Hate crimes associated with both Islamophobia and anti-Semitism have a long history in America's pas

Crime related to Islamophobia and anti-Semitism have shown an increase in recent years. An expert explains that American antagonism toward Islamic and Jewish traditions goes back nearly 500 years

Congresswoman Ilhan Omar tweeted recently that “Islamophobia and anti-Semitism are two sides of the same bigoted coin.”

Her comments came in response to media reports that the suspect behind the shooting at a San Diego synagogue was also under investigation for burning a mosque.

Hate crimes associated with both Islamophobia and anti-Semitism have shown an increase in recent years. But is there an association between the two?

As author of “American Heretics,” I have found that American antagonism toward Islamic and Jewish traditions goes back nearly 500 years, and shares some unfortunate connections.

From time to time, Muslims and Jews have both been viewed as being antithetical to certain ideas of Americanness.

Nativism and Jewish immigration

As I explore in my book, nativism – an effort to protect the position of native-born citizens from perceived threats by immigrants – has periodically erupted in the U.S. since at least the early 19th century. These nativist beliefs have led to bias, exclusion and even violence against different religious groups who immigrated to America.

Although Jews had faced discrimination since first settling in Europe’s North American colonies in the 17th century, they were not depicted as a racial threat until around 1900.

In the early 20th century, northeastern American cities swelled in size as both factories and immigrant labor increased. Both caused popular anxieties about industrial capitalism and urban decay.

During this period – from 1870 to 1900 – the Jewish American population grew from perhaps 200,000 to over a million. That was the time when increasing numbers of immigrants were trying to escape anti-Semitism in Europe.

Nativists, however, began to portray Jews as non-whites and blamed them for bringing poverty and communism to the U.S.

In addition, American law granted citizenship only to those classified as “white” or “black.” Given anti-black sentiment, many immigrant Jews struggled to racially prove their whiteness. They did so by attempting to meet shifting legal definitions of proof, including reference to scientific authorities and skin color.

At various times, government officials classified Jews as Caucasian or Hebrew. They even seemed inclined at times to label them as Mongolians, which would exclude them from naturalization. Nativists used ugly stereotypes of Jewish physical and character traits, such as large noses and insatiable greed, in order to portray Jews as a race apart from most Americans.

During the later part of the century, such stereotypes would be applied to Muslims as well.

Anti-Semitism

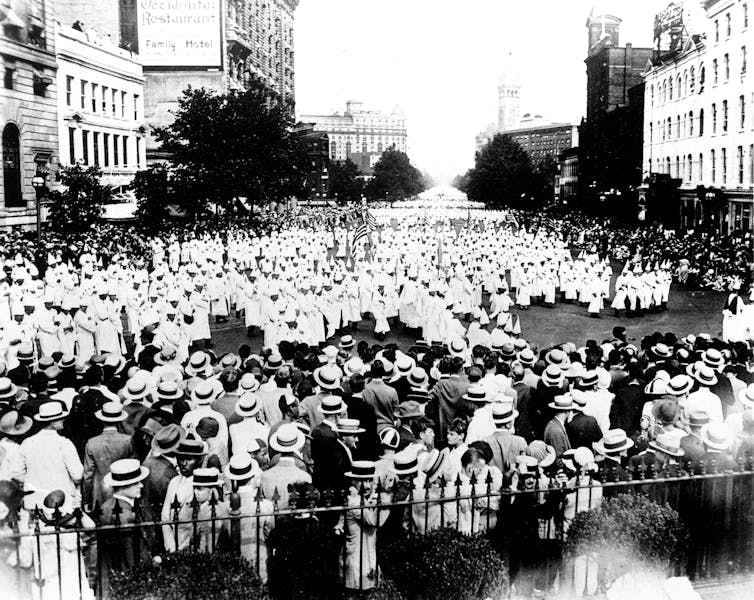

By the 1920s, the idea that Jews represented a separate, foreign race that threatened the U.S. had become prevalent among the Protestant majority. The Ku Klux Klan in that decade focused on anti-Semitism just as strongly as anti-Catholic nativism and anti-black racism.

KKK speakers and publications described Jews as unwilling to racially and culturally assimilate to an essentially white and Protestant America.

Klan membership peaked at perhaps four million throughout the nation, not simply the South. On Aug. 8, 1925, approximately 40,000 uniformed KKK members marched down Pennsylvania Avenue in a show of strength and assertiveness. Men and women wearing white caps and carrying American flags marched past a vast crowd that watched for three hours, publicly demonstrating the Klan’s strength and implicitly advocating their nativist agenda.

The organization claimed to have helped elect 75 congressmen and senators in the mid-1920s. Even future Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black was a Klan member at this time.

But it wasn’t the Klan alone. Other prominent individuals in the U.S. were also involved in spreading anti-Semitic messages.

Convinced that Jews bore responsibility for the First World War, car-maker Henry Ford sold ten million copies of his book “The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem” beginning in 1920.

Throughout the 1930s, a Catholic priest Father Charles Coughlin attracted a wide radio audience with his anti-Jewish rants. Before the Catholic Church eventually shut down his populist career in 1942, he broadcast messages of anti-Semitism, anti-capitalism and anti-communism to perhaps the largest radio audience in the world at that time as the country wrestled with the Depression.

Both Ford’s and Coughlin’s distrust of Jews rested on claims that they worked against American interests through their alleged international connections.

Popularization of Islamophobia

As with Jews, pre-existing antipathies exploded into public view when enough Muslim migrants arrived. While Muslims had been part of the U.S. since its founding, they weren’t as evident in public spaces.

Before the end of the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, as many as one African in five enslaved and brought to the U.S. was Muslim. Owners often disallowed Islamic practice and many converted slaves to Christian traditions. Hence, Americans had little awareness of their country’s Muslim heritage for a long time.

The first large-scale immigration of Muslims visible to most Americans only occurred once the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act abolished immigration quotas. Before then, racist limits restricted arrivals from all but certain European countries.

Many Americans presumed Muslims to be Arab or Turkish. Negative stereotypes portraying them as violent and hedonistic were prevalent since at least the founding of the republic.

These stereotypes, somehow, did not affect black Muslim Americans in the same manner. While law enforcement viewed some black Muslim organizations like the Nation of Islam as anti-American, they did not tend to regard them as foreign.

It was the success of Islamist ideologies challenging U.S. interests in the Middle East that sparked the latest iteration of Islamophobia.

This began in 1979, when a popular revolution involving Islamists, Marxists and others overthrew the shah of Iran, an important ally of the United States and a group of students held American embassy staff hostage for more than a year.

The success of the Islamist leader Ayatollah Khomeini in establishing an Iranian Islamic state resuscitated centuries-old fears of politics influenced by Islamic ideologies. Harassment cases against Arab and Iranian Americans went up around this time.

In the following decades, popular television shows and film depicted Arabs and Iranians as murderous and duplicitous.

These depictions merged with news coverage of “Islamic terrorists” that contributed to distrust of Muslim Americans.

Nativism, racism and Muslims

The response of many officials and other Americans to the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 helped further popularize images of Muslims based on racist and Islamophobic ideas.

With frightening frequency since 2001, gunmen have targeted individuals and communities because they “looked Muslim.” Sikhs, Hindus and others were injured or killed, as were Muslims.

In the 2008 presidential election, conservative efforts to misidentify candidate Barack Obama as a Muslim complimented efforts by various Republican congressional candidates to advance baseless allegations. False claims proliferated that Muslims sought to establish Islamic law, and build a “victory mosque” near Manhattan’s Ground Zero. The larger message was that they were anti-American.

In the years immediately following 2001 polls suggested that Islamophobic sentiment had declined. However, discrimination against Muslims remains significant, and increasing numbers of Americans have come to recognize its prevalence.

Confluence of Islamophobia and anti-Semitism

As a candidate and now as president, Donald Trump capitalized on Islamophobic sentiments. He fulfilled his campaign promise for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States” by issuing an executive order banning entry of people from seven Muslim-majority nations. The Supreme Court later upheld the ban.

But this represents only a part of a broad nativist agenda that targets various non-white Americans, and threatens Jews as well.

Trump’s lack of condemnation of the alt-right Charlottesville protesters implicitly condoned their nativist chants “The Jews will not replace us.” Some Jewish groups have worried that his own rhetoric might embolden anti-Semites, as when former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke praised President Trump.

Finding mutual concern regarding this nativist, racist language that targets their religions, a number of Muslim and Jewish leaders and communities over the past decade have found common cause and supported one another. The challenges they all face are not just political – but historical.

Peter Gottschalk does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Iraq war’s aftermath was a disaster for the US – the Iran war is headed in the same direction

More than 20 years after the US military success in Iraq, the outcome of the US effort at regime change…

US is less prone to oil price shocks than in past decades

Oil prices affect the US economy differently than in past decades. Nowadays, the US is less reliant…

What James Madison can teach Americans about religious freedom today

For Madison, religious freedom was not a tool for political domination. Rather, he saw it as a constitutional…