Mexican Mennonites combat fears of violence with a new Christmas tradition

Chronic violence was dampening the holiday spirit in Chihuahua, Mexico. So the Mennonite community planned a 'Parade of Lights' and holiday party where neighbors could celebrate safely even at night.

Mennonites in Mexico are promoting a bright new Christmas tradition – one born of somber origins.

The “Parade of Lights,” a nighttime procession of decorated vehicles and holiday party held this year on Dec. 7, was created by the Mennonite Museum in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua to give local people – both Mennonite and Mexican alike – a safe, family-friendly way to celebrate Christmas amid growing violence.

Drug cartels often battle for control over Chihuahua, which lies along the U.S. border. In 2010, the deadliest year on record, the state had 6,421 murders. Crime then dropped for several years but is now rising sharply. Between 2014 and 2018, murders in Chihuahua increased 70%, from 1,758 in 2014 to nearly 3,000 in 2018.

Living in rather closed Christian communities, as Mennonites have for a century in Mexico, cannot entirely protect them from chronic and sometimes random violence. In 2012, the wife of a Mennonite pastor in Chihuahua was killed while traveling to a funeral. In 2017, three local men were shot in the Mennonite colony where they lived.

The Parade of Lights was created in 2017 in hopes of nurturing Chihuahua’s holiday spirit despite perceptions of danger.

A new Christmas tradition

This year, organizers say, about 4,000 people gathered on Dec. 7 to watch the main event: a parade of cars and trucks decorated with snowmen, presents, reindeer and nativity scenes. The procession starts in the Chihuahuan city of Cuauhtémoc, drives slowly down a normally busy highway, and ends at the Mennonite Museum eight miles away.

Antonio Loewen, the Mennonite Museum’s former director, created the holiday parade in 2017 as a way to “lift up [local] villages” – that is, counteract negative views that the area is cartel-ridden and dangerous.

The museum opened in 2001 in the countryside outside Cuauhtémoc, Chihuahua – home to the largest grouping of Mennonite villages in Mexico – to teach people in Mexico about the Mennonite religion and culture. Cuauhtémoc is sometimes called the “City of Three Cultures” because of its Mennonite, northern Mexican and indigenous Mexican populations.

There are roughly 100,000 Mennonites in Mexico, descendants of Canadians who emigrated to Mexico almost a century ago, after World War I.

Members of this religious minority, which arose in northern Europe during the 16th century, hold beliefs similar to those of other Protestant Christians. But their lifestyle is intentionally different. Mennonites are pacifists who refuse military service. They tend to live apart from the outside world, practice adult baptism and are skeptical of technology’s encroachment on society.

While conducting research for my 2018 book on religious minorities in Mexico, I interviewed many Mennonites from Chihuahua about their beliefs and traditions. My father – a Canadian Mennonite with family in Mexico who has studied the migration of this community – served as my interpreter.

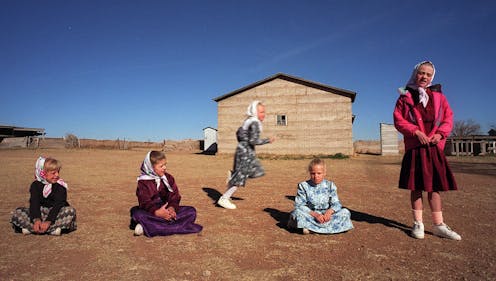

Mexican Mennonites have maintained their culture by living in rather isolated villages called colonies. Most still speak a Dutch-like language called Low German and maintain the traditional dress of head coverings and long dresses for women and overalls for men.

Some Mennonites in northern Mexico still travel by horse and buggy and limit their use of electricity. Others wear modern dress and attend Protestant churches in Spanish with their neighbors.

Cultural engagement

The Mennonite Museum and Cultural Center, which is funded by the Chihuahua state government, sees the Parade of Lights as part of its mission of outreach to the broader Mexican community.

The first year the event was held, in 2017, 3,000 people attended – vastly exceeding the 400 guests the museum expected, according to Loewen. A few local businesses and churches decorated cars to drive in the parade.

Word has spread since then.

This year, dozens of local families, churches and companies – including Quesería Dos Lagunas, one of the companies that makes the cheese Mennonites are famous for in Mexico – created floats with nativity scenes and decked out their vehicles for the parade. Afterwards, Mennonites and families from Cuauhtémoc gathered at the museum for popcorn and tamales – a traditional Christmas food in Mexico – joined by the mayor of Cuauhtémoc.

Helmut Reimer, general manager of the Microtel Inn & Suites, a local hotel that helped organize the festivities, told me he hoped the parade would “reverse” the image people have of “insecurity and ugly things” in Chihuahua.

Last year Chihuahua state had three times the number of murder as neighboring Sonora state, which has a similar population.

The Christmas parade is the latest of several local Mennonite projects in Chihuahua aimed at bringing together the peoples of northern Mexico to grapple with pervasive crime that disproportionately affects them all.

Because they traverse religious and ethnic borders, such efforts represent more than just a reaction to violence. They confirm that while Mennonites may dress, talk or pray differently than their neighbors, they are part of Chihuahua’s local community, too.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Rebecca Janzen received funding from the Plett Foundation, the C Henry Smith Peace Trust and the Kreider Fellowship at Elizabethtown College to conduct research related to this article.

Read These Next

Will AI accelerate or undermine the way humans have always innovated?

An anthropologist’s new book lays out the formula for human innovation, from stone tools to supercomputers.…

The apocrypha, Christianity’s ‘hidden’ texts, may not be in the Bible – but they have shaped traditi

‘Apocrypha’ means ‘hidden’ in Greek, but it is often used to describe texts that are outside…

Minneapolis united when federal immigration operations surged – reflecting a long tradition of mutua

Minnesotans from all walks of life, including suburban moms, veterans and protest novices, have bucked …