The tooth fairy as an essential worker in a child's world of wonder

During this unsettling time, global leaders have assured children and adults alike that the tooth fairy, free from the risk of infection, is indeed an essential worker.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, adults and children alike have called on political leaders and health experts to address a concern: Is now a bad time to lose a tooth?

In April, the premier of Quebec, François Legault, and New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern assured worried children that the tooth fairy is, indeed, an essential worker.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, followed those assurances with a guarantee of his own. The tooth fairy, he said, is not at risk of infection.

As a professor of folklore who has researched the blurry lines between reality and fantasy in children’s worldviews, I am delighted that our leaders have not mistaken childishness for triviality. Few folkloric traditions embody the wonder of childhood more clearly than the tooth fairy. The shedding of teeth, after all, marks important developmental milestones. And children have long capitalized on the occasion as an opportunity to participate in magical rituals.

For centuries, in traditions much older than the tooth fairy customs we know today, children in Europe, Asia, Africa and Oceania have practiced myriad rituals related to losing teeth. They include reported traditions in Mongolia of wrapping a shed tooth in meat and feeding it to a dog, and crushing lost teeth in Tibet between stones and tossing the dusty remains into the wind. Greek children, meanwhile, throw teeth on roofs, while in Xinjiang teeth are sewn into the shoulders of winter coats.

Usually taught to children by their parents, these magical acts are often accompanied by traditional sayings calling on the powers that be to bring new, stronger teeth as replacements. In one widespread European tradition closely related to the 18th-century French fairy tale “La Bonne Petite Souris,” children leave their shed teeth under a pillow for a mouse who exchanges it for money.

A magical rise in popularity

Folklorists generally agree that Americans’ tooth-for-money fairy rituals, possibly derived from European variants, arose around the turn of the 20th century. Like candy on Halloween, however, the tooth fairy was not a nationwide custom until the 1950s.

We can only hypothesize about the economic and cultural forces that propelled the tooth fairy’s rise to stardom, but possible causes include changing cultural attitudes toward parenting, postwar affluence and a rising number of literary and film portrayals of fairies.

In the 21st century, the tooth fairy is clearly a mainstay of popular and folk culture, but tooth fairy practices differ greatly. For example, one study suggests that Jewish children are less likely to believe in the tooth fairy than Christian children. Some children write letters to the tooth fairy, while other families have the tooth fairy leave letters encouraging dental hygiene.

Many children, of course, place their teeth under their pillows hoping the fairy will replace it with money while they sleep. But just last semester, an insightful undergraduate student at Indiana University shared an interesting variation with me. The student reported that she placed her lost teeth in a cup of water and left it on the kitchen counter. Over the span of a few days, the tooth fairy would fill the cup with a few coins each night until the tooth finally disappeared. Only then could she retrieve her money.

Placing the shed tooth in water is a custom in other parts of the world, most famously in Norway, but the origins of my student’s familial custom remain murky. After interviewing her relatives, she learned that her grandfather may have simply created their tooth-in-water tradition when he became bored with searching around under a pillow in the dark. Such is the nature of the search for folkloric origins.

Some have suggested that the tooth fairy introduces children to the capitalist ethos of American culture. I’m not so sure. Considering adults’ central role in tooth fairy customs, it seems just as likely that the tooth fairy grants grownups, for a just little while, reemergence into a child’s magical world. If I’m right about that, it’s no wonder that our leaders have deemed the tooth fairy’s work to be essential during this unsettling time.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Brandon Barker ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son poste universitaire.

Read These Next

Housing First helps people find permanent homes in Detroit − but HUD plans to divert funds to short-

Detroit’s homelessness response system could lose millions of dollars in federal funding for permanent…

When unpaid cooking, cleaning and child care get a dollar value, income inequality in the US shrinks

Women’s unpaid work at home has declined much more than men’s contributions have increased.

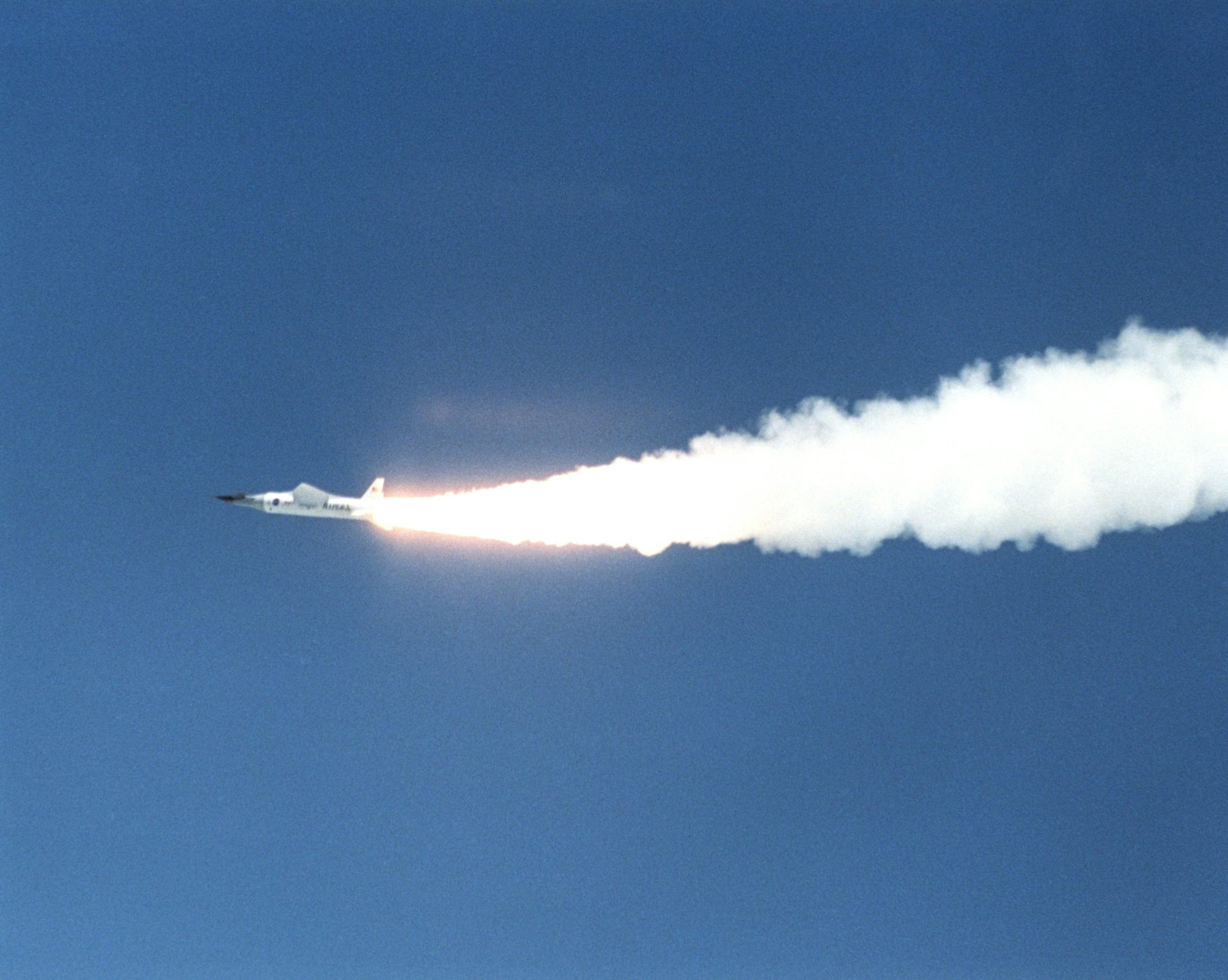

With Artemis II facing delays, NASA announces big structural changes to the lunar program

Artemis II has been plagued by similar issues to those faced by its predecessor, leading NASA to shake…