Muslim men have often been portrayed as ‘terrorists’ or ‘fanatics’ on TV shows, but Muslim-led story

Post 9/11, brown and sometimes Black Muslim characters were portrayed as ‘good’ only when aligned with US state power. Muslim filmmakers are trying to change that.

For over a century, Hollywood has tended to portray Muslim men through a remarkably narrow lens: as terrorists, villains or dangerous outsiders. From shows such as “24” and “Homeland” to procedural dramas such as “Law and Order,” this portrayal has seldom allowed for complexity or relatability.

Such depictions reinforce Orientalist stereotypes – a colonial worldview that treats cultures in the East as exotic, irrational or even dangerous.

However, recent years have seen a noticeable increase in Muslim-led storytelling across platforms in the U.S. and U.K. While still a minority, these stories depart from decades of misrepresentation.

As a scholar of Islam and gender who has conducted research on masculinity, sexuality and national belonging in Muslim entertainment media, I analyze a new wave of critically acclaimed shows where Muslim characters are at the center of the narrative.

Historical stereotypes

Scholar of media and race Jack Shaheen has documented the systematic vilification of Arabs and Muslims in Western media. In his 2001 book “Reel Bad Arabs,” he analyzed over a thousand films and found that the vast majority depicted Arab and Muslim men almost exclusively as fanatics, oil-rich villains and misogynists.

More recently, a 2021 study from the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative looked at 200 popular movies and found that Muslim characters were either completely missing or shown as violent.

Despite the consistency of negative representations of Muslims on television following the rise in Islamophobia, the post-9/11 climate actually saw the introduction of more diverse Muslim characters. Such portrayals promoted the idea of the U.S. as a tolerant, liberal society.

Scholar of popular culture Evelyn Alsultany writes that Hollywood introduced Muslim characters who were often law-abiding citizens or patriotic allies. She explains that despite these positive attempts, these characters were still depicted in simplistic ways, as either “good Muslims” or “bad Muslims.” The “good Muslim/bad Muslim” framework was coined by scholar of postcolonialism Mahmood Mamdani to describe how Muslims are understood across this binary. The “good Muslims” distance themselves from their faith and align themselves with Western liberal values to gain acceptance.

Expanding on this theme, Islamic studies scholar Samah Choudhury explains how the mainstream success of South Asian Muslim male comedians such as Hasan Minhaj, Kumail Nanjiani and Aziz Ansari is shaped by their adoption of secular ideals.

Even so-called “positive” characters, such as Muslim FBI agents or loyal informants in shows like “NCIS” or “Homeland,” ultimately served to normalize state surveillance and justify the global war on terrorism, a global campaign initiated by the U.S. following the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. These brown and sometimes Black Muslim characters are portrayed as “good” only when aligned with U.S. state power.

Effort in contemporary television

Hulu’s comedy drama series “Ramy” is a milestone in Muslim storytelling. Created by actor-comedian Ramy Youssef, the series, which debuted in 2019, follows a young Egyptian-American Muslim navigating family, faith and relationships in New Jersey.

Ramy is devoid of storylines about national security. Instead, the show foregrounds its main character’s grappling with religiosity, dating and identity. Moreover, as I have argued elsewhere, the protagonist’s religious devotion is never a punchline but a part of his everyday experience.

For instance, Ramy prays five times a day – at the mosque and at home, fasts during Ramadan, and abstains from alcohol as a matter of Islamic observance. At the same time, he also partakes in hookup culture and wrestles with guilt for falling short of Islamic ideals. By showcasing this duality, the show illuminates internal debates within American Muslim communities, including on gendered norms around marriage and sexual ethics.

Across the Atlantic, the BBC comedy series “Man Like Mobeen,” created by comedian-actor Guz Khan, offers a layered portrayal of Muslim life in inner-city Birmingham, England. The show follows Mobeen, a reformed British Pakistani gangster, striving and often failing to leave his criminal past behind and live as a devout Muslim while raising his teenage sister.

The show explores the struggles of the working class. It situates Muslim communities within broader class and racial dynamics whereby working-class Black and brown men are vulnerable to racial profiling by law enforcement and gang violence.

With incisive and dark humor, it challenges British racism against Muslims and offers social and political commentary on U.K. society. This includes critiques of British far-right movements and their racism, as well as the failures of the National Health Service.

Muslim women on screen

The flip side of stereotypical portrayals of Muslim men as violent and misogynist is the equally reductive portrayal of Muslim women as passive or oppressed. When Muslim women appear on screen, they are often presented as submissive or “liberated” only by a white non-Muslim male romantic interest. This process of liberation usually involves removing their hijab or distancing themselves from Islam.

A refreshing departure from such storytelling norms can be found in the British Channel 4 comedy “We Are Lady Parts,” created by filmmaker and writer Nida Manzoor, which debuted in 2021.

The show follows an all-female Muslim punk band in London. The bandmates are funny, creative and rebellious. While they defy Western views of Muslim women, they do not appear to be written solely to shatter stereotypes.

They reflect the contradictions that many Muslims live with, juggling faith, identity and politics in their music. The band’s songs include feminist themes but are diverse, subverting Islamophobic stereotypes against women with humor with songs like “Voldemort Under My Headscarf,” or lusting after a love interest in “Bashir with the good beard.”

The band members are also often seen engaged in ritual prayer together, a unified display of worship among women who otherwise have very different personalities, fashion sensibilities and goals in life. The show also addresses queerness, Islamophobia and intergenerational conflict with nuance and humor.

I explore all of these themes in further detail in my forthcoming book, in which I examine how this new wave of Muslim media offers insights about the lived religious experiences of American and British Muslims.

Narrative authority

What unites these series is their rejection of reductive and stereotypical narratives. Muslim characters in these shows are not defined by violence, trauma or assimilation. Nor do they serve as spokespeople for all Muslims; they are written as flawed and evolving individuals.

This wave of nuanced portrayals of Muslim life includes other recent productions such as Netflix’s 2022 series “Mo” and Hulu’s 2025 reality series “Muslim Matchmaker,” which centers real people whose lives and romantic journeys showcase American Muslim life in authentic ways. Muslims in the show are depicted as having various professions, levels of faith and life experiences.

These series and their creators signal that real progress comes when Muslim voices are telling their own stories, not simply reacting to the gaze of outsiders or the pressures of political headlines. By foregrounding daily ritual, spiritual aspiration and even awkwardness and desire, “Ramy,” “Man Like Mobeen” and “We Are Lady Parts” all refuse the burden of “representation.”

By moving away from the binary of “threatening other” versus “assimilated citizen,” this new wave of media challenges the legacy of Orientalism. Instead, they offer characters who reflect the complex realities of Muslim lives that are messy, joyful and evolving.

Tazeen M. Ali does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Iran-US nuclear talks may fail due to both nations’ red lines – but that doesn’t make them futile

The US administration may sense that Iran is weak and ready to do a deal. But negotiations could be…

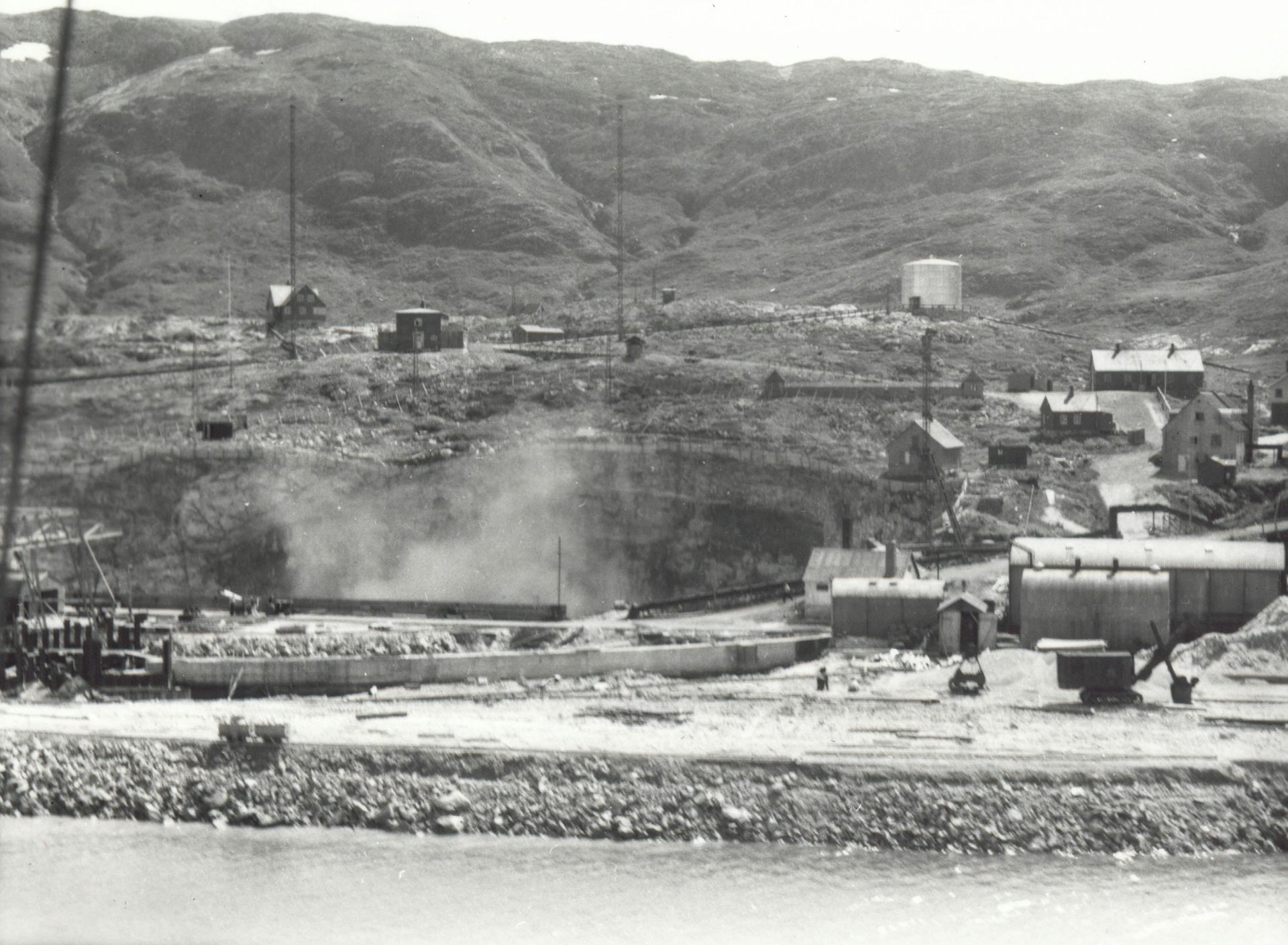

In World War II’s dog-eat-dog struggle for resources, a Greenland mine launched a new world order

Strategic resources have been central to the American-led global system for decades, as a historian…

Revisiting the story of Clementine Barnabet, a Black woman blamed for serial murders in the Jim Crow

In 1912, a young Black woman’s supposed religious beliefs were quickly blamed to make sense of a terrifying…