Forced sterilization policies in the US targeted minorities and those with disabilities – and lasted

The US has a long history of forced sterilization campaigns that were driven by the bogus 'science' of eugenics, racism and sexism.

In August 1964, the North Carolina Eugenics Board met to decide if a 20-year-old Black woman should be sterilized. Because her name was redacted from the records, we call her Bertha.

She was a single mother with one child who lived at the segregated O'Berry Center for African American adults with intellectual disabilities in Goldsboro. According to the North Carolina Eugenics Board, Bertha had an IQ of 62 and exhibited “aggressive behavior and sexual promiscuity.” She had been orphaned as a child and had a limited education. Likely because of her “low IQ score,” the board determined she was not capable of rehabilitation.

Instead the board recommended the “protection of sterilization” for Bertha, because she was “feebleminded” and deemed unable to “assume responsibility for herself” or her child. Without her input, Bertha’s guardian signed the sterilization form.

Bertha’s story is one of the 35,000 sterilization stories we are reconstructing at the Sterilization and Social Justice Lab. Our interdisciplinary team explores the history of eugenics and sterilization in the U.S. using data and stories. So far, we have captured historical records from North Carolina, California, Iowa and Michigan.

Eugenics

More than 60,000 people were sterilized in 32 states during the 20th century based on the bogus “science” of eugenics, a term coined by Francis Galton in 1883.

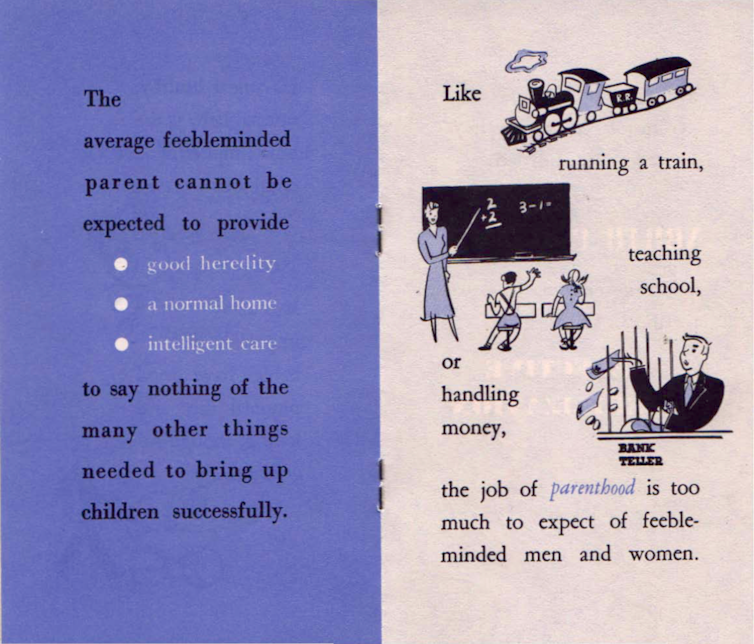

Eugenicists applied emerging theories of biology and genetics to human breeding. White elites with strong biases about who was “fit” and “unfit” embraced eugenics, believing American society would be improved by increased breeding of Anglo Saxons and Nordics, whom they assumed had high IQs. Anyone who did not fit this mold of racial perfection, which included most immigrants, Blacks, Indigenous people, poor whites and people with disabilities, became targets of eugenics programs.

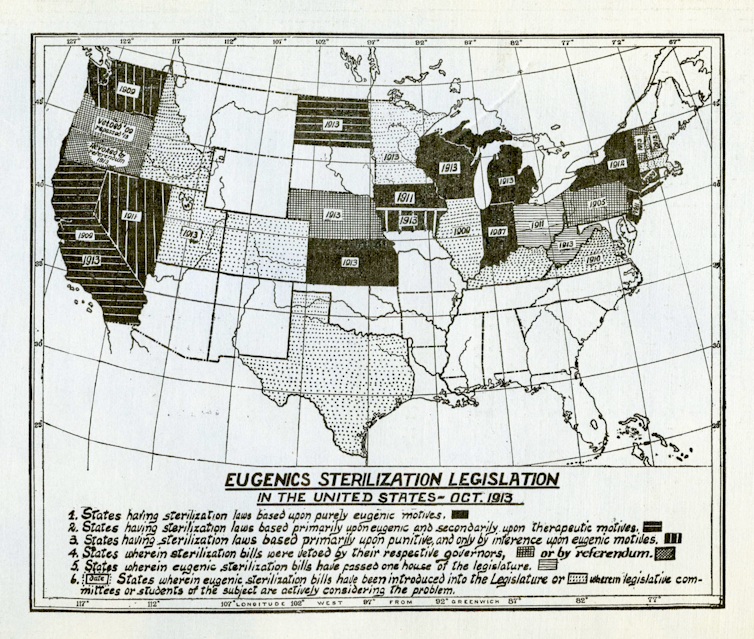

Indiana passed the world’s first sterilization law in 1907. Thirty-one states followed suit. State-sanctioned sterilizations reached their peak in the 1930s and 1940s but continued and, in some states, rose during the 1950s and 1960s.

The United States was an international leader in eugenics. Its sterilization laws actually informed Nazi Germany. The Third Reich’s 1933 “Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases” was modeled on laws in Indiana and California. Under this law, the Nazis sterilized approximately 400,000 children and adults, mostly Jews and other “undesirables,” labeled “defective.”

Anti-Black racism and sterilization

The team at the Sterilization and Social Justice Lab has uncovered some remarkable trends in eugenic sterilization. At first, sterilization programs targeted white men, expanding by the 1920s to affect the same number of women as men. The laws used broad and ever-changing disability labels like “feeblemindedness” and “mental defective.” Over time, though, women and people of color increasingly became the target, as eugenics amplified sexism and racism.

It is no coincidence that sterilization rates for Black women rose as desegregation got underway. Until the 1950s, schools and hospitals in the U.S. were segregated by race, but integration threatened to break down Jim Crow apartheid. The backlash involved the reassertion of white supremacist control and racial hierarchies specifically through the control of Black reproduction and future Black lives by sterilization.

In North Carolina, which sterilized the third highest number of people in the United States – 7,600 people from 1929 to 1973 – women vastly outnumbered men and Black women were disproportionately sterilized. Preliminary analysis shows that from 1950 to 1966, Black women were sterilized at more than three times the rate of white women and more than 12 times the rate of white men. This pattern reflected the ideas that Black women were not capable of being good parents and poverty should be managed with reproductive constraint.

Bertha’s sterilization was ordered by a state eugenics board, but in the 1960s and 1970s, new federal programs like Medicaid also started funding nonconsensual sterilizations. More than 100,000 Black, Latino and Indigenous women were affected.

Many felt shame and shrouded these experiences in secrecy, not even telling their closest relatives and friends. Others took to the streets and filed law suits to protest forced sterilization. The powerful documentary “No Más Bebés” tells the story of hundreds of Mexican American women coerced into tubal ligations at a county hospital in Los Angeles in the 1970s. One of them, who became a plaintiff in a case against the hospital, reflecting back decades later said her experience “makes me want to cry.”

Forced sterilizations continue

In the years between 1997 and 2010, unwanted sterilizations were performed on approximately 1,400 women in California prisons. These operations were based on the same rationale of bad parenting and undesirable genes evident in North Carolina in 1964. The doctor performing the sterilizations told a reporter the operations were cost-saving measures.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Unfortunately, forced sterilization continues on. Romani women have been sterilized unwillingly in the Czech Republic as recently as 2007. In northern China, Uighurs, a religious and racial minority group, have been subjected to mass sterilization and other measures of extreme population control.

All forced sterilization campaigns, regardless of their time or place, have one thing in common. They involve dehumanizing a particular subset of the population deemed less worthy of reproduction and family formation. They merge perceptions of disability with racism, xenophobia and sexism – resulting in the disproportionate sterilization of minority groups.

Alexandra Minna Stern receives funding from the National Institutes of Health-National Humane Genome Research Institute for portions of this research project.

Read These Next

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…

Iran’s targeting of airport, ports and hotels in reaction to US strikes has forced Gulf nations onto

Qatar, the UAE and other Gulf nations have spent years cultivating an image of being an oasis of stability…

‘Destruction is not the same as political success’: US bombing of Iran shows little evidence of endg

As US bombing operations in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya have shown, destruction is not the same as political…