How Catholic women fought against Vatican's prohibition on contraceptives

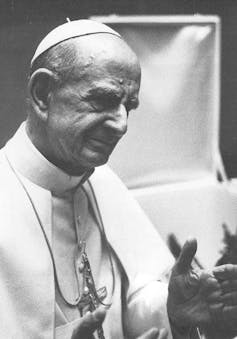

On the 50th anniversary of Humanae Vitae, an encyclical released by Pope Paul VI calling for prohibition on contraceptive use, a scholar describes the struggles of Catholic women, as well as their activism.

Fifty years ago a fierce debate erupted in the Catholic Church over the papal document “Humanae Vitae,” which reiterated the church’s ban on artificial contraception. Six hundred scholars, including many clergy, dissented from its teaching, sparking a debate that caused a crisis over authority in the worldwide church.

While much attention is focused on the epic battle between theologians and the institutional church, which undoubtedly was significant, as a historian of Catholic women, I find the responses of Catholic laywomen even more compelling.

As theologians dissented, bishops raged and popes dug in their heels, Catholic laywomen and their partners made their own family planning decisions, as they had for many years before and would for decades after.

What is Humanae Vitae?

Humanae Vitae was a papal encyclical released by Pope Paul VI in 1968. However, it wasn’t the first papal document to prohibit contraception use. Thirty-eight years prior to that encyclical, Pope Pius XI had released a document called “Casti Connubbi,” barring Catholics from using artificial contraception.

There were some clear differences between the two encyclicals. The first insisted that procreation was the chief purpose of the sexual act. The second said that the “unitive” purpose – that is, the use of sex as a means of expressing love and strengthening the marital union – was equally important.

But Paul VI ultimately insisted that the unitive could not be separated from the procreative. According to the Catholic Church, each and every conjugal act must be open to life.

Even though Humanae Vitae largely affirmed an established teaching, it was still controversial. This was because the debates among theologians and laypeople in the 30 years following Casti Connubi caused many to believe that the 1968 encyclical would overturn the Church’s ban on artificial contraception.

Role of Catholic women

What is important to note is that well before the 600 theologians expressed dissent, Catholic laywomen had already begun to reject this teaching. One major reason was what many believed to be a major flaw in the Vatican’s argument.

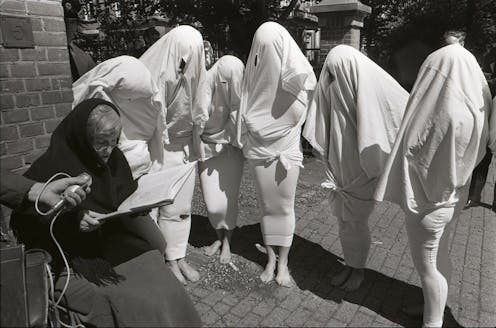

As early as the 1940s, large numbers of Catholic couples were encouraged to use the rhythm method, or timing sex to coincide with “the safe period” in a woman’s cycle, most commonly determined by charting a daily temperature reading. This was the accepted way to avoid conception, as they were not allowed to use a barrier method to achieve the same end.

Many failed to understand or accept this logic. If the church was admitting that couples could choose to limit their family size, why wouldn’t it allow them a more effective means of doing so, is what many women asked. They were also not convinced every sexual act need be open to life if the couple was open to having children.

So, starting in the 1940s, Catholic laywomen and men began to publicly discuss the church’s teaching on contraception. By the early 1960s, when the birth control pill came into common use, these questions became especially pressing. Catholic laywomen regularly wrote in the Catholic press and elsewhere expressing their views as married women and fostering a conversation that called the ban into question.

They wrote eloquently about their marriages, their sex lives, their struggles with endless pregnancies and, increasingly, their frustration with rhythm. The only method of family limitation allowed them failed over and over again while the necessity of denying themselves sex caused rifts in couples already stressed by the care of large families.

Those frustrations often included the priests who promoted rhythm. “To me and many Catholics rhythm is a manifestation of an attitude of many clergymen looking down from their pedestals, offering us glib platitudes and the letter of the law, without seeing our real problems,” wrote Carolyn Scheibelhut, an American Catholic laywoman, in a letter to the editor of the Catholic magazine Marriage, in 1964.

Did the Vatican hear laywomen’s voices?

Laywomen’s voices finally reached the Vatican through the papal birth control commission assembled by Pope John XXIII, between 1963 to 1966, to study the issue of artificial contraception.

Patty Crowley, co-founder of the Christian Family Movement and one of the few married women invited to participate, brought with her the results of a survey of Catholic couples who overwhelmingly described their struggles with the teaching, despite often heroic attempts to abide by it.

She later remarked, “It just struck me as ridiculous….How could they be talking about marriage and birth control of all things without a lot more input from the persons involved?” Crowley testified before the commission, telling them that, besides being unreliable, rhythm was psychologically harmful, did not foster married love or unity and, moreover, was unnatural.

In what was surely a first in this group of primarily celibate men, Crowley explained that the majority of women most desire sexual intercourse during ovulation, precisely when they were taught to avoid sex. “Any simple psychology book tells us that people who are in a constant state of stricture in an area that should be open and free and loving are damaging themselves and consequently others,” she insisted.

Collette Potvin, another married woman who testified, recalled thinking “When you die, God is going to say, ‘Did you love?’ He isn’t going to say, ‘Did you take your temperature?’”

Persuaded by these testimonies and others, the commission voted to overturn the ban. Leaked to the press in 1967, this decision raised the hopes of laypeople all over the world. These expectations fed the outrage when Pope Paul VI chose to disregard the majority report of his own commission in 1968.

Use of contraception today

So, do the majority of Catholic women follow the teachings of Humanae Vitae on contraceptive use?

Available data show they do not. Their choice to disregard this teaching started well before the letter was released. Among American Catholic women, for example, as of 1955, 30 percent used artificial contraception. Ten years later, that number had reached 51 percent, all before the ban was reiterated in 1968.

By 1970 the number of Catholic women in the U.S. using birth control hit 68 percent, and today there is almost no difference between the birth control practices of Catholics and non-Catholics in the United States. Globally, as of 2015, there is little difference between Catholic and non-Catholic regions. For example, the percentage of contraceptive use in heavily Catholic Latin America and the Caribbean was 72.7 percent, – a 36.9 percent increase since 1970 – compared to 74.8 percent in North America.

I would argue the 50th anniversary of Humanae Vitae is a moment to remember the laywomen who changed Catholic history before, during and after 1968. It was laywomen’s collective decision to disregard the teaching that truly shaped Catholics’ modern attitudes toward birth control.

Mary J. Henold is affiliated with Roanoke Indivisible.

Read These Next

Kansas revoked transgender people’s IDs overnight – researchers anticipate cascading health and soci

With invalid driver’s licenses and birth certificates, transgender people are at risk for more than…

Bad Bunny says reggaeton is Puerto Rican, but it was born in Panama

Emerging from a swirl of sonic influences, reggaeton began as Panamanian protest music long before Puerto…

Former Harvard president Summers’ soft landing after Epstein revelations is case study of economics’

Despite repeated calls for the university to revoke his tenure, the economist held onto his teaching…