An ethicist explains why philanthropy is no license to do bad stuff

Giving away big sums of money is supposed to make the world a better place. So, why are so many deep-pocketed donors getting themselves and the causes they support in trouble?

I teach a course on ethics and philanthropy and have written about how to donate to charities ethically.

Recent news about people who make big charitable gifts acting badly is making me wonder whether philanthropy really does make the world better.

Think about it: Members of the Sackler family, who have given millions to arts institutions, also own Purdue Pharma. That’s the company that patented and aggressively marketed Oxycontin, an approach that helped bring about the opioid crisis. Between 1999 and 2017, close to 218,000 people died from overdoses connected to prescription opioids.

Then there’s Warren Kanders, a major donor to New York City’s Whitney Museum. He stepped down as vice chair of its board in July 2019 over his role as the chief executive of Safariland – a manufacturer of bulletproof vests, bomb-defusing robots and other security products. Artists and activists demanded his ouster after learning that Safariland made the tear gas launched at migrants at the border between Mexico and California.

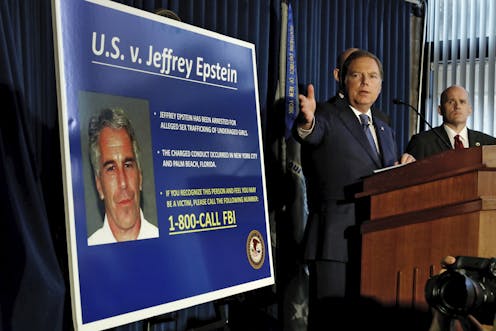

Perhaps the clearest example of doing good and also doing bad is Jeffrey Epstein. The financier, pedophile and alleged sex trafficker gave lots of money to a number of institutions, including Harvard University and MIT’s Media Lab. He made these donations before and, in some cases, after his conviction for sex crimes involving teens – although some of the charities he claimed to support say they never got the money.

Moral licensing

Is it possible that giving money away or being generous makes some people more prone to bad behavior? In a word, yes.

Studies show that people unconsciously attempt to achieve a moral balance. Social psychologists call this tendency the “moral licensing loophole.” In other words, doing good according to one’s own judgment frees people to be bad.

Although it’s not a universal experience, it is a common mental glitch. One good example is how dutiful dieters may reward themselves with a pint of ice cream. And environmentalists who go out of their way to consume less water may later use more electricity.

When people donate money to charity, others view them as generous and caring. But giving also influences how donors see themselves. It reassures them of their virtue. Here lies the trigger for moral licensing. With moral credits in hand, donors can feel entitled to be bad.

One study showed that even anticipating doing something good could be enough to trigger doing something bad. Other research shows that the good vibes from giving to one cause may allow the do-gooder to act badly in altogether unrelated ways.

Identifying real-world implications

This is a problem for nonprofits because, whether they realize it or not, they can wind up enabling donors to do bad things.

Moral licensing differs from what’s known as “reputation laundering,” in which charities help to make bad guys look like good guys by accepting their money. Reputation laundering can undermine an institution’s credibility when its donors get into trouble.

Moral licensing, however, raises questions about nonprofits facilitating harm to others through complicity.

In my view, any institution that accepts donations should help prevent the harm that moral licensing causes.

All nonprofits, whether they are big universities, little soup kitchens or anything in between, have the power to reject donations from donors when they so choose.

Certainly, vetting donors for their moral licensing risk would be a good first step for nonprofits. Among other things, it generally makes sense to exclude donors who have a clear track record of making sexist or racist remarks.

Donors have their own responsibilities and should monitor their propensity to engage in moral licensing. Rather than view their philanthropy as evidence of their personal moral virtue and a way to earn the right to do something bad, they could view it for what it is: a civic and moral duty.

Finally, donors, art lovers, artists, students, board members and employees can use their leverage to protest unscrupulous donors. The photographer and activist Nan Goldin, an artist whose work the Whitney Museum has displayed, and many employees at the MIT Media Lab have all done this, with some measures of success.

I believe that nonprofits must exercise due diligence for moral licensing before they accept large donations. This will protect their own reputations. More importantly, it will protect others from harm.

Patricia Illingworth does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Will AI accelerate or undermine the way humans have always innovated?

An anthropologist’s new book lays out the formula for human innovation, from stone tools to supercomputers.…

Fewer new moms are dying in Colorado – naloxone might be one reason why

The opioid reversal drug is distributed directly to new moms at many of Colorado’s birthing hospitals.

How natural hydrogen, hiding deep in the Earth, could serve as a new energy source

Hydrogen demand around the world is projected to grow significantly by 2050. Some of that supply could…