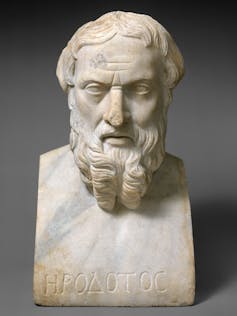

Authoritarian rulers aren’t new – here’s what Herodotus, an early Greek historian, wrote about them

Herodotus showed how human beliefs and choices affected the fate of nations. His insights are still relevant.

“No Kings” rallies. “Good Trouble” protests. “Rage against the Regime” uprisings. These events in the first seven months of President Donald Trump’s second term, along with public opinion polls, show that many Americans are concerned about Trump’s expansive use of executive power.

Views on this issue often have a partisan slant. Republicans express more concern about presidential power when Democrats control the White House, and vice versa.

But many in both parties prefer that U.S. political leaders work through established channels, rather than through unconventional actions that may pose challenges to the Constitution and the rule of law, such as mass firings and large-scale deportations.

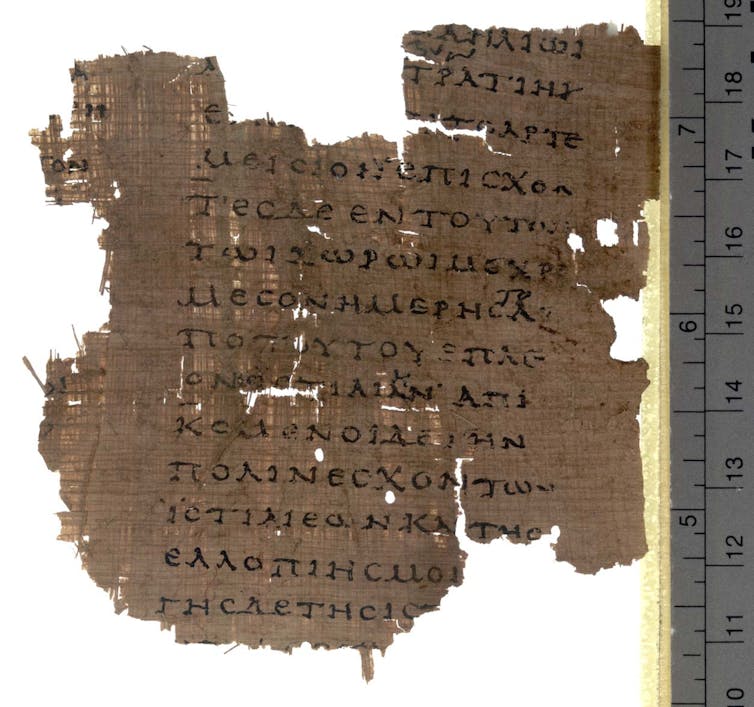

As a professor of classics, I know that concerns about authoritarianism go back thousands of years. One early discussion appears in the work of the fifth-century B.C.E. Greek writer Herodotus, whose “History” – sometimes called “Histories” – is considered the first great prose narrative in Western literature.

In it, Herodotus analyzed the Persian invasion of Greece – the defining event of his time. To understand how Greece, a much smaller power, achieved a major victory over Persia, Herodotus explored the nature of effective leadership, which he saw as a critical factor in the conflict’s outcome.

A shocking upset

Persia was already a vast empire when it invaded Greece, a tiny country made up of independent city-states. The Persians expected a quick and easy victory.

Instead, the Greco-Persian Wars lasted over a decade, from 490 to 479 B.C.E. They ended with Greece defeating the Persians – a shocking upset. Consequently, Persia abandoned its westward expansion, while various Greek city-states formed a tenuous alliance that lasted nearly 50 years.

To explain this unexpected outcome, Herodotus described how Persian and Greek societies developed before this crucial conflict. In his view, the fact that many Greek city-states had representative governments enabled the Greek victory.

These systems allowed individuals to participate in discussing strategies and resulted in the Greeks uniting to fight for freedom. For example, when the Persian fleet was headed toward mainland Greece, the Athenian general Miltiades says, “Never before have we been in such extreme danger. If we give in to the Persians, we will suffer greatly under the tyrant Hippias.”

Herodotus tended to put his political philosophies into the mouths of historical figures such as Miltiades. He condensed his thoughts about government into what historians call the “Constitutional Debate,” a fictional conversation among three real characters: Persian noblemen named Otanes, Megabazus and Darius.

Persia’s ascent

For centuries prior to invading Greece, Persia had been a small region inhabited by various ancient Iranian peoples and controlled by the neighboring kingdom of Media. Then, in 550 B.C.E., King Cyrus II of Persia overthrew the Medes and expanded Persian territory into what became the Achaemenid Empire.

Thanks to his effective leadership and tolerance for the customs of cultures he conquered, historians call him “Cyrus the Great.”

His son and successor, Cambyses, was less successful. He added Egypt to the Persian empire, but according to Herodotus, Cambyses acted erratically and cruelly. He desecrated the pharaoh’s tomb, mocked the Egyptians’ gods, and killed their sacred Apis bull. He also demanded that Persian judges change the laws so that he could marry his own sisters.

After Cambyses died childless, various factions vied for the Persian throne. Herodotus set his discussion about alternative political systems in this unstable period.

The case for democracy

Otanes, the first speaker in the Constitutional Debate, says “the time has passed for any one man among us to have absolute power.” He recommends that the Persian people themselves handle state affairs.

“How can monarchy continue to be our norm, when a monarch can do whatever he wants, with no accountability whatsoever?” Otanes asks. Even worse, a monarch “disrupts the laws,” as Cambyses did.

Otanes favors rule by the many, which he calls “isonomia,” meaning “equality under the law.” In this system, he explains, politicians are elected and held responsible for their behavior and make decisions transparently.

Today, unlike Otanes, Republican members of Congress appear reluctant to hold Trump responsible for anything or ensure transparency within the administration. Prominent Democrats, including U.S. Rep. Jamie Raskin and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, are challenging Trump administration actions that they view as lawless, such as freezing of funds authorized by Congress.

Do oligarchs know better?

Otanes’ fellow nobleman, Megabazus, agrees that the Persians should abolish monarchy, but he raises concerns about rule by the people.

“The masses are useless – there’s nothing more witless and violent than a crowd,” Megabazus asserts. He believes “commoners” don’t understand the intricacies of policymaking.

Instead, Megabazus suggests oligarchy, or “rule by a few.” Choose the best men in Persia and let them rule everyone else, he urges, because they “will naturally come up with the best ideas.”

But Megabazus doesn’t explain who would qualify as “the best men” or who would select them.

The U.S. has occasionally resembled an oligarchy, with small, elite groups holding most political power. For example, Article 1, Section 3 of the original Constitution provided for election of senators by state legislators, not directly by the people. Senators were not elected by popular vote until the 17th Amendment passed in 1913.

More recently, Trump has received millions of dollars in support from billionaire tech industry leaders such as Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos, who hope to influence antitrust policy and deregulation. The Department of Government Efficiency, headed by Musk before he stepped down in May 2025, is now run by young men with virtually no government experience. DOGE’s cuts to programs such as humanitarian aid are wreaking havoc across the globe.

What about monarchy?

The third speaker, Darius, sees democracy and oligarchy as equally flawed. He points out that even well-intentioned oligarchs fight among themselves because “each wants his own opinion to prevail.” This leads to hatred and worse, much like the Trump-Musk relationship gone sour.

Rather, Darius asserts, “using good judgment, a monarch will be a flawless guardian of the people.” He argues that since Persia was freed by one man, King Cyrus II, Persians should maintain their traditional monarchy.

Darius doesn’t explain how to ensure a monarch’s good judgment. But his argument wins out. It had to, since in reality Darius became Persia’s next king. Kings, or shahs, ruled Persia – it became known as Iran in 1935 – until the Iranian Revolution of 1979 eliminated the monarchy and established the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Trump is not technically a monarch, but some believe he acts like one. He and his administration have ignored court orders, preempted the powers of Congress and sought to silence his critics by attacking protected free speech.

Lessons from Herodotus

Herodotus himself was largely pro-democracy, but his Constitutional Debate doesn’t endorse one form of government. Instead, it highlights principles of good leadership. These include accountability, moderation and respect for “nomos,” a Greek term encompassing the concepts of custom and law.

Herodotus emphasizes: “Formerly great cities have become small, while small cities have become great.” Human fortune changes constantly, and Persia’s failure to conquer Greece is just one example.

History has seen the rise and fall of many world powers. Is the United States next? Herodotus viewed the Persian monarchy, whose kings believed their own authority was paramount, as the weakness that led to their astounding defeat in 479 B.C.E.

Debbie Felton is affiliated with the Democratic Party (registered to vote).

Read These Next

Picky eating starts in the womb – a nutritional neuroscientist explains how to expand your child’s p

While genes do influence some food preferences, positive experiences can help make new tastes easier…

Algorithms that customize marketing to your phone could also influence your views on warfare

AI systems are getting good at optimizing persuasion in commerce. They are also quietly becoming tools…

Colleges face a choice: Try to shape AI’s impact on learning, or be redefined by it

Colleges and universities are taking on different approaches to how their students are using AI –…