3 states push to put the Ten Commandments back in school – banking on new guidance at the Supreme Co

Louisiana, Texas and Arkansas are testing a Supreme Court precedent barring displays of the Ten Commandments’ display in public school classrooms.

As disputes rage on over religion’s place in public schools, the Ten Commandments have become a focal point. At least a dozen states have considered proposals that would require classrooms to post the biblical laws, and three passed laws mandating their display in 2024-2025: Louisiana, Arkansas and Texas.

All three laws have been at least partially blocked – most recently Texas’ law – after federal trial court rulings. But the ongoing cases seem aimed at overturning a 45-year-old U.S. Supreme Court precedent prohibiting the posting of the Ten Commandments in public schools.

As religion and education law researchers, we believe this situation is especially noteworthy because of its timing. The Supreme Court has been using a new standard to assess religious freedom cases – and its judgments on religion’s role in public education are perhaps the most religion-friendly they have ever been.

The Ten Commandments and the courts

Litigation over the Ten Commandments is not new. More than a dozen early cases generally upheld laws and policies mandating their recitation in schools. These enactments survived because the Supreme Court did not extend the First Amendment to the states until 1940.

However, the issue of posting the commandments in schools first surfaced in 1980. In a case called Stone v. Graham, the Supreme Court struck down a Kentucky statute requiring displays of the Ten Commandments in classrooms. The court reasoned that the law violated the First Amendment’s establishment clause: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

At the time, the court used three criteria, known as the “Lemon test,” to evaluate whether a government action violated the establishment clause. According to this test – which developed from a 1971 Supreme Court decision – governmental actions must have a secular legislative purpose, and their main effect may neither advance nor inhibit religion. In addition, they must avoid excessive entanglement with religion.

When Kentucky’s case came before the court, justices rejected its argument that the displays served a secular educational purpose. The majority did not think that a small notation on posters describing the Ten Commandments as the “fundamental legal code of Western Civilization and the Common Law of the United States” was sufficient, and wrote that the posters were “plainly religious in nature.”

Twenty-five years later, in 2005, disputes over public displays of the Ten Commandments reached the Supreme Court once more. This time, the displays were not in schools. But the first controversy arose, again, in Kentucky.

Officials in two counties had erected displays at courthouses that included the Ten Commandments, Magna Carta and the Declaration of Independence. The justices limited their order to one dispute, in McCreary County, invalidating the display for violating the establishment clause – largely because it lacked a secular legislative purpose.

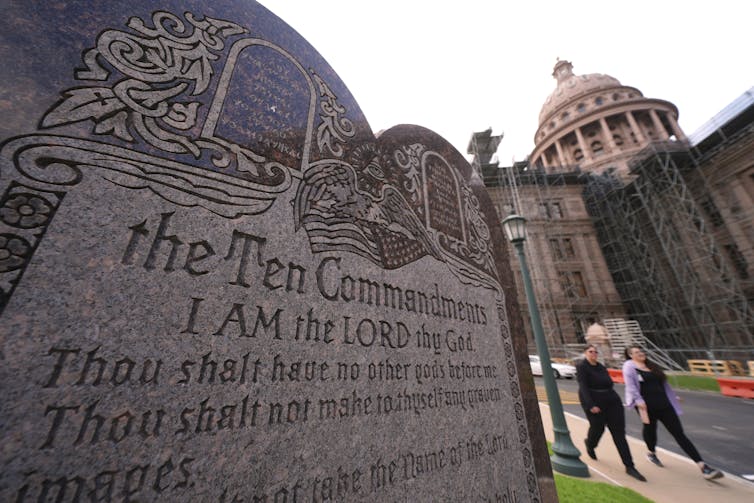

On the same day, though, the Supreme Court reached the opposite result in another case, Van Orden v. Perry. The court permitted a display including the Ten Commandments to remain on the grounds of the Texas Capitol in Austin, where it was one of 17 monuments and 21 historical markers.

Unlike the fairly new displays in Kentucky, the long-standing one in Texas, with the first monument erected in 1891, was built using private funds. The court left the Ten Commandments monument in place because it was a more passive display. The Capitol grounds are spread out over 22 acres, meaning the display was not as readily apparent as if it had been posted in classrooms for children to see every day.

‘Follow God’s law’

In 2024, a federal trial court in Louisiana blocked a state law mandating that the Ten Commandments be posted in public schools. Undeterred, Arkansas and Texas passed similar legislation the following year.

Arkansas Act 573, signed into law in April 2025, obligated officials to display a “durable poster or framed copy” of the Ten Commandments in all state and local government buildings, including public school and college classrooms.

Republican Rep. Alyssa Brown, one of the Arkansas bill’s sponsors, described it as an effort to educate students on how the United States was founded and how the founders framed the Constitution.

“We’re not telling every student they have to believe in this God,” she told a legislative committee, “but we are upholding what those historical documents mean and that historical national motto.”

Texas, meanwhile, adopted a similar law in June 2025.

“It is incumbent on all of us to follow God’s law, and I think we would all be better off if we did,” the bill’s sponsor in the Texas House, Republican Rep. Candy Noble, said during debate.

Shift at SCOTUS

Supporters of these laws have claimed that they are constitutional because of an important shift at the Supreme Court. In 2022, the court adopted a new “history and tradition test” to assess religion in public places, including classrooms.

The “history and tradition test” originated in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, a case about a public high school football coach who prayed on the field at the end of games. The Supreme Court ruled in 2022 that school officials could not prevent him from doing so, because it was personal religious observance protected by the First Amendment’s other religion clause: that the government shall not prohibit the “free exercise” of religion.

Kennedy charted a new course on religion’s place in public life. Acknowledging that it “long ago abandoned Lemon and its endorsement test offshoot,” the justices explained that “the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by ‘reference to historical practices and understandings.‘” It remains to be seen how this vague standard plays out in later cases.

Blocked – for now

Opponents quickly challenged Arkansas’ law. Seven families from various religious traditions filed suit, arguing that it was a direct violation of both the establishment and free exercise clauses of the First Amendment.

On Aug. 4, a federal trial court judge ruled in the families’ favor. The court found that the required display would have “forced [students] to engage with” the Ten Commandments, and “perhaps to venerate and obey” them. The trial court also applied the new historical practices and understandings test, holding that there was no evidence of a tradition to display the Ten Commandments in public schools permanently.

The court thus temporarily barred school boards from enforcing Act 573, pending any further appeals.

Two weeks later, a federal trial court in Texas temporarily blocked the law on the ground that it likely violated the First Amendment, though the judge’s order only applies to 11 districts.

Religion’s role

Controversy over the Ten Commandments continues to raise larger questions over the role of religion in public education.

Supporters of such bills seemingly fail to recognize that they cannot impose their religious values in the public sphere. At the same time, some opponents – including Jewish, Christian, Unitarian Universalist, Hindu and nonreligious plaintiffs – do not necessarily wish to remove religion entirely from educational institutions.

These critics want to uphold the principle, as the Supreme Court announced, that the government must demonstrate “neutrality between religion and religion, and between religion and nonreligion.” In other words, critics do not want one religion or religion generally to dominate.

Today’s challenge is to find the balance in public life. We believe the courts and legislatures must avoid sending the message that religion has no place in a free and open society – just as they must not permit one set of values to dominate, as the bills in Arkansas and Texas seem to aspire to do.

How the courts and legislatures balance the rights of the majority and minority in these disputes over the place of the Ten Commandments in public life may go a long way toward shaping the future of religious freedom in American public education.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Violent aftermath of Mexico’s ‘El Mencho’ killing follows pattern of other high-profile cartel hits

Members of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel have set up roadblocks and attacked property and security…

Crowdfunded generosity isn’t taxable – but IRS regulations haven’t kept up with the growth of mutual

Some Americans are discovering that monetary help they received from friends, neighbors or even strangers…

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?