How to stay honest when filing taxes in a pandemic year

As people file their taxes in a year where many are going through financial hardships brought on by COVID-19, a scholar argues that cheating on one's taxes would still be morally wrong.

Many in the U.S. will be filing their personal income tax returns in the next few days, as the deadline to do so was pushed from April 15 to July 15 due to the COVID-19 epidemic.

With almost half of those in the U.S. having lost at least some employment income due to the virus, the 2020 tax season may bring more personal and financial stress than usual.

As a result, there could also be a moral struggle going on about whether to be honest about one’s taxable income. Exaggerating one’s donation to Goodwill, for example, or failing to report freelance earnings could lower a taxpayer’s burden.

Each year many people do cheat on their taxes. According to findings released by the Internal Revenue Service in 2016, tax evasion costs the federal government over US$450 billion each year. The IRS estimates that for every $6 owed in taxes to the federal government, one dollar is not paid.

As a philosopher whose research focuses on character and ethics, I can say that there isn’t much controversy on this issue. Cheating is generally considered morally wrong – and that includes cheating on one’s taxes.

So, how can people stay honest this tax season?

We want to consider ourselves honest people

First let’s dive into the recent psychological research on cheating.

Researcher Lisa Shu and her colleagues published a study in 2011 in which participants were given a test with 20 problems for which they would be paid $0.50 per correct answer. Their answers were checked by a person in charge, and they were paid accordingly.

This part of the experiment was pretty straightforward. There was no opportunity to cheat.

Then the researchers changed the setup a bit. The participants were told that they would be the ones grading their answers, with no one checking on them. The financial incentive and the test remained the same. They were also told that their paperwork would be shredded and they could report their own scores.

Here’s what happened: In the first setup, participants averaged about eight correct answers. In the second setup where there was ample opportunity to cheat, the number of “correct” answers jumped to 13.22.

This finding and other published results like them provide an important lesson about the psychology of cheating: When people think they can get away with cheating, and they also think it would be worthwhile to cheat, they may well do so.

Using the same basic framework as Shu’s study, other research has since added some interesting variations to this experiment. For instance, in one study the participants were college students who first had to sign their school’s honor code before they began. Did that make any difference?

Researchers found the average number of problems solved correctly was essentially the same as when participants had no opportunity to cheat and their answers were graded by someone else.

Psychologists have provided an explanation for what is happening here. While people often want to cheat in certain cases if it would benefit them, they also want to think of themselves as honest. What the honor code did in the experiment was to serve as a moral reminder of the importance of being honest.

Other studies of cheating have found that even subtle reminders can be effective in deterring dishonest behavior. In one, from 2013, cheating continued even when the instructions said, “Please don’t cheat. … Even a small amount of cheating would undermine the study.” However, when researchers changed the wording for a second group, people did not cheat. This group was told: “Please don’t be a cheater. … Even a small number of cheaters would undermine the study.”

The switch to “cheater” called to mind how the participants wanted to think of themselves as honest. Perhaps most fascinating of all, psychologists stopped study participants from cheating simply by having them sit in front of a mirror when taking the test.

A moral reminder, in other words, makes it more difficult for most people to cheat.

What can you do to stay honest

Returning to the unique challenges facing taxpayers this year with COVID-19, the question is how people can stay honest rather than bending the truth to lessen their tax burden. Based on the research mentioned here, I would suggest three practical steps:

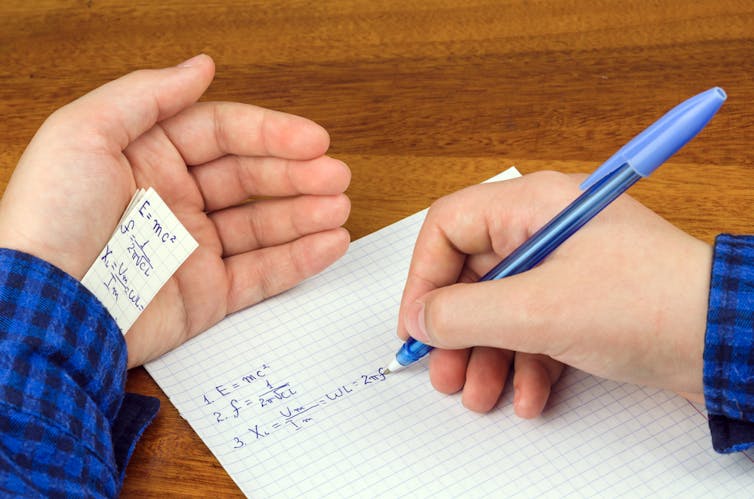

Use tangible moral reminders. They can be as simple as a Post-it Note on your computer telling you to be honest. You could also read a passage from a religious text or a different source of moral inspiration before turning to your tax returns.

If possible, do your taxes alongside someone you trust. With that accountability, it is harder to give into temptation to cheat. We want to think of ourselves as honest – and we want other people to think of us as honest, too.

Consider: What would your moral heroes in life tell you to do?

We shouldn’t cheat on our taxes, not because we necessarily care about the IRS, but because we care about being people of honesty and integrity.

This is an updated version of a piece first published on March 29, 2018.

Christian B. Miller receives funding from the John Templeton Foundation.

Read These Next

Public defender shortage is leading to hundreds of criminal cases being dismissed

There are never enough lawyers to provide indigent defense, but the situation has gotten worse since…

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…

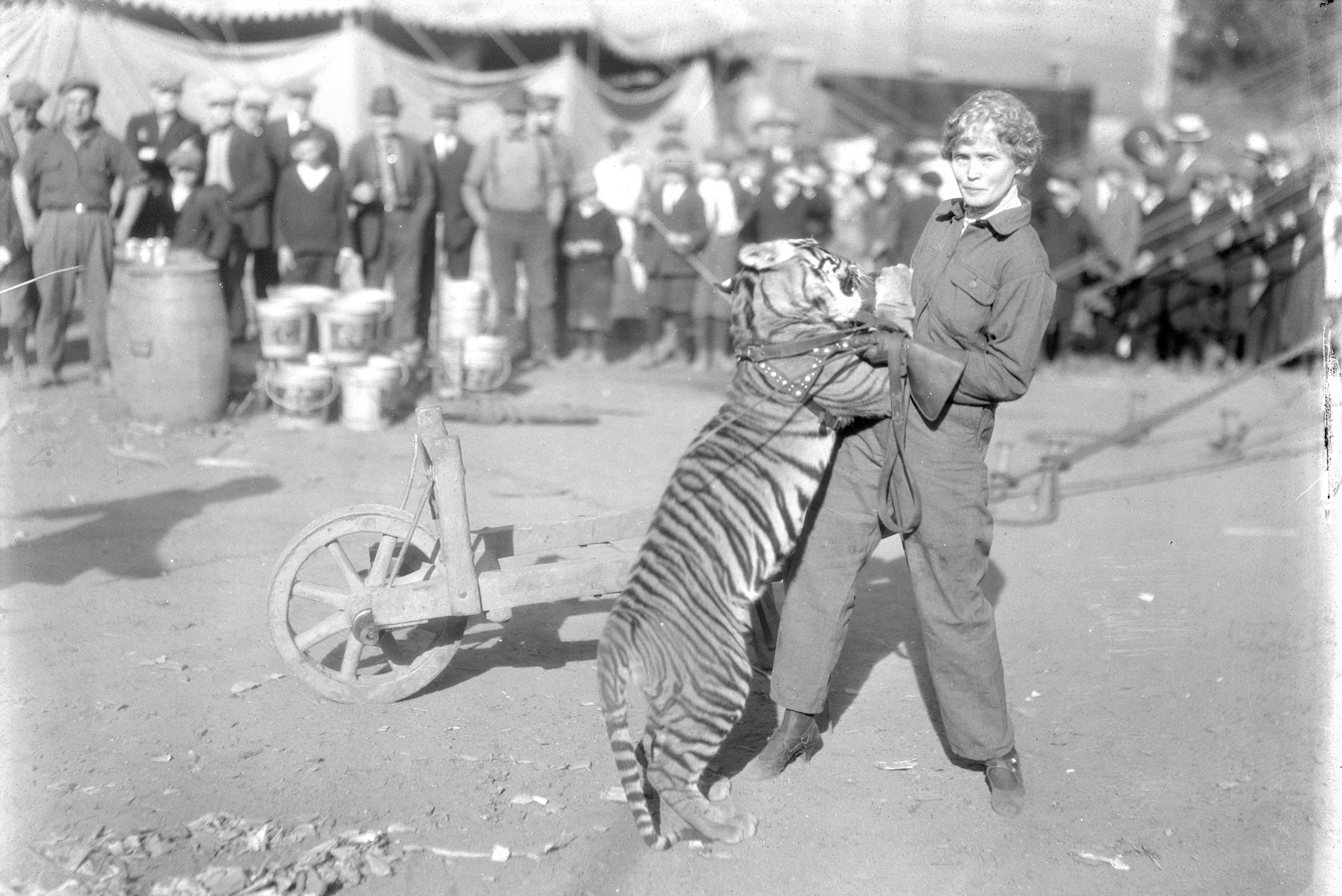

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.