Srebrenica, 25 years later: Lessons from the massacre that ended the Bosnian conflict and unmasked a

In July 1995, Serb forces murdered at least 7,000 Bosnian Muslims – an act so heinous it forced the US and UN to intervene in Bosnia's war. What has the world learned since then about ethnic violence?

Europe’s worst massacre since World War II occurred 25 years ago this July. From July 11 to 19, in 1995, Bosnian Serb forces murdered 7,000 to 8,000 Muslim men and boys in the Bosnian city of Srebrenica.

The Srebrenica massacre occurred two years after the United Nations had designated the city to be a “safe area” for civilians fleeing fighting between Bosnian government and separatist Serb forces, during the breakup of Yugoslavia.

Some 20,000 refugees and 37,000 residents sheltered in the city, protected by fewer than 500 lightly armed international peacekeepers. After overwhelming the UN troops, Serb forces carried out what was later documented to be a carefully planned act of genocide.

Bosnian-Serb soldiers and police rounded up men and boys ages 16 to 60 – nearly all of them innocent civilians – trucked them to killing sites to be shot and buried them in mass graves. Serbian forces bused about 20,000 women and children to the safety of Muslim-held areas – but only after raping many of the women. The atrocity was so heinous, that even the reluctant United States felt compelled to intervene directly in – and finally end – Bosnia’s conflict.

Srebrenica is a cautionary tale about what extremist nationalism can lead to. With xenophobia, nationalist parties and ethnic conflict resurgent worldwide, the lessons from Bosnia could not be timelier.

Perpetrators must be held accountable

Bosnia’s civil war was a complex religious and ethnic conflict. On one side were Bosnian Muslims and Roman Catholic Bosnian Croats, who had both voted for independence from Yugoslavia. They were fighting the Bosnian Serbs, who had seceded to form their own republic and sought to expel everyone else from their new territory.

The carnage that ensued is epitomized by one street in one town I visited in 1996, as part of my study of the Bosnian conflict. In Bosanska Krupa, I saw a Catholic church, a mosque and an Orthodox church on a narrow stretch of road, all left in ruins by the war. Fighters had targeted not only ethnic groups but also the symbols of their identities.

It took more than two decades to bring those responsible for the atrocities of the Bosnian civil war to justice. Ultimately, the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia, a UN court that ran from 1993 to 2017, convicted 62 Bosnian Serbs of war crimes, including several high ranking officers.

It found Bosnian Serb Army Commander General Ratko Mladić guilty of “genocide and persecution, extermination, murder, and the inhumane act of forcible transfer in the area of Srebrenica” and convicted Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić of genocide. The tribunal also indicted Yugoslav President Slobodan Miloŝević on charges of “genocide, crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva Convention, and violations of the laws or customs of war” for his role in supporting ethnic cleansing, but he died during his trial.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Though many other people have never been tried, the criminal indictments that followed Srebrenica show why the perpetrators of wartime atrocities must be held accountable, no matter how long it takes. Criminal convictions provide some closure for victims’ families and remind the guilty they can never be certain of escaping justice.

It also emphasizes that guilty individuals must be held accountable after war – not entire populations. “The Serbs” didn’t commit genocide. Members of the Bosnian Serb Army and Serbian paramilitaries, led by men like Mladić, did the killing.

Denialism is dangerous

Despite the landmark international convictions and painstaking documentation of the crimes against humanity that occurred in Bosnia, some in Serbia still claim the genocide never happened.

Using arguments similar to those made by deniers of the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust, Serbian nationalists insist the number of dead is exaggerated, the victims were combatants, or that Srebrenica is but one of many atrocities committed by all parties to the conflict.

During wartime, it is true, belligerents on both sides will do terrible things. But evidence from Bosnia clearly demonstrates that Serb forces killed more civilians than combatants from other groups. At least 26,582 civilians died during the war: 22,225 Muslims, 986 Croats and 2,130 Serbs. Muslims made up only about 44% of Bosnia’s population but 80% of the dead. The Hague tribunal convicted only five Bosnian Muslims of war crimes.

In 2013, the president of Serbia apologized for the “crime” of Srebrenica, but refused to acknowledge that it was part of a genocidal campaign against Bosnian Muslims.

Indifference is complicity

Srebrenica is a stark warning that any effort to divide people into “them” and “us” is cause for grave concern – and, potentially, for international action. Research shows that genocide starts with stigmatization of others and, if unchecked, can proceed through dehumanization to extermination.

Srebrenica was the culminating event in a yearslong campaign of genocide against Bosnian Muslims. In 1994, over a year before the massacre, the U.S. Department of State reported that Serb forces were “ethnically cleansing” areas, using murder and rape as tools of war and razing villages.

But the Clinton administration, fresh from a humiliating failure to stop a civil war in Somalia, wanted to avoid involvement. And the United Nations refused to authorize more robust action to halt Serb aggression, believing it needed to remain neutral for political reasons. It took the slaughter in Srebrenica to persuade these international powers to intervene.

Acting sooner could have saved lives. In my 1999 book, “Peacekeeping and Intrastate Conflict,” I argued that only a heavily armed force with a clear mandate to halt aggression can end a civil war.

The U.S. and UN could have supplied that force, but they dithered.

Massacres continue

Remembering past genocides like Srebenica will not prevent future ones. Marginalized groups have been brutally persecuted in the years since 1995, including in Sudan, Syria and Myanmar. Today, the Uighurs – a Muslim minority in China – are being rounded up, thrown into Chinese concentration camps and forcibly sterilized.

Nonetheless, remembrance of past atrocities is critically important. It allows people to pause and reflect, to honor the dead, to celebrate what unites humanity, and to work together to overcome their differences. Remembering also preserves the integrity of the past against those who would revise history for their own ends.

In that sense, commemorating Srebrenica 25 years later may, in some small measure, make us more willing to resist the evil of mass murder going forward.

Tom Mockaitis received a USIP grant in 1995 to fund research on the book "Peacekeeping and Intrastate Conflict: The Sword or the Olive Branch?" (Praeger, 1999), which has a chapter on the Bosnian Conflict. Some small DePaul grants and paid leave also supported his book project.

Read These Next

CIA agents successfully executed a plan for regime change in Iran in 1953 – but Trump hasn’t reveale

A covert US campaign in the mid-20th century helped steer Iran toward the intense anti-American sentiment…

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…

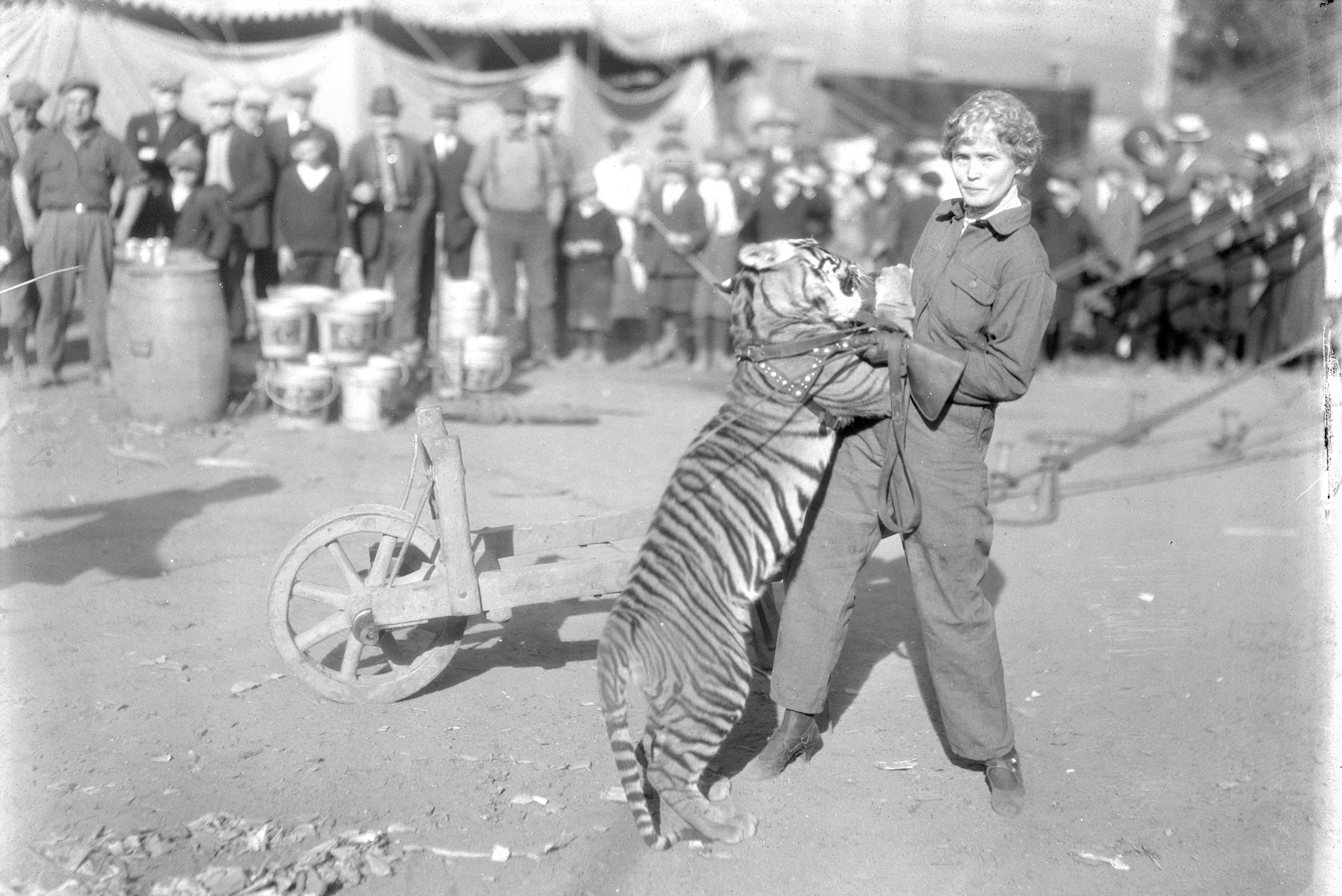

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.