Long before face masks, Islamic healers tried to ward off disease with their version of PPE

From magic bowls to holy shirts, Muslim cultures used various devices to protect the user from harm starting in the 11th century. Many of these objects were beautifully designed, too.

Just as many now don face masks and do breathing exercises to protect against COVID-19 – despite debate around the science behind such practices – so too did the Islamic world turn to protective devices and rituals in premodern times of trouble.

From the 11th century until around the 19th century, Muslim cultures witnessed the use of magic bowls, healing necklaces and other objects in hopes of warding off drought, famine, floods and even epidemic diseases.

Many of these amulets and talismans are beautifully crafted objects, and so are of interest to art historians such as myself. And while they are now largely seen as relics of folk belief and superstition, in the premodern era these ritual objects emerged from elite spheres of Islamic knowledge, science and art.

Islamic personal protective gear

The phrase “personal protective equipment” – or “PPE,” in hospital lingo – has become part of our daily lives as we watch frontline health workers don gowns, face shields and gloves to protect themselves from COVID-19.

Before the germ theory of disease, in Islamic lands epidemics were often conceptualized as a pestilential corruption of the air, through which “humid” spirits entered the human body. Some medieval Islamic thinkers also thought the plague was caused by black angels shooting invisible arrows.

The Arabic language still reflects this historic understanding of disease as an invading enemy: The term for “plague” – ta‘un – derives from the verb “ta'ana,” to pierce or strike.

Protecting its wearer against a range of assaults, the quintessential premodern Islamic PPE was the talismanic shirt – a cloth garment inscribed with holy text and often worn in warfare. Featuring circular designs on the chest, shoulder pad roundels and a fringed lapel, the talismanic shirt may sound like something out of the disco era – but in practice it more closely recalls the body armor of war.

Covered in squares, numbers and designs, the shirts were “amuletically charged,” meaning they were thought capable of physically protecting the wearer against disease and death.

One group of South Asian talismanic shirts from the 15th and 16th centuries displays the entire text of the Quran as well as all God’s names. Read aloud, these names would turn the shirt into a kind of “textile rosary,” according to religious studies researcher Rose Muravchick, allowing its owner to recite a pious litany in God’s honor.

Other talismanic shirts, from India, included a protective panel on the back inscribed with a Quranic verse calling God “the Best Guardian and the Most Merciful of the Merciful Ones.”

Anti-plague design

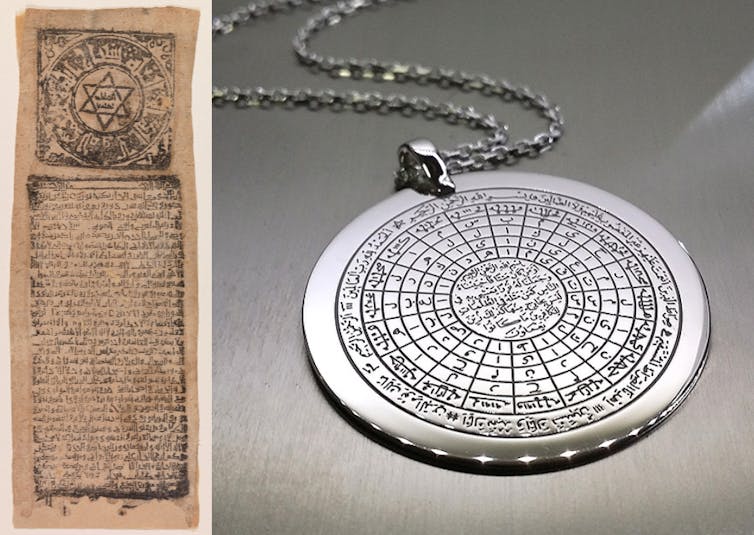

Other common medieval Islamic PPEs included the miniature talismanic scroll – a tiny roll of Quranic verses on affordable block-printed paper – and amuletic designs like the six-pointed seal of Solomon.

Quranic scrolls and amulets were worn around the neck or otherwise attached to the body, suggesting that physical contact with the object was thought to unlock the enclosed blessings or life force, known as “baraka” in Arabic.

Perhaps most germane to today’s pandemic was the Islamic anti-plague talisman known as the “Garden of Names,” used across the Islamic world and especially popular in Ottoman lands.

The Garden of Names, or Jannat al-asma’ in Arabic, is a circular amuletic design that contains 19 letters and numbers, verses from the Quran and several names of God. Some painted images of this device show controlled smudges, suggesting that people kissed, rubbed or made potions out of the design to activate its baraka.

Healing water

Water has important healing properties in Islamic traditions, too, being associated with cleanliness and godliness. The Quran credits it as the source of “every living thing.”

Since the seventh century, Muslims visiting the holy city of Mecca, located in Saudi Arabia, have visited the Zamzam well, whose water is thought to have curative properties. There, religious pilgrims still fill flasks with the holy liquid, which is then drunk straight or mixed with other liquids into therapeutic potions.

Today, you can buy a plastic bottle of Zamzam water online for about US$14. In earlier centuries, however, Zamzam water was carried home in ceramic jugs and basins for use in ritual cleaning before a meal or prayer.

Alternatively, regular water could turn curative if a folk doctor poured it into special metal bowls decorated with talismanic words and images while praying. Some of these talismanic bowls specify the reason for their creation, so historians know they were used to heal everything from poison and dog bites to intestinal problems, “pain of the heart” – that is, heartbreak – and the plague. For centuries, Muslim women in labor were also cooled with water from these bowls.

Islamic healing today

Traditional Islamic protective and healing arts have largely ceded the way to modern medicine and technology.

But amuletic objects and homeopathic practices still exist in the Islamic world, as they do in many faith cultures across the globe. Some Muslims still use magico-medicinal bowls at home; they’re sold on eBay.

Like prayer or meditation – which can have something of a placebo effect, bringing real benefits for both mind and body – Muslims facing sickness or other crises found strength and solace in religious objects for nearly a millennium.

As art objects, too, these artifacts speak to a human desire to seek comfort and cure in creativity and design. That is a feature of today’s pandemic, too.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Christiane Gruber does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Winter Olympians often compete in freezing temperatures – physiology and advances in materials scien

While physical exertion helps athletes stay warm, sweating can lead to dehydration.

Whether it’s yoga, rock climbing or Dungeons & Dragons, taking leisure to a high level can be good f

When a hobby becomes something larger, with a focus on improving skills and developing deep knowledge,…

Federal and state authorities are taking a 2-pronged approach to make it harder to get an abortion

Four years after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling gave states the power to ban abortion, further restrictions…