the Bible, which was translated from Hebrew and Greek to Latin.

The workspaces during this time consisted mainly of a table, covered with cloth to protect the books, and a writing room, or “scriptorium” in Latin. It was common for monks to stand before their writing desks in the scriptorium – a practice that has come back into fashion with the advent of the standing desk in recent years.

Only during the Renaissance did the chair-and-table combination start to be seen in workspaces.

In 1560, Cosimo I de’ Medici, who later became the grand duke of Tuscany, wanted a building in which both the administrative and judiciary offices of Florence could be under one roof. So he commissioned the building of the Uffizi, which in Italian means “offices.”

The lower two floors of the Uffizi were designed as offices for the Florentine magistrates that were in charge of overseeing production and trade, as well as the administrative offices. The top floor was a loggia – an area open on one or more sides.

The Medici family grew an art collection on the top floor of the Uffizi. The loggia underwent various renovations to house statues and paintings, until it grew into a vast art collection and gallery. Today the entire building is an art museum.

Government, merchants and commerce

It wasn’t until the 18th century that buildings with dedicated office spaces were constructed.

The process started in London when the growth of the British empire required office administration. Two buildings were designed to handle paperwork and records related to office administration, the navy and the increased commerce. These included the Admiralty Office, a building for the Royal Navy and a building for the East India Company.

The Old Admiralty Office, built in 1726, housed government offices and meeting rooms, including the Admiralty Board Room. Today it is known as the Ripley Building, named after the architect who designed it.

Rebuilt in 1729, the headquarters for the East India Company is an early example of a multipurpose building with offices. An expansion of the East India House in London, the reconstruction was designed so the company could conduct public business and manage the trade of spices and other goods from Eastern trade.

The public areas within the building included a spacious hall and courtyard used as a reception for sales and meetings, with large rooms for the directors and offices for the clerks. An elite group of established clerks at the East India Company administered the growth of company commerce in London and thousands of miles away in East Asia.

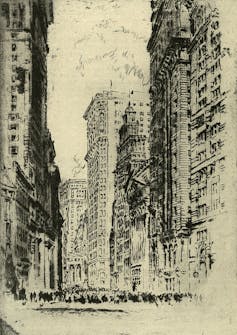

New York and the modern office

It was in the United States that the modern offices that most people are familiar with today were developed.

The number of clerks in North America increased tenfold between 1870 and 1930. At first, insurance, banking and finance sectors led the need for skilled clerks with good penmanship. Later, clerks performed specialized, though routine, tasks such as typewriting while sitting next to each other in an open office floor plan. At that point, offices grew larger and began to resemble factories.

Women’s share of clerical employment increased from 2.5% to 52.5% due to the emergence of the typewriter, drastically altering the work environment. Women entered the workforce as typists, which introduced an opportunity for independence and a break away from solely domestic responsibilities.

The Larkin Company Administration Building, a soap manufacturing facility designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1903, was one of the first modern office buildings to follow the open office floor plan.

[The Conversation’s science, health and technology editors pick their favorite stories. Weekly on Wednesdays.]

The soap company used this floor plan in New York to ensure efficiency and productivity among employees.

Skyscrapers were designed during this same period, using iron or steel frame structures borrowed from factory buildings. The advances in building technology and the open office workspaces paved the way for architects and designers in the 1950s and 1960s to develop the offices and office furniture we recognize today.

While we don’t know what the office of the future holds, we can look back at how necessity molded office space. Today the same necessity is helping us carve out workspaces in small nooks and makeshift offices.

Nicole Kay Peterson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Do special election results spell doom for Republicans in 2026?

Special election results have anticipated recent midterm outcomes. With Democrats now overperforming,…

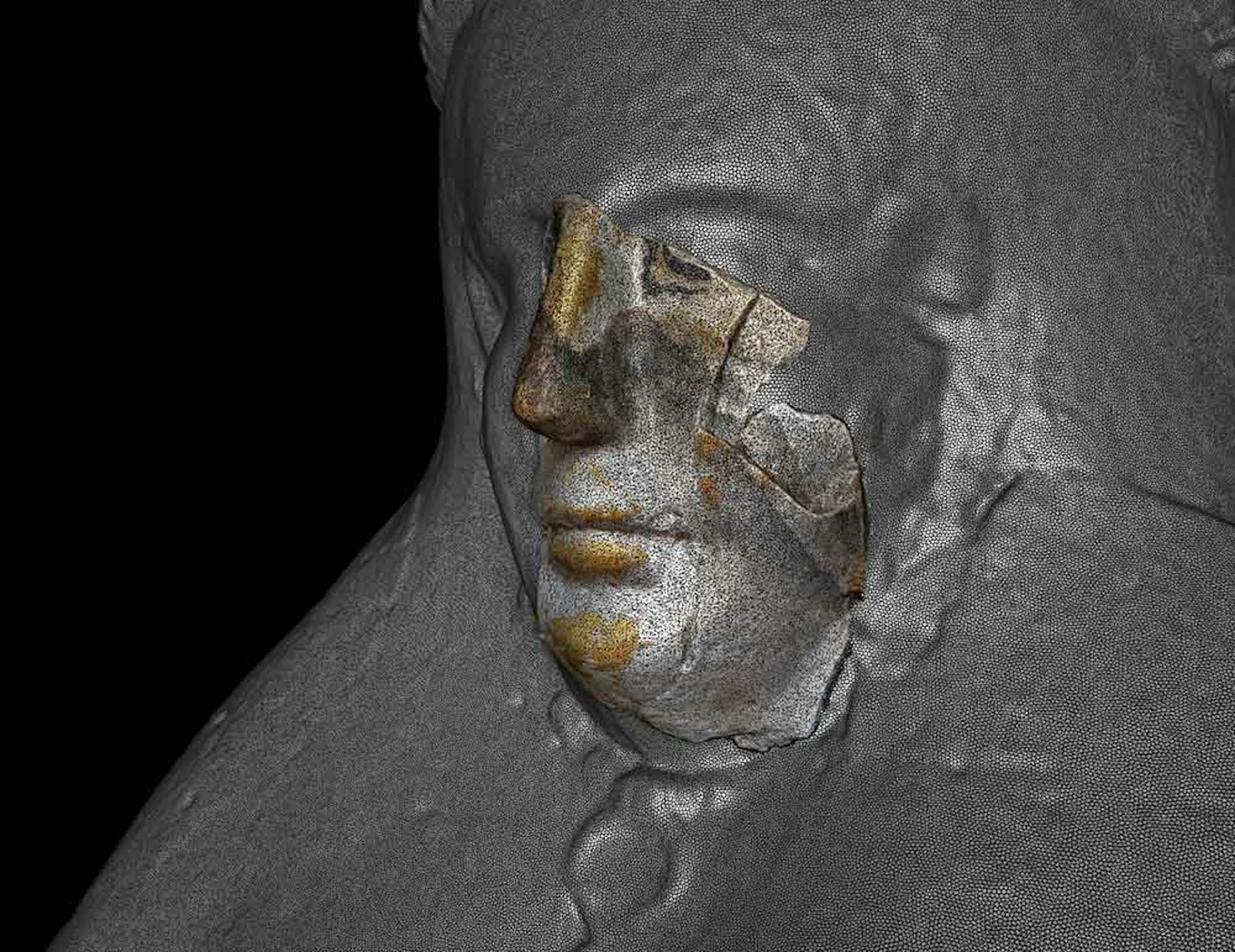

3D scanning and shape analysis help archaeologists connect objects across space and time to recover

Digital tools allow archaeologists to identify similarities between fragments and artifacts and potentially…

Trump says climate change doesn’t endanger public health – evidence shows it does, from extreme heat

Climate change is making people sicker and more vulnerable to disease. Erasing the federal endangerment…