What 'Last Tango in Paris' teaches my students about sexual ethics

The important lessons from one of the most notorious cases of sexual manipulation took place not off-screen but right in front of the camera.

Today’s news is awash with accounts of behind-the-scenes sexual assaults involving such prominent figures as producer Harvey Weinstein, director Brett Ratner and actor Kevin Spacey. In some cases, colleagues and friends of the accused have expressed disbelief, as in the cases of popular news personalities Charlie Rose and Matt Lauer.

In my teaching of ethics at Indiana University, my students and I devote a great deal of attention to classic works in philosophy, such as the ethical writings of Plato, Aristotle and Tolstoy. But far more recent events provide ample opportunity for ethical reflection and conversation.

One of the most notorious cases of sexual manipulation took place not off screen but right in front of the camera. Its stark visibility provides an opportunity to explore darker sides of human relationships that are usually hidden from view.

‘Last Tango in Paris’

The manipulation in question took place during the filming of one of the 1970s most widely discussed and debated films, “Last Tango in Paris.”

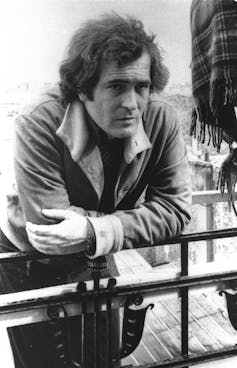

The 1972 film recounts the story of a middle-aged American hotelier whose wife has recently taken her own life. The man (portrayed by Marlon Brando) meets a young French woman (Maria Schneider), and the two begin a sexual relationship that he insists must remain anonymous.

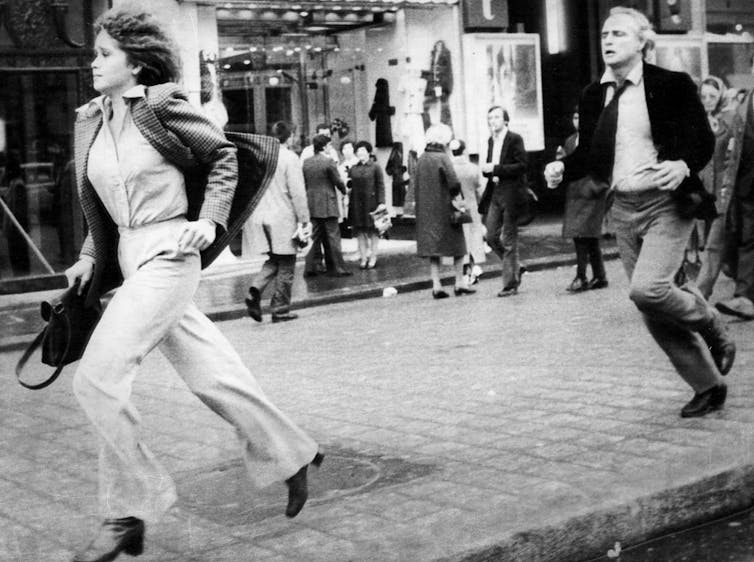

One day, the young woman returns to the site of their encounters only to discover that he has packed his things and departed unannounced. Later he returns, tells that he loves her and asks her name. She pulls a gun from a drawer, tells him her name and then shoots him. As the film ends, she is planning her testimony as a victim of attempted rape by a stranger.

The manipulation involved a simulated on-screen sexual encounter that proved all too real, in large part because Schneider was not informed about it in advance, and which she – as expected by Bertolucci and Brando – found unbearably degrading.

The film achieved notoriety in part because of its remarkably explicit portrayal of sex and sexual violence. Attempts were made in countries such as the U.K. and the U.S. to censor the film. Director Bernardo Bertolucci’s native Italy initiated criminal proceedings against him.

Not only was the film banned, but prints in Italy were seized, all copies were ordered destroyed and Bertolucci received a suspended prison sentence.

Manipulation

The relationship between actors Schneider and Brando was marked by a great imbalance of power. Schneider was 19 when the movie was filmed, while Brando was 48. He was an international star, while she was an unknown. Brando was paid US$3 million, but Schneider received $4,000.

Years after the film was released, Schneider revealed that she felt manipulated by Bertolucci. Reflecting on the experience in 2007, she told the London Daily Mail:

“Some mornings on set Bertolucci would say hello and on other days, he wouldn’t say anything at all. I was too young to know better. Marlon later said he [too] felt manipulated, and he was Marlon Brando, so you can imagine how I felt. People thought I was the girl in the movie, but that wasn’t me.”

In retrospect, she said, “I should have called my agent or had my lawyer come to the set, because you can’t force someone to do something that isn’t in the script, but at the time, I didn’t know that. Marlon said, ‘Maria, don’t worry, it’s just a movie,’ but I was crying real tears.”

The aftermath

Life after the film was difficult for Schneider.

“I felt very sad because I was treated like a sex symbol but I wanted to be recognized as an actress. The whole scandal and aftermath of the film turned me a little crazy and I had a breakdown.”

Though she starred in other films, including 1975’s “The Passenger” with Jack Nicholson, she struggled with depression and drug addiction and even attempted suicide on at least one occasion.

Throughout her subsequent career, Schneider served as an advocate for improving the experience of women in the film industry. She worked for an organization that aims to assist aging actors and directors who are down on their luck. After a career that included approximately 50 films, she died in 2011 at the age of 58.

Enduring ethical insights

Schneider’s story reveals several important lessons that deserve particular attention today, when so many reported cases of sexual manipulation occur behind the scenes.

First, although the world of screenplays, cameras and big screens may seem pure make-believe, the actors whose bodies and feelings are portrayed on film remain real. What transpires in front of the camera, as in the case of Schneider, can have enduring and sometimes devastating consequences.

Second, everyone – perhaps especially those involved in the production of news and entertainment – needs to be reminded to take personal responsibility for the protection of human dignity. The mere fact that some individuals happen to be famous, powerful or wealthy in no way absolves them of the responsibility to respect the humanity of others.

In fact, the sense of being above others is one of the most important risk factors for inhumane conduct in any sphere of life, which is why great writers since Homer have been highlighting the common humanity of people of all cultures and walks of life. Philosophers such as Plato recognized thousands of years ago how problematic it is to treat any person as a tool for another’s gratification.

As my students and I discover in our study of philosophers, the double life of Brando’s character – apparently shared by many of today’s accused abusers – is an intrinsically dangerous one, at least morally speaking. Integrity means more than observing a code of behavior. It means being the same person in all spheres of life, whether in front of the camera or behind it, in a room full of people or one-on-one.

The instant we begin to think that it is acceptable to treat people as objects – in any setting, ever – is the moment we begin to lose our moral bearings. An object is a thing, not a person, and treating someone as an object stunts the humanity of everyone involved.

Dangers of objectification

Schneider longed to revisit her decision to star in “Last Tango in Paris,” declaring that if she had the opportunity to do it over again, “I would have said no.”

Both Schneider’s experience as an actor in helping to create the film and the viewer’s experience of watching it provide powerful warnings against the dangers of objectification. Though each of us is biologically human, there is another dimension of our being that must be protected and enriched if we are to realize the full measure of our humanity.

Richard Gunderman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Kansas revoked transgender people’s IDs overnight – researchers anticipate cascading health and soci

With invalid driver’s licenses and birth certificates, transgender people are at risk for more than…

Massive US attacks on Iran unlikely to produce regime change in Tehran

President Trump has appealed to Iranians to topple their government, but a popular uprising is unlikely…

Former Harvard president Summers’ soft landing after Epstein revelations is case study of economics’

Despite repeated calls for the university to revoke his tenure, the economist held onto his teaching…