Why the betrayal of Bill Cosby, Eric Schneiderman and other influential men is deeper than you think

It's not shallow to be upset by the latest scandals. Learning about the bad behavior of people we admire can harm our very sense of self.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman resigned on Monday, May 7, hours after The New Yorker published an article in which four women accused him of physical abuse.

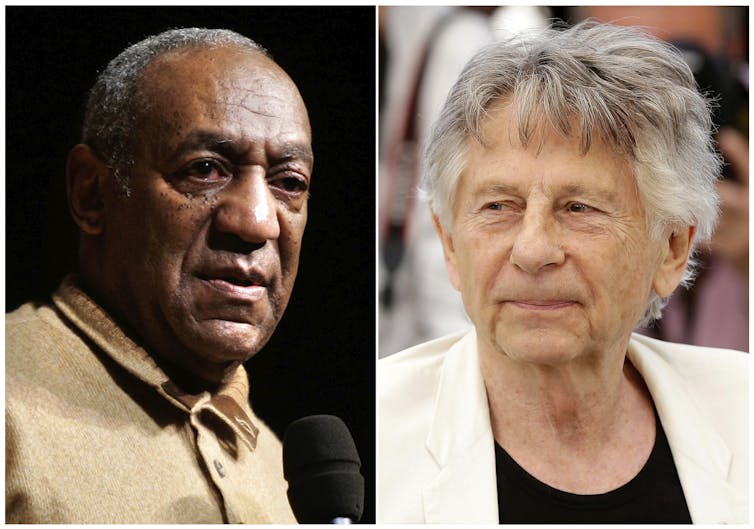

This came soon after the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences announced its expulsion of Bill Cosby and Roman Polanski for violating the organization’s standards of conduct. Cosby has been convicted of sexually assaulting a 29-year-old woman Andrea Constand in 2004, and at least 58 women have publicly accused him of sexual assault. Roman Polanski, who admitted to raping a 13-year-old in 1977, has been accused of four other child rapes.

All these men, and many others recently accused of sexual harm, carried enormous cultural influence. Indeed, the academy’s decision to expel Cosby and Polanski revived the age-old question: Can the value of a person’s creative work be separated from the harm of their behavior? As one who studies and writes on sexual violence, I believe this question fails to recognize the loss resulting from their actions. I’ll focus on Cosby since, of the three figures I have named, he has arguably been the most culturally prized.

How does a society come to terms with the knowledge that a beloved figure has committed sexual assault?

The importance of being Bill Cosby

Psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut developed the theory of “self psychology,” based on the idea that one’s sense of self develops - for better and worse - in response to external persons and things. He used the term “selfobject” to refer to those external influences that are so significant that they become a vital part of who a person is.

For Kohut, a “cultural selfobject” is an influential person whose creative work and public presence is vital to the development of selfhood for a group of people.

Cosby is a good example of a cultural selfobject. Affectionately nicknamed “America’s Dad” for his role as Cliff Huxtable on “The Cosby Show,” Bill Cosby long represented an image of fatherhood, family and upper middle-class life that both reflected and shaped what Americans valued, understood themselves to be, and saw as possible for their lives. In this way, he became part of the American self.

Practical theologian Stephanie Crumpton defines cultural selfobjects, in part, as the “public figures who mirror back our value in ways that make us feel uplifted.”

As the first black actor to star in a 1965 American TV drama series, “I Spy,” Cosby also became the first black representation of idealized American values in TV entertainment. Cosby influenced the cultural sense of self held by both white and black Americans. For some white Americans, when Cosby became a household name, he nudged their cultural sense of self beyond their whiteness. For many black Americans, Cosby mirrored back the value of black families, fathers, entertainers and communities that they had been historically denied.

The effects of betrayal

What happens when a person with such deep meaning for one’s sense of self is accused of sexual assault?

Trauma specialist Judith Herman describes the trauma of sexual violence as characterized by betrayal. Being assaulted by someone who is known and trusted shatters a survivor’s basic sense of self and world.

This traumatic betrayal ripples outward and is replicated in a diluted way for all members of a community who invested trust in the one who caused harm.

As a cultural selfobject, Cosby’s acts of violence against individual women were also a betrayal for all those who built a part of themselves in response to the value he mirrored back to them.

He cannot remain a figure who mirrors ideal American cultural values and the value of black American life because his sexual violence – behavior that undeniably rejects the value of women – is incompatible with both.

Because cultural selfobjects shape who we are, this betrayal and loss is profound. It results in a loss of a part of our own selves.

Indeed, some people could argue that accusations of sexual assault have circled publicly for decades. What’s more, Cosby’s criticism of black culture, black women and his tendency to blame black people for the impact of systemic racism on their communities has led many to feel he does not reflect their values. Over the years, this has chipped away at the degree to which he continued to function as a cultural selfobject. Nonetheless, he remained a role model for many, and so the sense of loss is ongoing.

Responding in a constructive way

The next question is, how do we respond?

Herman would say responding well to such a loss involves, at the very least, affirming, rather than denying, it happened.

As a society, acknowledging the loss that resulted from Cosby’s behavior is important because doing so also recognizes the cause. It affirms that survivors’ testimonies are worthy of belief, that sexual violence is a social harm and that it is unacceptable.

This act of internal reckoning makes solidarity more possible with immediate survivors for whom the cost of sexual violence is considerably higher. And solidarity is key for any society wanting to stop sexual violence.

Hilary Jerome Scarsella is affiliated with Into Account.

Read These Next

Kansas revoked transgender people’s IDs overnight – researchers anticipate cascading health and soci

With invalid driver’s licenses and birth certificates, transgender people are at risk for more than…

Iran will respond to US-Israeli strikes as existential threats to the regime – because they are

The latest attack on Iran goes far beyond previous operations by Israel and the US in both scale and…

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…