Civil servant exodus: How employees wrestle with whether to stay, speak up or go

Federal workers face unique challenges. But part of their dilemma is familiar to many Americans who have to wrestle with dramatic changes in the workplace.

For many Americans, work is not just about earning a paycheck. It is a centerpiece of their lives, and they want their job to be meaningful.

Decades of research suggest this is true for most federal civil servants, who aim to serve not only their organizations and their missions, but also the public and the nation. Over the course of President Donald Trump’s first administration, from 2017-21, we spoke with dozens of federal civil servants. They described their jobs as a calling aligned with their ideals – to serve the government, uphold democracy and serve the public.

Turbulent change during Trump’s first term, however, tested many workers. Over a quarter of the civil servants we spoke with ultimately left the federal government.

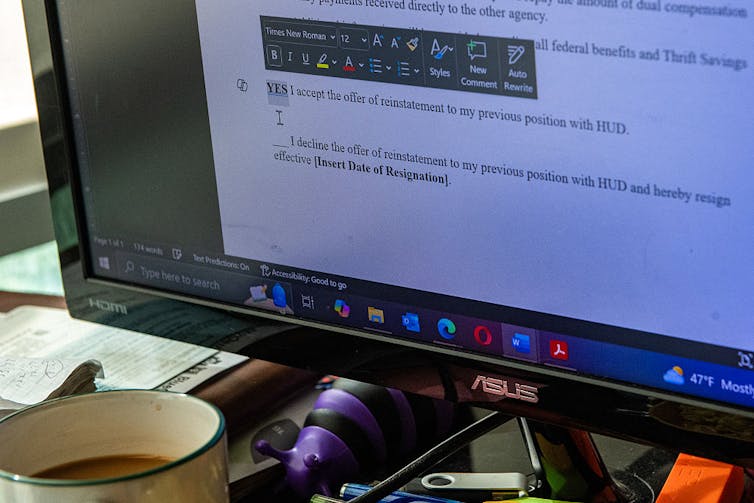

Since the start of his second term, Trump has attempted a far more sweeping overhaul of the federal bureaucracy. More than 50,000 federal workers have been fired or targeted for layoffs. The U.S. Agency for International Development was shuttered, for example, and more than 80% of employees have been fired from AmeriCorps and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Another 154,000 federal workers accepted the government’s buyout offers, which are structured as “deferred resignations.”

Yet there are similarities with Trump’s first term, such as his and his appointees’ attacks on civil servants’ loyalty and the administration’s efforts to punish dissent.

Our interviews from Trump’s first term – the basis for the 2025 book “The Loyalty Trap” – may give insight into what civil servants are experiencing today. In some ways, their concerns are unique to government work. Yet they also face a challenge many workers confront during dramatic changes at their organization, regardless of their field: whether to stay or go.

Nonpartisan workforce

The federal civil service is composed primarily of career professionals who work for a mission-driven agency, not just a specific administration. These employees consider themselves nonpartisan, prepared to serve presidents from either party.

When a new administration takes over, whether Democratic or Republican, it installs political appointees to lead the agencies that execute federal law. These agencies help develop federal regulations, enforce laws and regulations, provide services and carry out policies. Career civil servants expect to carry out appointees’ instructions, and are under legal and ethical obligations to do so.

The ethical code and oath of office civil that servants swear to upon starting their positions require them to uphold the Constitution, laws and ethical principles, and to “faithfully discharge the duties of [their] office.” They may not “use public office for private gain” and are required to report any “waste, fraud, abuse, and corruption.”

Federal employees expect significant changes in policy direction and describe it as part of the job. As one State Department worker told us in 2018:

“The president is elected by the people and can define his or her own foreign policy, and our job as career officers of the State Department is to enact that person’s policy. So I have no problem — I have my own moral questions about what the president’s foreign policy choices are – but from a commitment and service oath that I’ve taken to work at the State Department, it is my job to implement the intent of the president and the Secretary of State.”

Loyalty trap

Under the first Trump administration, however, many interviewees described a new level of abrupt change and politicization, where personal loyalty to the president seemed prioritized over their agencies’ missions and norms.

Civil servants must abide by the Hatch Act, which forbids some kinds of political activities, like hosting fundraisers – rules meant to shield them from political pressure and keep promotions merit-based. During the first term, however, Trump officials repeatedly violated the Hatch Act, according to a 2021 federal probe.

In this environment during the first Trump administration, “Loyalty [was] to not question,” said a senior officer at the Environmental Protection Agency. Amid increasing mistrust and suspicion, she believed that “whenever you raised a question in this environment, you were thought to be leaking as well.” This cut against some civil servants’ understanding that it was their job, as longtime agency workers and experts, to provide the best advice possible.

Emphasis on personal loyalty was difficult for some of them to reconcile with loyalty to the missions of their agencies or to the public interest, particularly as many policies took a sharp turn. By January 2021, around three-quarters of the regulations, guidance documents and agency memos the Trump administration issued that were challenged in court had been invalidated or withdrawn, according to research at New York University.

Some civil servants working to bolster democracy around the world and at home, for example, were disturbed by shifts in foreign policy. The president frequently praised authoritarian leaders with poor human rights records – such as Vladimir Putin of Russia, Kim Jung Un of North Korea and Reçep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey – while giving the cold shoulder to allies in Europe.

“The thrust of U.S. foreign policy has generally followed a pretty predictable path,” observed one longtime member of the State Department, who had worked under both Republican and Democratic administrations. “This administration has come in and has basically disregarded the overall imperative that we have to promote democracy and to promote transparency.”

Around 80% of our interviewees said they were experiencing moral dissonance as a result of the sense that their own values, job standards and political leaders’ expectations did not align. These workers were experiencing what we call a “loyalty trap”: the sense of being caught between following higher-ups’ directives and complying with other professional and ethical obligations.

Eyeing the exits

German economist Albert Hirschman’s 1970 book, “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty,” helps explain what workers do when they believe their organization is in decline. Hirschman argued that loyalty to an organization can delay a worker’s decision to leave and motivate them to speak up and push for improvement.

Other studies since then have also examined how loyalty shapes workers’ decisions. Research on industries from journalism to mining and taxi operations suggests that when employees feel they have no opportunity to voice dissent and influence the group’s direction, even the most loyal workers may eventually decide to exit.

However, loyalty to the mission of an organization can shape a worker’s decision in complex ways. Sociologist Elizabeth A. Hoffman, for example, studied workers in conventional versus cooperative, employee-owned businesses. She found that employees in a cooperative food distribution company – who expressed strong allegiance to the company and their co-workers – were more likely to mention exiting in response to grievances than their counterparts in a conventional company. She concluded that the cooperative’s workers’ greater “zeal” for the group’s mission actually made them more likely to consider leaving when they felt frustrated or betrayed.

These findings echo themes among civil servants we spoke with who wound up leaving the government – people who valued public service but doubted their power to use their voice to do work as they saw fit.

Civil servants’ exits can be costly for them and their families – but also for their governments, as public administration scholars have found in countries around the world. Experienced workers’ departure can result in the loss of institutional knowledge, and they are often replaced with political loyalists. A 2023 review of almost 100 studies – including research from more than 150 countries – concluded that governments where employees were hired based on their education and work experience, not their politics, had less corruption, more efficiency and greater public trust.

Under the current U.S. administration – which is openly punishing dissent among civil servants – we expect an even greater number of employees to contemplate departure.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Colleges face a choice: Try to shape AI’s impact on learning, or be redefined by it

Colleges and universities are taking on different approaches to how their students are using AI –…

Meekness isn’t weakness – once considered positive, it’s one of the ‘undersung virtues’ that deserve

The word ‘meekness’ might seem old-fashioned – and not a positive trait. But understanding its…

How Homeland Security’s subpoenas and databases of protesters threaten the ‘uninhibited, robust, and

It’s difficult to measure what is lost when an opinion is never voiced and impossible to catalogue…