The new president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints will inherit a global faith far

The church, whose members are often known as Mormons, has grown from a small community to 17.5 million members around the world – but not without some tensions.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has spent the past few weeks in a moment of both mourning and transition. On Sept. 28, 2025, a shooting and arson at a Latter-day Saints meetinghouse in Michigan killed four people and wounded eight more. What’s more, Russell M. Nelson, president of the church, died the day before at age 101. Based on protocol, his role will most likely be filled by Dallin H. Oaks, the longest-serving of the church’s top leaders.

The next president will inherit leadership of a religious institution that is both deeply American and increasingly global – diversity at odds with the way it’s typically represented in mainstream media, from “The Secret Life of Mormon Wives” to “The Book of Mormon” Broadway musical.

As a cultural anthropologist and ethnographer, I research Latter-day Saints communities across the United States, particularly Latina immigrants and young adults. When presenting my research, I’ve noticed that many people still closely associate the church with Utah, where its headquarters are located.

The church has played a pivotal role in Utah’s history and culture. Today, though, only 42% of its residents are members. The stereotype of Latter-day Saints as mostly white, conservative Americans is just one of many long-standing misconceptions about LDS communities and beliefs.

Many people are surprised to learn there are vibrant congregations far from the American West’s “Mormon Corridor.” There are devout Latter-day Saints everywhere from Ghana and the United Arab Emirates to Russia and mainland China.

Global growth

Joseph Smith founded The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in upstate New York in 1830 and immediately sent missionaries to preach along the frontier. The first overseas missionaries traveled to England in 1837.

Shortly after World War II, church leaders overhauled their missionary approach to increase the number of international missions. This strategy led to growth across the globe, especially in Central America, South America and the Pacific Islands.

Today, the church has over 17.5 million members, according to church records. A majority live outside the U.S., spread across more than 160 countries.

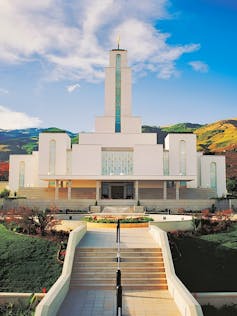

One way the church and researchers track this global growth is by construction of new temples.These buildings, used not for weekly worship but special ceremonies like weddings, were once almost exclusively located in the United States. Today, they exist in dozens of countries, from Argentina to Tonga.

During Nelson’s presidency, which began in 2018, he announced 200 new temples, more than any of his predecessors. Temples are a physical and symbolic representation of the church’s commitment to being a global religion, although cultural tensions remain.

Among U.S. members, demographics are also shifting. Seventy-two percent of American members are white, down from 85% in 2007, according to the Pew Research Center. Growing numbers of Latinos – 12% of U.S. members – have played a significant role sustaining congregations across the country.

There are congregations in every U.S. state, including the small community of Grand Blanc, Michigan, site of the tragic shooting. Suspect Thomas Jacob Sanford, who was fatally shot by police, had gone on a recent tirade against Latter-day Saints during a conversation with a local political candidate.

In the following days, an American member of the church raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for Sanford’s family.

Growing pains

Despite the church’s diversity, its institutional foundations remain firmly rooted in the United States. The top leadership bodies are still composed almost entirely of white men, and most are American-born.

As the church continues to grow, questions arise about how well the norms of a Utah-based church fit the realities of members in Manila or Mexico City, Bangalore or Berlin. How much room is there, even in U.S. congregations, for local cultural expressions of faith?

Latino Latter-day Saints and members in Latin America, for example, have faced pushback against cultural traditions that were seen as distinctly “not LDS,” such as making altars and giving offerings during Dia de los Muertos. In 2021, the church launched a Spanish-language campaign using Day of the Dead imagery to increase interest among Latinos. Many members were happy to see this representation. Still, some women I spoke with said that an emphasis on whiteness and American nationalism, as well as anti-immigrant rhetoric they’d heard from other members, deterred them from fully celebrating their cultures.

Even aesthetic details, like musical styles, often reflect a distinctly American model. The standardized hymnal, for example, contains patriotic songs like “America the Beautiful.” This emphasis on American culture can feel especially out of sync in places in countries with high membership rates that have histories of U.S. military or political interventions.

Expectations about clothing and physical appearance, too, have prompted questions about representation, belonging and authority. It was only in 2024, for instance, that the church offered members in humid areas sleeveless versions of the sacred garments Latter-day Saints wear under clothing as a reminder of their faith.

Historically, the church viewed tattoos as taboo – a violation of the sanctity of the body. Many parts of the world have thousands of years of sacred tattooing traditions – including Oceania, which has high rates of church membership.

Change ahead?

Among many challenges, the next president of the church will navigate how to lead a global church from its American headquarters – a church that continues to be misunderstood and stereotyped, sometimes to the point of violence.

The number of Latter-day Saints continues to grow in many parts of the world, but this growth brings a greater need for cultural sensitivity. The church, historically very uniform in its efforts to standardize Latter-day Saints history, art and teachings, is finding that harder to maintain when congregations span dozens of countries, languages, customs and histories.

Organizing the church like a corporation, with a top-down decision-making process, can also make it difficult to address painful racial histories and the needs of marginalized groups, like LGBTQ+ members.

The transition in leadership offers an opportunity not only for the church but for the broader public to better understand the multifaceted, global nature of Latter-day Saints’ lives today.

Brittany Romanello does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Trump says climate change doesn’t endanger public health – evidence shows it does, from extreme heat

Climate change is making people sicker and more vulnerable to disease. Erasing the federal endangerment…

Citizenship voting requirement in SAVE America Act has no basis in the Constitution – and ignores pr

The House has passed a bill to require proof of citizenship for voting. Although it likely won’t become…

How the 9/11 terrorist attacks shaped ICE’s immigration strategy

The growth of today’s aggressive immigration tactics traces back 25 years, when enforcement took on…