The 17th-century Pueblo leader who fought for independence from colonial rule – long before the Amer

Po'pay, a Tewa religious leader, led the Pueblo Revolt, the most successful Indigenous rebellion in what’s now the United States.

The U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall Collection contains 100 sculptures: two luminaries from each state. They include many familiar figures, such as Helen Keller, Johnny Cash, Ronald Reagan and Amelia Earhart. There are a few from the Colonial era, including founders such as Samuel Adams and George Washington.

Some will also be represented in the Garden of American Heroes that the Trump administration plans to build. The monument will eventually have 250 statues, and the administration has proposed a list of names. Among the figures in the Capitol who did not make the cut is Po’pay, a 17th-century Native American leader from what is now New Mexico. The inscription on his statue in the Capitol identifies him as “Holy Man – Farmer – Defender.”

As a historian of early America, I see Po’pay’s absence in the to-be-built shrine as unfortunate – but not surprising. After all, he led the Pueblo Revolt of 1680: the most successful Indigenous rebellion against colonization in the history of what became the United States. He and his followers sought political independence and religious freedom, issues central to Americans’ sense of themselves.

Spanish conquest of New Mexico

Religious movements and figures played a central role in early American history. For example, as I have frequently written, Thanksgiving is linked to Protestant religious dissenters we call Pilgrims and Puritans. American myth tells us that those hearty souls braved an ocean crossing and a contest with the “wilderness,” in the words of the Plymouth colony’s governor, William Bradford. They did so, according to our legends, to pursue their faith – though the historical record reveals that economics also drove their decision to migrate.

Po’pay, a Tewa religious leader born around 1630, did not have to cross an ocean to prove his commitment to his faith. Instead, in the face of oppression, he wanted to restore the traditions and practices of his homeland: Ohkay Owingeh, which Spanish colonizers renamed San Juan Pueblo, in what is now New Mexico. The Tewa are one of many Pueblo peoples living in the Southwest.

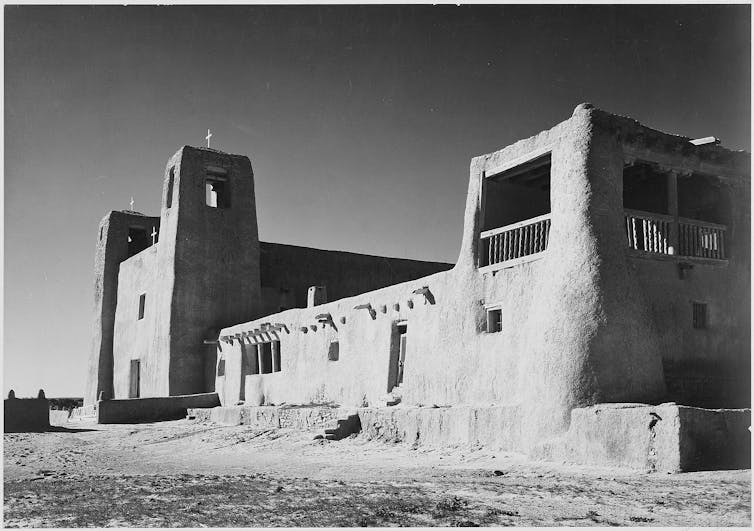

Pueblo lands had witnessed spasms of brutal violence since Spanish colonizers arrived at the end of the 16th century. In 1598, a group of Spanish soldiers arrived in Acoma, a famous Pueblo city known to the Spanish through earlier reports from the explorer Francisco Coronado. The oldest settlement within the territorial boundaries of the United States, Acoma has been occupied almost continuously since the 12th century.

At the end of the 16th century, conflict erupted when residents of Acoma refused the soldiers’ demands for food. Locals killed the commander and around a dozen others. In response, the provincial governor, Juan de Oñate, consulted with Franciscan priests and then ordered a counterattack.

The Spanish killed at least 800 residents – 300 women and children and 500 men – and perhaps as many as 1,500. In a subsequent trial, the colonizers ruled that the people of Acoma had violated their “obligations” to the Spanish king. Judges sold almost 600 survivors into slavery and amputated one foot from each man 25 or over.

In the years that followed, Spanish soldiers captured Indigenous people across the Southwest and sold them into slavery, too. For Pueblos and other Indigenous peoples, the intertwined military, political and spiritual invasions threatened seemingly every aspect of their lives.

For crown and cross

The violence at Acoma did not dissuade Spaniards eager to migrate. Around 1608, horse- and oxen-drawn carriages traveled into the territory to build a new capital, which the Spanish called Santa Fe. In addition to ferrying soldiers and farming families, those wagons also carried Franciscan friars, crucifixes, Bibles and other items the brothers needed to promote Catholicism among those they deemed to be heathens.

Over the ensuing decades, periodic conflicts pitted Indigenous peoples of various pueblos against the colonizers. Nevertheless, Spaniards erected churches in Native communities, and Franciscans often claimed that many Indigenous people welcomed their presence.

Like other Christian missionaries in the Western Hemisphere, Franciscans of the day argued that Indigenous peoples needed to abandon their traditional religions as part of the process of conversion. But many in New Mexico retained older ways. They continued to pray in chambers known as “kivas” and communicate with their deities: Pos’e yemu, for example, whom Tewas believed had the power to bring rain.

In 1675, colonial authorities accused Indigenous religious leaders of killing Franciscans with sorcery. They rounded up suspects, executed three and beat others. They also destroyed kivas. Among those imprisoned and then released was Po’pay.

Pueblo Revolt

The sting of the lash scarred more than human flesh in Pueblo communities. It fed resentment against colonists. Many of the Pueblos focused their animosity on the clerical authorities who justified the brutality of the Spanish conquest.

As the decade came to a close, the region was gripped in a drought that reduced supplies of food and water, pushing Indigenous communities’ frustrations to a tipping point. Po’pay led a rebellion that reached across Pueblo communities, saying that he was following guidance from Pos’e yemu.

On Aug. 11, 1680, Po’pay and his followers unleashed a reign of terror against Spanish soldiers, colonial farmers and Catholic churches. They systematically destroyed religious buildings, whipped statues and crucifixes, abused priests before killing them, and rendered mission bells silent by removing their clappers or drowning them in water. Far outnumbering their opponents, the Pueblos chased the colonizers to Santa Fe and then drove them out of the region.

Po’pay, according to a Native witness named Josephe, reveled in the moment, saying, “Now the God of the Spaniards, who was their father, is dead.” Historians believe that the attack killed at least 400 colonists and soldiers, or about 1 in 6 Spaniards in New Mexico. There had been 33 friars in the province before the uprising. Only 12 survived.

Against kings and coercion

In the aftermath of the Pueblos’ military victory, Po’pay led an effort to eradicate the last vestiges of Catholicism in New Mexico. He ordered that Natives who had converted needed to scrub themselves with yucca branches to remove the stain of baptism. While some churches survived, including San Estevan del Rey Mission Church at Acoma, most of the Spanish friars who had led services in them lay dead.

From 1675 to 1680, the European colonial project came under dire threat across North America. In New England, Metacom’s, or King Philip’s, War – waged between Indigenous groups and English settlers – destroyed scores of communities in one of the most destructive conflicts, measured on a per capita basis, in American history. In Virginia, a dissident hinterland landowner named Nathaniel Bacon led a revolt by aggrieved Colonists that torched the English provincial capital at Jamestown.

In this violent era, as I describe in a forthcoming book, Po’pay became one of the most consequential figures on the continent – and the embodiment of the American idea that people should be free from oppressive rulers and free, too, to practice their faith as they see fit.

Po’pay died in 1688. Four years later, Spanish colonizers returned to New Mexico and once again set out to bring the vast desert and its determined residents back under their control.

But they never erased the legacy of Po’pay, who remains a cultural hero for his defiant stand against king and cross.

Peter C. Mancall does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Why ICE’s body camera policies make the videos unlikely to improve accountability and transparency

For body cameras to function as transparency tools, wrongdoing would have to be consistently penalized,…

Honoring Colorado’s Black History requires taking the time to tell stories that make us think twice

This year marks the 150th birthday of Colorado and is a chance to examine the state’s history.

50 years ago, the Supreme Court broke campaign finance regulation

A gobsmacking amount of money is spent on federal elections in the US. The credit or blame for that…