The pioneering path of Augustus Tolton, the first Black Catholic priest in the US – born into slaver

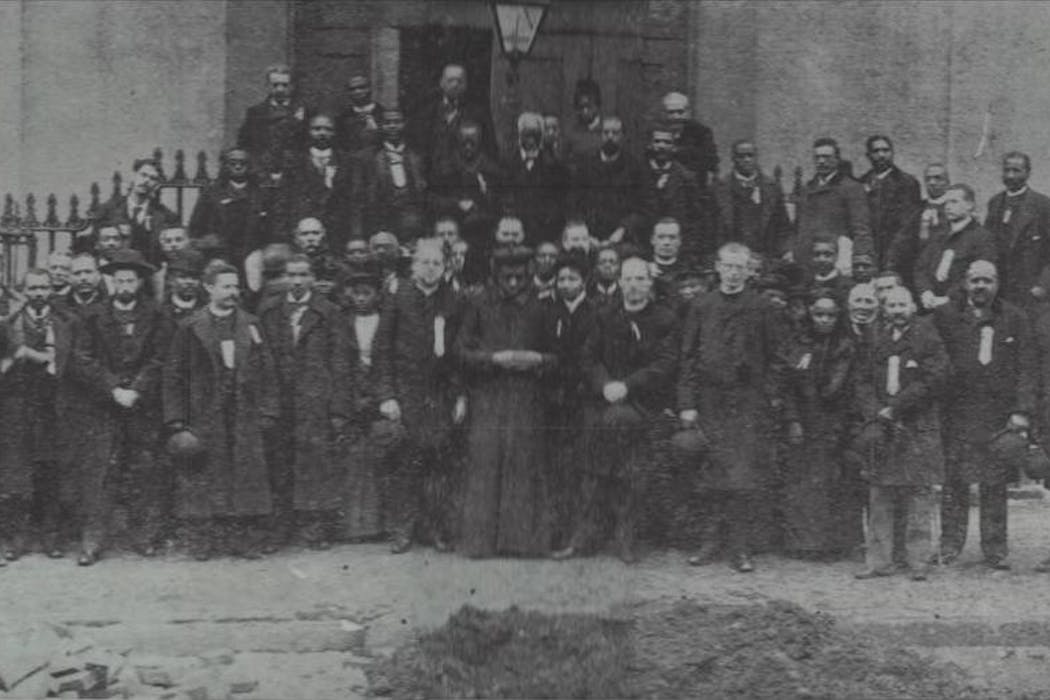

Augustus Tolton was ordained in Rome in 1886. Previously, the only Black Catholic priests in the US had been men who presented themselves as white.

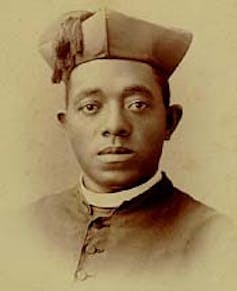

The first publicly recognized Black priest in the United States, Augustus Tolton, may not be a household name. Yet I believe his story – from being born enslaved to becoming a college valedictorian – deserves to be a staple of Black History Month. “Good Father Gus” is now a candidate for sainthood.

My forthcoming book, “The Wounded Church,” examines ways that the Catholic Church has excluded people during different chapters of its history, from women to African American people. One chapter of history that many Americans may not know about was how the U.S. church barred Black men from becoming priests – a chapter that ended with Tolton’s ordination in the late 19th century.

Slavery to seminary

Tolton was born on April 1, 1854 in Missouri, where he and his family were enslaved. He was baptized as Catholic as an infant. He escaped slavery in 1863 with his mother and siblings, eventually settling together in Quincy, Illinois.

Life in Quincy was far from a dream come true. He attempted to attend an integrated public school and a Catholic parish school, but was bullied and faced discrimination, causing him to leave. Tolton worked at a tobacco factory – the first of several manual jobs he held as a young man, while also establishing a Sunday school for Black Catholics.

Eventually, he encountered the Rev. Peter McGirr, an Irish immigrant priest who allowed the boy to attend St. Peter’s, a local parish school for white Catholics, when the tobacco factory where Tolton was employed was closed in the winter. McGirr’s decision was controversial, but Tolton pushed on and excelled. He began private tutoring by priests at Saint Francis Solanus College, now Quincy University. In 1880, he graduated as the valedictorian.

By then, it was clear that Tolton was extraordinary – even when working at a soda bottling plant, for example, he had learned German, Latin and Greek. He wanted to become a priest, yet was rejected by U.S. seminaries.

The Vatican allowed Black men to be ordained, but church hierarchy in the U.S. would not admit Black men to seminaries. Their exclusion was driven by white priests “internally beholden to the racist doctrines of the day,” as Nate Tinner-Williams, co-founder and editor of the Black Catholic Messenger, wrote in a 2021 article. Tolton applied to the Mill Hill Missionaries in London, a group that was devoted to serving Black Catholics, and was rejected by them as well.

At the time, the only Black men who were Catholic priests in the U.S. were biracial Americans who passed as white and did not openly identify themselves as Black. The most famous of these was Patrick Healy, who served as president of Georgetown University from 1873-82. Healy and his brothers were ordained in Europe.

With no route to ordination in his home country, Tolton traveled to Rome to complete his seminary education. He was ordained on Easter Saturday in 1886 and celebrated his first Mass in Saint Peter’s Basilica. He planned on going somewhere in Africa as a missionary, but was instead sent to the United States. As Tolton later recalled, “It was said that I would be the only priest of my race in America and would not likely succeed.”

‘Good Father Gus’

After ordination, Tolton returned to his home country and celebrated Masses in New York and New Jersey before settling in in his hometown of Quincy. The Masses were like a triumphant return for Tolton: filled to capacity, and drawing in people from surrounding areas to celebrate the country’s first Mass presided over by a Black priest.

“Good Father Gus” was popular, and known for being a “fluent and graceful talker” with “a singing voice of exceptional sweetness.” Yet his ministry encountered backlash – though not from parishioners. He encountered jealousy from other ministers. Tolton told James Gibbons, archbishop of Baltimore, that Black Protestant ministers were nervous that their members would leave and become Catholic. White Catholic priests “rejoiced at my arrival,” Tolton wrote, but “now they wish I were away because too many white people come down to my church from other parishes.”

Tolton’s most influential chapter began when he moved to Chicago in 1889. He was sent as a “missionary” to the Black community in Chicago, with the hope of establishing a Black Catholic church. He served the parish of St. Monica’s, described at the time as “probably the only Catholic church in the West that has been built by colored members of that faith for their own use.”

This success took a toll. Tolton had periods of sickness and took a temporary leave of absence from St. Monica’s in 1895. It is unclear whether he suffered from mental illness or physical illness. During a heat wave, he collapsed on the street. He died the next day, on July 8, 1897, at age 43.

Road to sainthood

Tolton’s legacy continues beyond his life and early death. As the first Black priest in the U.S., “whom all knew and recognized as Black,” according to Cyprian Davis, a Black Catholic monk and historian of the church, Tolton opened the doors to other Black men being ordained.

Ten years after Tolton applied to join the Mill Hill Missionaries, the order accepted a Black man for seminary and priesthood: Charles Randolph Uncles. John Henry Dorsey received the Holy Orders in 1902, becoming the second Black man ordained in the U.S. and the country’s fifth Black priest.

“Good Father Gus” is now on the path toward sainthood. In 2019, Pope Francis advanced Tolton’s cause for sainthood, making his name officially “The Venerable Father Augustus Tolton.” The next steps, beatification and canonization, require evidence of miracles, which the Archdiocese of Chicago and the Vatican are evaluating.

Today, some schools and programs carry Tolton’s name, introducing him to a new generation. But while church law and practice no longer prohibit the ordination of Black men to the priesthood, full equity in church ministry remains elusive.

Black women were long excluded from joining religious orders, and they started their own congregations in the mid-19th century. A Black man did not become a U.S. cardinal until 2020, when Wilton Gregory was named cardinal of Washington, D.C.

During Black History Month, I believe Tolton’s life and legacy offer a vital example of how one man overcame obstacles to pursue priesthood, encountering success and loneliness along the way.

Annie Selak does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

‘Hamnet’ is making audiences break down in tears – and upending beliefs about male grief

The Oscar-nominated film about Shakespeare’s son explores how men and women mourn differently –…

Kurdish gains in Syria could disappear without international support − just as they did in Iraq deca

Despite risks, Kurds in Syria have the best chance in a generation to protect their national rights.…

Legal refugees now face long detention after DHS reinterprets law on applying for a green card after

A new DHS policy could result in the detention of thousands of people who have lawful immigration status.