From printing presses to Facebook feeds: What yesterday’s witch hunts have in common with today’s mi

Who bears responsibility when false information leads to real harm?

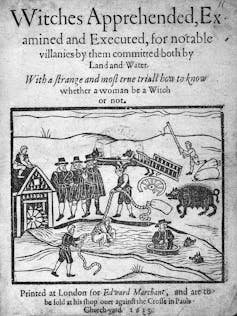

Between 1400 and 1780, an estimated 100,000 people, mostly women, were prosecuted for witchcraft in Europe. About half that number were executed – killings motivated by a constellation of beliefs about women, truth, evil and magic.

But the witch hunts could not have had the reach they did without the media machinery that made them possible: an industry of printed manuals that taught readers how to find and exterminate witches.

I regularly teach a class on philosophy and witchcraft, where we discuss the religious, social, economic and philosophical contexts of early modern witch hunts in Europe and colonial America. I also teach and research the ethics of digital technologies.

These fields aren’t as different as they seem. The parallels between the spread of false information in the witch-hunting era and in today’s online information ecosystem are striking – and instructive.

Birth of a publishing empire

The printing press, invented around 1440, revolutionized how information spread – helping to create the era’s equivalent of a viral conspiracy theory.

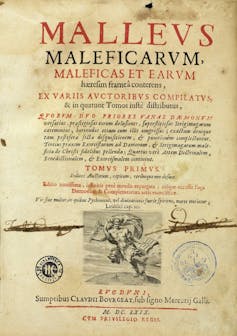

By 1486, two Dominican friars had published the “Malleus Maleficarum,” or “Hammer of Witches.” The book has three central claims that came to dominate the witch hunts.

First, it describes women as morally weak and therefore more likely to be witches. Second, it tightly links witchcraft with sexuality. The authors claim that women are sexually insatiable – part of what leads them to witchcraft. Third, witchcraft involves a pact with the devil, who tempts would-be witches through pleasures such as orgies and sexual favors. After establishing these “facts,” the authors conclude with instructions for interrogating, torturing and punishing witches.

The book was a hit. It had more than two dozen editions and was translated into multiple languages. While “Malleus Maleficarum” was not the only text of its kind, its influence was enormous.

Prior to 1500, witch hunts in Europe were rare. But after the “Malleus Maleficarum,” they picked up steam. Indeed, new printings of the book correlate with surges in witch-hunting in Central Europe. The book’s success wasn’t just about content; it was about credibility. Pope Innocent VIII had recently affirmed the existence of witches and conferred authority on inquisitors to persecute them, giving the book further authority.

Ideas about witches [from earlier texts and folklore] – such as the fact that witches could use spells to make penises vanish – were recycled and repackaged in the “Malleus Maleficarum,” which in turn served as a “source” for future works. It was often quoted in later manuals and woven into civic law.

The popularity and influence of the book helped crystallize a new domain of expertise: demonologist, an expert on the nefarious activities of witches. As demonologists repeated one another’s spurious claims, an echo chamber of “evidence” was born. The identity of the witch was thus formalized: dangerous and decisively female.

Skeptics fight back

Not everyone bought into the witch hysteria. As early as 1563, dissenting voices emerged – though, notably, most didn’t argue that witches weren’t real. Instead, they questioned the methods used to identify and prosecute them.

Dutch physician Johann Weyer argued that women accused of witchcraft were suffering from melancholia – what we might now call mental illness – and needed medical treatment, not execution. In 1580, French philosopher Michel de Montaigne visited imprisoned witches and concluded they needed “hellebore rather than hemlock”: medicine rather than poison.

These skeptics also identified something more insidious: the moral responsibility of people spreading the stories. In 1677, English chaplain, physician and philosopher John Webster wrote a scathing critique, claiming that most demonologists’ texts were straightforward copy and paste jobs where the authors repeated one another’s lies. The demonologists offered no original analysis, no evidence and no witnesses – failing to meet the standards of good scholarship.

The cost of this failure was enormous. As Montaigne wrote, “The witches of my neighborhood are in mortal danger every time some new author comes along and attests to the reality of their visions.”

Demonologists benefited from the social and political status associated with the popularity of their books. The financial benefit was, for the most part, enjoyed by the printers and booksellers – what today we refer to as publishers.

Witch hunts petered out throughout the 1700s across Europe. Doubt about the standards of evidence, and increased awareness that accused “witches” may have been suffering from delusion, were factors in the end of the persecution. The skeptics’ voices were heard.

Psychology of viral lies

Early modern skeptics understood something we’re still grappling with today: Certain people are more vulnerable to believing extraordinary claims. They identified “melancholics,” people predisposed to anxiety and fantastical thinking, as particularly susceptible.

Nicolas Malebranche, a 17th-century French philosopher, believed that our imaginations have enormous power to convince us of things that are not true – especially fear of invisible, malevolent forces. He noted that “extravagant tales of witchcraft are taken as authentic histories,” increasing people’s credulity. The more stories, and the more they were told, the greater the influence on the imagination. The repetition served as false confirmation.

“If they were to cease punishing (women accused of witchcraft) and treat them as mad people,” Malebranche wrote, “in a little while they would no longer be sorcerers.”

Today’s researchers have identified similar patterns in how misinformation and disinformation – false information intended to confuse or manipulate people – spreads online. We’re more likely to believe stories that feel familiar, stories that connect to content we’ve previously seen. Likes, shares and retweets becomes proxies for truth. Emotional content designed to shock or outrage spreads far and fast.

Social media channels are particularly fertile ground. Companies’ algorithms are designed to maximize engagement, so a post that receives likes, shares and comments will be shown to more people. The more viewers, the higher the likelihood of more engagement, and so on – creating a cycle of confirmation bias.

Speed of a keystroke

Early modern skeptics reserved their harshest criticism not for those who believed in witches but for those who spread the stories. Yet they were curiously silent on the ultimate arbiters and financial beneficiaries of what got printed and circulated: the publishers.

Today, 54% of American adults get at least some news from social media platforms. These platforms, like the printing presses of old, don’t just distribute information. They shape what we believe through algorithms that prioritize engagement over accuracy: The more a story is repeated, the more priority it gets.

The witch hunts offer a sobering reminder that delusion and misinformation are recurring features of human society, especially during times of technological change and social upheaval. As we navigate our own information revolution, those early skeptics’ questions remain urgent: Who bears responsibility when false information leads to real harm? How do we protect the most vulnerable from exploitation by those who profit from confusion and fear?

In an age when anyone can be a publisher, and extravagant tales spread at the speed of a keystroke, understanding how previous societies dealt with similar challenges isn’t just academic – it’s essential.

Julie Walsh receives funding from the National Science Foundation

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Detroit was once home to 18 Black-led hospitals – here’s how to understand their rise and fall

In the early 20th century, Detroit’s Black medical professionals created a network of health care…

From moral authority to risk management: How university presidents stopped speaking their minds

Nearly 150 universities and colleges have adopted institutional neutrality pledges since 2023.