Nuns were secluded to avoid scandals in early Christian monastic communities

Pope Francis recently confirmed that clergy members abused nuns. Since the early days of monasticism, the presence of nuns led to restrictions that limited contact between men and women.

Pope Francis recently stated that Catholic nuns in various parts of the world, including Africa, Europe, India and Latin America, have suffered sexual abuse at the hands of priests and bishops.

In his comments during a news conference held aboard the papal plane, Pope Francis referred to a high-profile scandal within the Community of St. John – a religious congregation comprising both men and women based in France. In 2013, the Community of St. John officially confirmed allegations that its founder Marie-Dominique Philippe, who died in 2006, had engaged in “gestures contrary to chastity,” including with nuns in his spiritual care.

Such problems are certainly not new. As scholars of ancient and medieval monasticism, our research reveals that sexual contact between the sexes has been a source of anxiety – and even scandal – from the time of the earliest Christian monasteries to the present.

In many cases, scandal, or even fear of scandal, resulted in tighter restrictions on contact between religious women and men.

Women and men in the desert

Aspiring nuns and monks are required to reject private property, marriage and biological family ties. Celibacy – abstinence from sexual relations – is implicit in the rejection of marriage and procreation and has always been central to the monastic ideal.

The monastic path has not been open to celibate women on their own, however. In late antiquity and the Middle Ages, the Church generally excluded women from the priesthood. Some branches of Christianity continue this practice today. And because a priest was always needed to administer the sacraments of the Communion, penance and last rites, no woman could avoid all contact with men.

One solution was to form double monasteries, sometimes also called dual-sex, twin, or brother and sister communities. This type of community is first mentioned in written sources from fourth-century Egypt and Cappadocia, in Turkey. They still exist in various forms today.

While the exact living arrangements in the earliest double houses are not clearly explained in written sources, men and women tended to have their own quarters, divided in some cases by a river or a mountain.

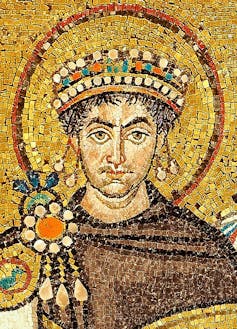

From the beginning, double monasteries attracted negative attention. In fact, many of the earliest historical sources that refer to them call for their restriction or prohibition. The sixth-century law code of the Emperor Justinian, for example, prohibited the formation of new double communities in the Byzantine Empire. He ordered that women and men be separated within communities that were already established. Sexual contact between women and men was likely the most urgent cause for concern.

The church council held in Nicaea in 787 A.D. to discuss matters of Church doctrine and practice repeated the prohibition, stating that double monasteries had become “an offense and cause of complaint to many.”

The council ruled that “monks and nuns may not reside in one building, for living together gives occasion for incontinence. No monk may enter the woman’s quarter, and no nun converse apart with a monk.”

Anxiety about contact with women

Despite such legislation, double monasteries were never entirely eliminated. When they began to appear in greater numbers during the 12th century, they triggered renewed anxiety about contact between the sexes among both clerics and laypeople.

Clerics who wrote about these double communities often enumerated the strict rules in place to limit interaction between women and men. Direct physical contact between the sexes was carefully restricted to spiritual services such as hearing confessions and celebrating the mass.

Within some communities, even brothers and sisters or mothers and sons had to get special permission to meet face to face.

The 12th-century monk Irimbert of Admont, located in what is modern Austria, claimed that his community’s women were locked within an enclosure secured with a three-lock door.

He stated that this door was only opened to admit a woman to the community, for a priest to enter to administer last rites to the dying, or to remove a nun’s body for burial.

Irimbert’s account may reflect the reality of life on the ground at 12th-century Admont, but he may also have been trying to avert criticism and deflect suspicion.

Scandal at Watton

One notorious scandal emerged during the same period in the Gilbertine Order of England. The Gilbertines organized religious houses with four subcommunities: two for women and two for men.

As the 12th-century monk Aelred of Rievaulx tells the story, a young nun at the monastery of Watton, whom he characterized as silly and lustful, conceived a child with one of the priory’s men.

When the pregnancy brought the affair to light, the nuns seized the man and forced the pregnant nun to castrate him. The nuns then shoved his severed testicles, “still stinking with blood,” into her mouth. Shortly after this horrific incident at Watton, Pope Alexander III investigated complaints made by a group of men within the broader community about the proximity of men and women in some of the order’s houses.

At least five bishops wrote to Alexander to assure him that men and women were now strictly segregated in the dual-sex Gilbertine communities within their dioceses.

As was common in the Middle Ages, Aelred laid the blame for the tragedy at Watton squarely at the feet of the nun.

Age-old restrictions

Returning to the present, however, both the current leader of the Community of St. John and Pope Francis have openly acknowledged that nuns were “preyed upon” by founder Marie-Dominique Philippe.

Among the internal “reforms” in the Community of St. John, like those in the centuries before, were measures for stricter enclosure of the community’s contemplative women.

Scholars have no witness to the lived experience of the women of Watton or the women of any of the double communities restricted by earlier legislation.

But the reforms within the Community of St. John split the women’s community and led to the departure of many of the sisters from the order. For many, as one news site reported, stricter enclosure was not in keeping with the character of the community they had chosen to enter for life. Their community was intended to be contemplative, not cloistered.

For the women who left the Community of St. John, seclusion was no longer an acceptable solution to a centuries-old problem.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Do special election results spell doom for Republicans in 2026?

Special election results have anticipated recent midterm outcomes. With Democrats now overperforming,…

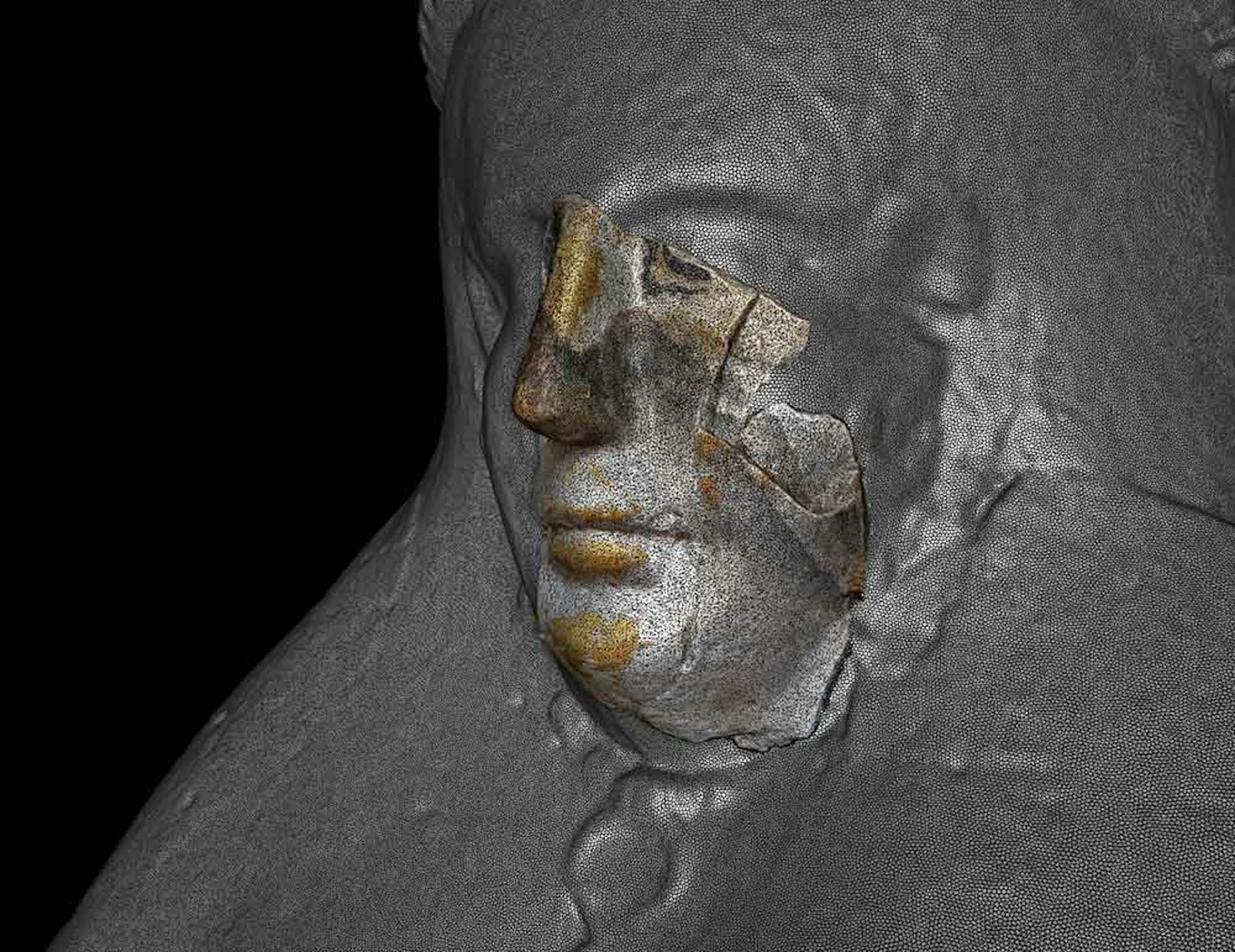

3D scanning and shape analysis help archaeologists connect objects across space and time to recover

Digital tools allow archaeologists to identify similarities between fragments and artifacts and potentially…

The intensity and perfectionism that drive Olympic athletes also put them at high risk for eating di

Athletes in sports where weight and body image come into play, such as figure skating and wrestling,…