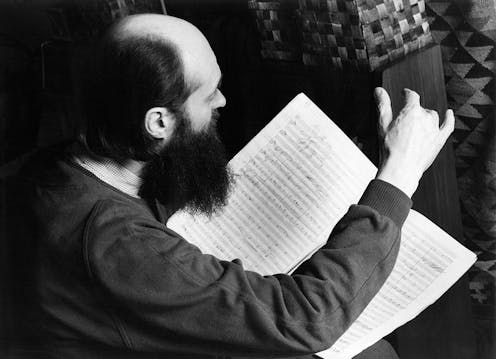

Sacred texts and ‘little bells’: The building blocks of Arvo Pärt’s musical masterpieces

The Estonian composer has written some of the world’s most performed contemporary classical music. Many fans may not realize how deep the religious influences on his work are.

The Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, who turns 90 on Sept. 11, 2025, is one of the most frequently performed contemporary classical composers in the world. Beyond the concert stage and cathedral choir, Pärt’s music features heavily in film and television soundtracks: “There Will Be Blood,” “Thin Red Line” or “Wit,” for instance. It is often used to evoke profound emotions and transcendent spirituality.

Many Estonians grew up hearing the music Pärt wrote for children’s films and Estonian cinema classics in the 1960s and ‘70s. Popes and Orthodox patriarchs honor him, and Pärt’s music has received the highest levels of recognition, including Grammy Awards. In 2025, Pärt is being celebrated in Estonia, at Carnegie Hall and around the world.

Behind much of Pärt’s popularity – and his listeners’ devotion – is his engagement with sacred Christian texts and Orthodox Christian spirituality. Yet his music has inspired a broad range of artists and thinkers: Icelandic singer Björk, who admires its beauty and discipline; the theater artist Robert Wilson, who was drawn to its quality of time; and Christian theologians, who appreciate its “bright sadness.”

As a music scholar with expertise in Estonian music and Orthodox Christianity, and a longtime Pärt fan, I am fascinated by how Pärt’s exploration of Christian traditions – at once subtle and fervent – appeals to so many. How does this happen musically?

Tintinnabuli

Pärt emerged from a period of personal artistic crisis in 1976. In a now-legendary concert, he introduced the world to new music composed using a technique he invented called “tintinnabuli,” an onomatopoeic Latin word meaning “little bells.”

Tintinnabuli is music reduced to its elemental components: simple melodic lines derived from sacred Christian texts or mathematical designs and married to basic harmonies. As Pärt describes it, tintinnabuli is the benefit of reduction rather than complexity – freeing the elemental beauty of his music and the message of his texts.

This was a departure from Pärt’s earlier modernist and experimental music, and expressed a yearslong struggle to reconcile his newfound commitment to Orthodox Christianity and his rigorous artistic ideals. Pärt’s journey is documented in the dozens of notebooks he kept, beginning in the 1970s: religious texts, diary entries, drawings and ideas for musical compositions – a documentary trove of Christian musical creativity.

Tintinnabuli was inspired, in part, by Pärt’s interest in much earlier styles of Christian music, including Gregorian chant – the single-voice singing of Roman Catholicism – and Renaissance polyphony, which weaves together multiple melodic lines. Because of its associations with the church, this music was ideologically fraught in an anti-religious Soviet Estonia.

In Pärt’s notebooks from the 1970s, there are pages and pages of musical sketches where he works out early music-inspired approaches to texts and prayers – the seeds of tintinnabuli. The technique became his answer to existential creative questions: How can music reconcile human subjectivity and divine truths? How can a composer get out of the way, so to speak, to let the sounds of sacred texts resonate? How can artists and audiences approach music so that, to use Pärt’s famous expression, “every blade of grass has the status of a flower”?

In a 2003 conversation with the Italian musicologist Enzo Restagno, Pärt’s wife, Nora, offered an equation to understand how tintinnabuli works: 1+1 = 1.

The first element – the first “1” – is melody, as singer and conductor Paul Hillier lays out in his 1997 book on Pärt. Melody expresses a subjective experience of moving through the world. It centers around a given musical note: the “A” key on the piano, for instance.

The second element – the “+1” – is tintinnabuli itself: the presence of three pitches, sounding together as a bell-like halo: A, C, E.

Finally, the third element – the “= 1” – is the unity of melodic and tintinnabuli voices in a single sound, oriented around a central musical note.

Formulas

Here’s the crux of Arvo Pärt’s work: the relationship of 1+1, melody and harmony, is ordered not by moment-to-moment choices, but by formulas meant to magnify the sound and structure of sacred texts.

A simple tintinnabuli formula might go like this: If the melody rises four notes with four syllables of text, the notes of the tintinnabuli triad will follow beneath that line without overlapping. It supports and steers. Or if the melody falls five notes with five syllables of text, the notes of the tintinnabuli triad will alternate above and below that line to create a different musical texture – all organized around symmetry.

Pärt often lets the number of syllables in a word, the length of a phrase or verse, and the sound of a language shape his formulas. That is why Pärt’s music in English, with its many single-syllable words, consonant clusters and diphthongs, sounds one way. And that is why his music in Church Slavonic, the liturgical language for many Orthodox Christians, sounds another way.

Tintinnabuli is about simplicity and beauty. The genius of Pärt’s work is how his formulas feel like the musical expression of timeless truths. In a 1978 interview with the journalist Ivalo Randalu, Nora Pärt recalled what her husband once said about tintinnabuli’s formulas: “I know a great secret, but I know it only through music, and I can only express it through music.”

Silence

If this all seems coldly formulaic, it isn’t. There is a sensuousness to Arvo Pärt’s tintinnabuli music that connects with listeners’ bodily experience. Pärt’s formulas, born out of long, prayerful periods with sacred texts, offer beauty in the warmth and friction of relationships: melody and tintinnabuli, word and the limits of language, sounds and silence.

“For me, ‘silent’ means the ‘nothing’ from which God created the world,” Pärt told the Estonian musicologist Leo Normet in 1988. “Ideally, a silent pause is something sacred.”

Silence is a common trope in Pärt’s music – indeed, the second movement of his tintinnabuli masterpiece “Tabula rasa,” the title work on the 1984 ECM Records release that brought him to global attention, is “Silentium.”

Any sounding music is not silent, of course – and, in human terms, silence is largely metaphorical, since we cannot escape sound into the silence of absolute zero or a vacuum.

But Pärt’s silence is different. It is spiritual stillness communicated through his musical formulas but made sensible through the action of human performers. It is a composer’s silence as he gets out of the way of a sacred text’s musicality to communicate its truth. Without paradox, Pärt’s popularity today may well arise from the silence of his music.

Jeffers Engelhardt does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?

How transparent policies can protect Florida school libraries amid efforts to ban books

Well-designed school library policies make space for community feedback while preserving intellectual…

Colleges face a choice: Try to shape AI’s impact on learning, or be redefined by it

Colleges and universities are taking on different approaches to how their students are using AI –…