Should Southern Baptist women be preachers? A centuries old controversy finds new life

A controversy has erupted yet again among Southern Baptists over women's preaching. An expert explains how despite this 300-year-old controversy, Baptist women have shown remarkable leadership.

Southern Baptists are arguing again over the role women should play in the church.

Following a tweet from popular Southern Baptist speaker, teacher and writer Beth Moore that suggested she was preaching at a Southern Baptist church, many Baptist leaders accused her of defying God’s word.

These Baptist leaders believe women cannot hold positions of authority over men and that means they shouldn’t preach, teach men, or serve as pastor. The president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary went so far as to say, “I think there’s just something about the order of creation that means that God intends for the preaching voice to be a male voice.”

Beth Moore is theologically conservative and doesn’t believe women should be pastors. But her recent tweet renewed a debate that’s been an issue for more than 300 years.

The issue of women’s leadership has raged among Baptists since the beginning of the denomination in 17th century England.

Women preachers among early Baptists

As a researcher who studies Baptist women and was also ordained by Shalom Baptist Church in Louisville in 1993, I’m deeply familiar with this history.

Only a few years after Baptists arose in England, women began teaching and preaching, particularly in London.

Baptists believe God speaks directly to each individual, and, each person’s conscience, under God’s guidance, directs their belief and behavior.

Baptists also believe that each individual church is autonomous and should make its own decisions rather than relying on the authority of a bishop or pope. These core Baptist convictions led to great disagreements.

Early Baptists disagreed over, for example, whether salvation was available to everyone or only to those whom God had predestined. They even disagreed over whether or not hymn-singing was appropriate.

And, from the beginning, Baptists also disagreed on women preaching. Some congregations allowed it while others did not.

Even women who preached were not ordained. As Baptists set up processes for how churches would administer themselves, they limited ordination to men.

But some of the women justified their preaching by hearkening back to biblical times. They gave examples of the leadership of women such as Miriam, sister of Moses, who was a prophetess. They quoted an 11-century B.C. prophetess Deborah, who was a judge of the Israelites. Based on Baptist beliefs, they claimed a calling from a higher authority than church or government.

Church authorities, however, criticized and dismissed these women.

One of these women, Anne Wentworth, who was active in preaching, wrote in 1679,

“I am reproached as a proud, wicked, deceived, deluded, lying Woman; a mad, melancholy, crackbrained, self willed, conceited Fool, and black Sinner, led by whimsies, notions, and knif-knafs of my own head.”

A few Baptist churches in England permitted women to declare their commitment to Christ publicly or tell a public story of God’s work in their lives, even when they did not allow then to preach. Other churches forbade women from speaking in church at all.

Baptist women preaching in the U.S.

In the United States, the first Baptist church was founded in 1638 in Providence, Rhode Island by Roger Williams, a Puritan minister who converted to Baptist beliefs.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Baptist women continued to exercise leadership in Baptist churches in the U.S., although Baptists remained at odds over women preaching.

In the mid 18th century, two factions of Baptists emerged. One group was known as “Separate Baptists.” The group grew out of the Great Awakening, a series of revivals in the 1740s that emphasized religious feeling and zeal as important expressions of authentic faith. They “separated” from the more urban, conventional, and dispassionate “Regular” Baptists.

While Regular Baptists opposed women preaching, Separate Baptists offered greater opportunities for women. Separate Baptists accepted women as deaconesses and eldresses.

Shubal Stearns, a Congregational preacher and evangelist, became a Separate Baptist. His sister, Martha, and brother-in-law were also preachers, and together the three of them established the first Separate Baptist church in the South at Sandy Creek in 1755.

Martha Stearns Marshall soon became known for her ardent preaching. In 1810, Baptist historian Robert Semple noted about Martha’s preaching,

“Without the shadow of an usurped authority over the other sex, Mrs. Marshall, being a lady of good sense, singular piety, and surprising elocution has, in countless instances, melted a whole concourse into tears by her prayers and exhortations.”

Openness to women preaching was the exception, and women in preaching roles remained controversial.

After the Southern Baptist Convention was founded in 1845, Southern Baptist women focused their efforts mostly on supporting missions work.

Even as missionaries, they invited criticism. Southern Baptists’ most famous missionary was Lottie Moon, who was appointed as a missionary to China in 1873. Moon, who was very petite, often stood in her rickshaw and elevated her voice so she could be heard. Other missionaries accused her of “preaching.”

She responded by saying that if the men didn’t like what she was doing, they could send more men to do better.

Southern Baptist women’s ordination

Despite the controversy over women’s preaching, some churches have chosen to ordain women.

An example is the Watts Street Baptist Church in Durham, North Carolina. The church ordained the first Southern Baptist woman, Addie Davis, who had been a dean at a Baptist school in West Virginia, to ministry in 1964.

Preaching itself does not require ordination. However, ordination affirms a person’s call to ministry and allows people to perform church rituals such as leading communion and officiating at weddings. It is also a requisite for serving as pastor of a church.

After Davis, no other Southern Baptist church ordained a woman for the next seven years. Historian Elizabeth Flowers suggests that Davis’ ordination was downplayed at the time to avoid direct conflict in the denomination.

Later, as fundamentalists seized power over the Convention from more moderate Baptist leaders starting in 1979, women’s roles moved to the center of debate. Fundamentalists claim to read the Bible literally. They also insist the Bible excludes women from ordained ministry, and they saw the ordination of women as evidence of theological liberalism in the denomination.

In 1984, the Convention passed a resolution excluding women from pastoral leadership because “the man was first in creation and the woman was first in the Edenic fall.”

The Convention also amended its confessional statement in 2000 to claim, “While both men and women are gifted for service in the church, the office of pastor is limited to men as qualified by Scripture.”

Discord in the 21st century

In 2008, I published God Speaks to Us, Too: Southern Baptist Women on Church, Home, and Society. I interviewed over 150 current and former Southern Baptist women, including dozens of women in ministry.

Like their 17th century forebears, they told me that they had simply followed God’s calling. Most of them noted the refrain they had heard as children in their Southern Baptist churches: “You can be anything God calls you to be.”

Most of these women left the denomination after fundamentalists gained full control of the Convention. As more moderate Baptists abandoned the Convention and formed alternative organizations, the issue of women preaching went largely silent among Southern Baptists over the past two decades.

But with Beth Moore’s tweet, the controversy has been rekindled.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]

Susan M. Shaw does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

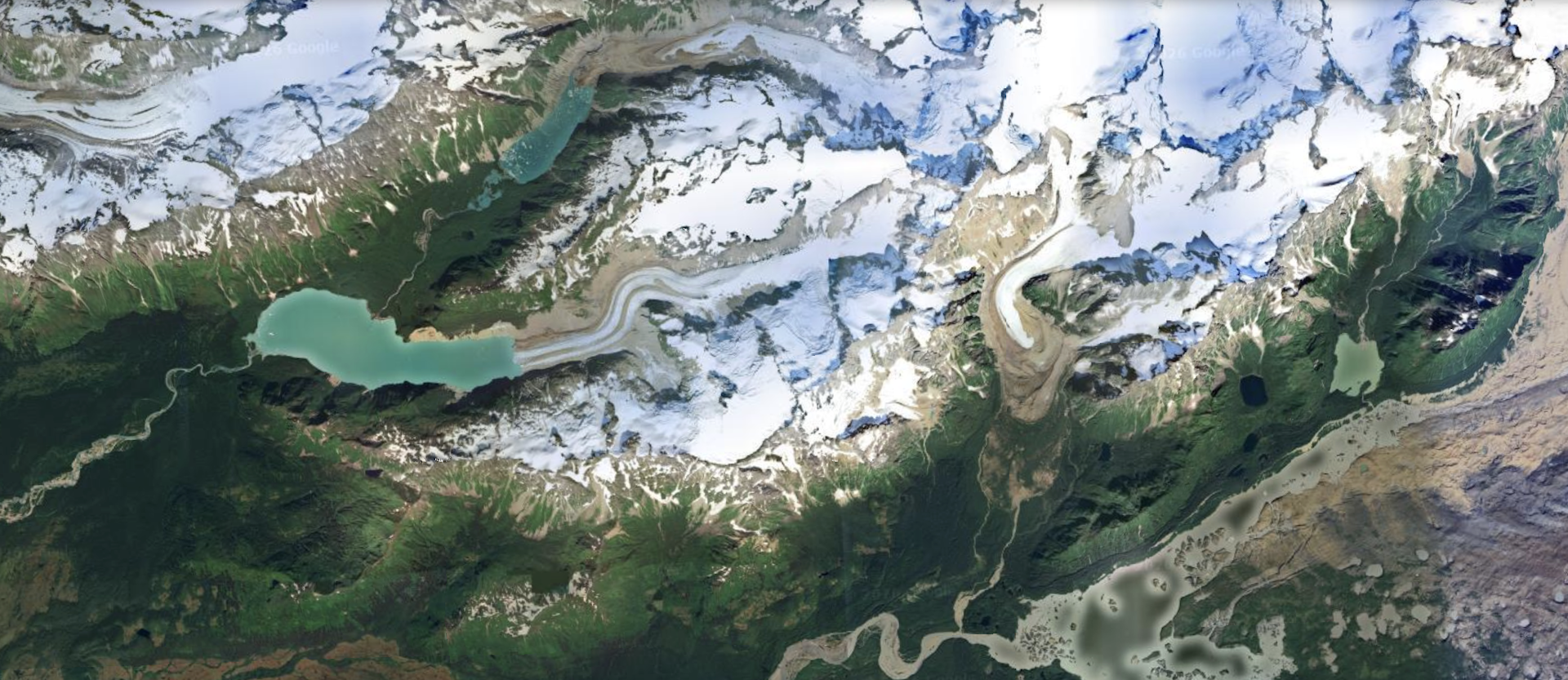

Alaska’s glacial lakes are expanding, increasing the risk of destructive outburst floods

Scientists mapped the evolution of 140 glacial lakes in Alaska and found a way to tell how much larger…

Mobile clinics offer a practical way to improve health care access in maternity care deserts

Mobile health clinics are a practical but underused solution to the growing number of maternity care…

What James Madison can teach Americans about religious freedom today

For Madison, religious freedom was not a tool for political domination. Rather, he saw it as a constitutional…