This 19th-century argument over federal support for Christianity still resonates

President Trump has promised to protect religious liberty. But there was a time when evangelicals believed that a religion that needed protection from government had no reason to exist at all.

Since taking office, President Trump and his administration have strongly championed religious liberty, but only of a particular kind. At this week’s White House dinner for evangelical leaders, Trump emphasized that the U.S. is a “nation of believers” and promised to protect religious liberty.

Trump’s proposed policies reflect the political goals of conservative evangelicals.

At a summit last month, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a new “Religious Liberty Task Force” in the Justice Department to protect “people of faith” from “unjust discrimination” in all areas of life. Despite Sessions’ inclusive reference to “people of faith,” what was noteworthy was the presence of conservative Christians like Jack Phillips, the baker in the Masterpiece Cakeshop, who spoke at the summit.

Many critics have observed that demands for religious liberty do not extend to all religions, which prevents fair treatment. Others have noted that greater protections might harm women and LGBT Americans.

I recognize the merits of these critiques. However, largely absent from them is an equally powerful argument made over a century ago. Back then, some evangelical Christians argued that demands for government protection for Christianity signaled that their religion had failed.

The decline of Protestant influence

My research shows the late 19th century was a bad time for American Protestants. Agnosticism and atheism became popular, especially among younger intellectuals. Rising numbers of non-Protestant immigrants brought greater religious diversity.

These changes caused Protestants to lose the privileges they had enjoyed in public life, such as their control over many of the nation’s academic institutions. In one notable example, the school board in Cincinnati, Ohio, prohibited Bible reading in public schools. Catholics had objected that schools used a Protestant translation of scripture and officials agreed.

The evangelical Protestant amendment

Fearing similar cases, devout Protestants turned to the federal government. They supported an amendment first proposed during the Civil War that would have placed the language of evangelical Protestantism in the Constitution.

The amendment sought to include references to God and Jesus in the Constitution. It also declared the Bible “the supreme rule for the conduct of nations.” This final point was at odds with Catholic teaching. It made clear that the amendment was intended to placate only Protestants.

Supporters of the amendment had friends in high places. William Strong, a justice on the Supreme Court, led a group advocating its passage.

Much like Jeff Sessions, Strong urged protection for Christianity in the public sphere. The future of the religion was at stake. The justice warned that the Constitution must be made “explicitly Christian.” Otherwise, Christianity – specifically evangelical Protestantism – would be “obliterated” from the nation.

But other Protestants disagreed.

The religious critic

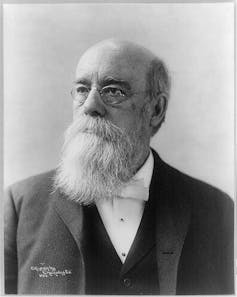

Among them was Washington Gladden. He was a minister who had grown up in a very devout family. Though he would become a leading religious liberal, Gladden was well within the mainstream of American Protestantism at the height of debates about the constitutional amendment.

In the 1870s, Gladden had great influence as religious editor of the New York Independent, one of the most read U.S. periodicals of the day. The paper had strong religious credentials. It proclaimed that in all its coverage it was “bound to the evangelical faith by the firm belief of its editors.”

The case against religious amendment

That belief, however, did not include endorsing government support of Protestantism. In his editorials, Gladden railed against the proposed amendment. The state was “not called to the inculcation or confirmation of religious truth,” he wrote.

Gladden invoked religious liberty – the same rhetoric President Trump and members of his administration have used to reassure modern evangelicals – to demand no special protection be made. Citizens should expect “equal footing for their faith, no matter what it may be,” rather than particular privilege.

Most boldly, Gladden argued that a religion that needed protection from government was a religion that had no reason to exist. He wrote on his editorial page,

“If our Christianity is of such a flimsy texture that nothing but a constitutional amendment will save it, the sooner it is obliterated the better for the land.”

Simply put, he insisted, religious people had to make their own case for their values. If they could not, they certainly did not deserve greater support. This was a controversial argument in what was largely a Protestant country, but other Protestants amplified it. Other Christian leaders came to see support for the amendment as a sign of weak faith.

A lesson for the Trump era?

Despite the backing of powerful men like William Strong, the Christian amendment failed. The nation’s Protestant leaders never came together in support of it.

While the religious critique was not the sole cause the amendment’s failure, Gladden’s line of argument was powerful. It shamed the amendment’s supporters by arguing that their demands were antithetical not only to American values but to Christian ones as well. Demands for government support only confirmed evangelical Christianity’s impotence.

History suggests it is a rhetorical strategy that critics of the Trump administration’s religious liberty policies might do well to revisit.

David Mislin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Taboo tics like shouting curses and slurs are uncommon in Tourette syndrome − but people who have th

Obscene language tics, called coprolalia, don’t reveal what people with Tourette’s think and feel.…

Why ICE’s body camera policies make the videos unlikely to improve accountability and transparency

For body cameras to function as transparency tools, wrongdoing would have to be consistently penalized,…

Artists and writers are often hesitant to disclose they’ve collaborated with AI – and those fears ma

Whether they’re famous composers or first-year art students, creators experience reputational costs…