3 states are challenging precedent against posting the Ten Commandments in public schools – cases th

New laws mandating the Ten Commandments’ display in schools have faced lawsuits in Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas.

As disputes rage on over religion’s place in public schools, the Ten Commandments have become a focal point. At least a dozen states have considered proposals that would require the posting of the Ten Commandments in classrooms, with Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas mandating their display in 2024 or 2025.

Challenges led to all three laws being at least partially blocked. Most recently, on Dec. 2, 2025, families in Texas filed a class-action lawsuit seeking to take down displays across the state. Federal trial court judges have already temporarily blocked the law in around two dozen districts. Ongoing appeals from the bills’ supporters, though, seem aimed at overturning a 45-year-old U.S. Supreme Court precedent prohibiting such displays.

As religion and education law researchers, we believe this situation is especially noteworthy because of its timing. In 2022, the Supreme Court adopted a new standard to assess religious freedom cases, which may come into play – and its judgments on religion’s role in public education are perhaps the most religion-friendly they have ever been.

The Ten Commandments and the courts

Controversy over the commandments is not new. In more than a dozen early cases, courts generally upheld laws and policies mandating their recitation in schools. These enactments survived because the Supreme Court did not extend the First Amendment to state laws until 1940.

Litigation over posting the Ten Commandments in schools first reached the Supreme Court in 1980. In Stone v. Graham, the justices invalidated a Kentucky statute requiring displays of the commandments in classrooms. The court reasoned that the law violated the First Amendment’s establishment clause: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

At the time, the court applied the first of the three criteria it has since abandoned, known as the “Lemon test,” to evaluate whether governmental action violates the establishment clause. Under this test – which developed from a 1971 Supreme Court decision – governmental actions must have a secular legislative purpose, and their main effect may neither advance nor inhibit religion. In addition, they must avoid excessive entanglement with religion.

In Stone, the justices rejected Kentucky’s argument that the displays served a secular educational purpose. The court disagreed that a small notation on posters describing the Ten Commandments as the “fundamental legal code of Western Civilization and the Common Law of the United States” was sufficient, noting that the posters were “plainly religious in nature.”

Twenty-five years later, in 2005, litigation over public displays of the Ten Commandments returned to the Supreme Court. This time, neither display was in a school.

The first dispute arose in Kentucky, where officials in two counties had erected courthouse displays including the Ten Commandments, the Magna Carta and the Declaration of Independence. The justices limited their order to one dispute, in McCreary County, invalidating the display for violating the establishment clause – largely because it lacked a secular legislative purpose.

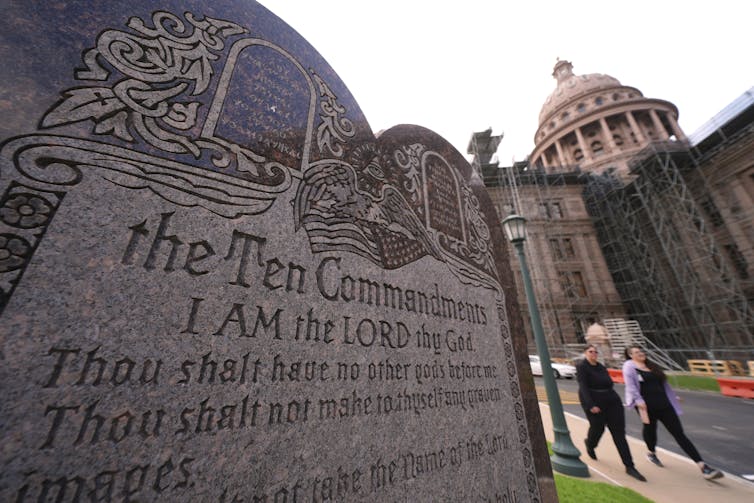

On the same day, the Supreme Court reached the opposite result in another case, Van Orden v. Perry. The court permitted a display including the Ten Commandments to remain on the grounds of the Texas Capitol in Austin, where it was one of 17 monuments and 21 historical markers.

Unlike the fairly new displays in Kentucky, the long-standing one in Texas, with the first monument erected in 1891, was built using private funds. The court left the Ten Commandments monument in place because it was a more passive display. The Capitol grounds are spread out over 22 acres, meaning the Ten Commandments were not as readily apparent as if they had been posted in classrooms.

‘Follow God’s law’

More recent controversy started in 2024. Louisiana mandated that the Ten Commandments be posted in public schools, and a federal trial court soon blocked the law. Undeterred, Arkansas and Texas passed similar legislation the following year.

Arkansas Act 573, signed into law in April 2025, obligated officials to display a “durable poster or framed copy” of the Ten Commandments in all state and local government buildings, including public school and college classrooms.

Republican Rep. Alyssa Brown, one of the Arkansas bill’s sponsors, described it as an effort to educate students on how the United States was founded and how the founders framed the Constitution.

“We’re not telling every student they have to believe in this God,” she told a legislative committee, “but we are upholding what those historical documents mean and that historical national motto.”

Texas, meanwhile, adopted a similar law in June 2025.

“It is incumbent on all of us to follow God’s law, and I think we would all be better off if we did,” the bill’s sponsor in the Texas House, Republican Rep. Candy Noble, said during debate.

Shift at SCOTUS

Supporters of these laws argue that they are constitutional because of an important shift at the Supreme Court. In 2022, the court adopted a new “history and tradition test” to assess religion in public places, including classrooms.

The “history and tradition test” originated in 2022’s Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, a case about a public high school football coach who prayed on the field at the end of games. The court ruled that school officials could not prevent the coach from praying because it was a personal religious observance protected by the First Amendment’s other religion clause: that the government shall not prohibit the “free exercise” of religion.

The Kennedy case charted a new course on religion’s place in public life. Acknowledging that it “long ago abandoned Lemon and its endorsement test offshoot,” the justices explained that “the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by ‘reference to historical practices and understandings.‘” It remains to be seen how this standard plays out.

Blocked – for now

In August 2025, a federal trial court temporarily barred officials in four school districts from enforcing Arkansas’ law. The court found that the required display would have “forced [students] to engage with” the Ten Commandments, and “perhaps to venerate and obey” them. The court also applied the new historical practices and understandings test, holding that there was no evidence of a tradition to display the Ten Commandments in public schools permanently.

The same judge later prohibited two more Arkansas school boards from posting displays.

In Louisiana, too, a federal trial court blocked a state statute. The 5th U.S Circuit Court of Appeals initially affirmed that order. However, an en banc panel of the 5th Circuit – meaning all the circuit’s active judges – will rehear the case on Jan. 20, 2026.

The Texas statute’s future is also up in the air. In August 2025, a federal trial court enjoined the law, temporarily stopping it from going into effect in 11 districts. Acknowledging the cases from Arkansas and Louisiana, the judge held that Texas’ law likely violated the First Amendment. The full 5th Circuit will hear oral arguments in January, alongside the Louisiana case.

On Nov. 18, a second federal trial court judge enjoined the Texas law in around a dozen new districts.

Religion’s role

Controversy over the Ten Commandments continues to raise larger questions over the role of religion in public education, if any.

Supporters of such bills seemingly fail to recognize that they cannot impose their religious values in the public sphere. At the same time, some opponents – including Jewish, Christian, Unitarian Universalist, Hindu and nonreligious plaintiffs – do not necessarily wish to remove religion entirely from educational institutions.

These critics want to uphold the principle that, as the Supreme Court has affirmed, the government must demonstrate “neutrality between religion and religion, and between religion and nonreligion.” In other words, critics do not want one religion or religion generally to dominate.

Today’s challenge is to find the balance in public life. We believe the courts and legislatures must avoid sending the message that religion has no place in a free and open society – just as they must not permit one set of values to dominate, as the bills in Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas seem to aspire to do.

How the courts and legislatures balance the rights of the majority and minority in these disputes over the place of the Ten Commandments in public life may go a long way toward shaping the future of religious freedom in American public education.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Sept. 5, 2025.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Why Stephen Colbert is right about the ‘equal time’ rule, despite warnings from the FCC

The ‘equal time’ rule has been around for a century and aims to promote broadcasters’ editorial…

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

Supreme Court rules against Trump’s emergency tariffs – but leaves key questions unanswered

The ruling strikes down most of the Trump administration’s current tariffs, with more limited options…