How the Catholic Church helped change the conversation about capital punishment in the United States

Catholic opposition to the death penalty is relatively new in the church’s history, but has helped shape public debate.

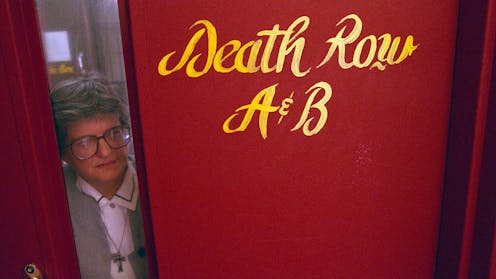

Thirty years ago, the film “Dead Man Walking” had its debut in movie theaters around the United States. It was a box office hit, and critics lavished it with praise. Lead actress Susan Sarandon won an Academy Award for her portrayal of Sister Helen Prejean, the spiritual adviser to a death row inmate played by Sean Penn.

But the film’s impact went far beyond the artistic realm. It exposed a mass audience to a perspective on the death penalty informed by the Catholic faith of a devout, if somewhat unconventional, nun.

The actual Sister Helen had published her memoir, “Dead Man Walking,” two years before, raising her profile as an activist against the death penalty. Recalling her experience outside the execution chamber of Elmo Patrick Sonnier, one of the people she counseled, Prejean later wrote, “I touched him in the only way I could. I told him: ‘Look at my face. I will be the face of Christ, the face of love for you.’”

She made it her mission to show that “everybody’s worth more than the worst thing they’ve ever done in their life.” As she once told an interviewer, “Jesus said, ‘Love your enemy.’ Jesus didn’t say, ‘Execute the hell out of the enemy.’”

That belief was featured prominently in the film and offered a counterpoint to the popular tough-on-crime rhetoric of the 1990s. Back then, 80% of the American public supported capital punishment.

Today, that is no longer true. Support for the death penalty has declined to around 50%.

As a death penalty scholar, I have studied those changes. The church’s anti-death penalty teaching has helped provide both a moral foundation and political respectability for those working to end the death penalty.

Church teachings

But that teaching is relatively new in the church, dating back to the past half-century. For most of its history, the Catholic Church did not oppose the death penalty.

During the Middle Ages, the church endorsed the execution of heretics and held firm that secular authorities could and should put people to death for serious crimes. And in the early 20th century, Vatican City’s penal code permitted the death penalty for anyone who attempted to kill a pope. Pope Paul VI changed that in 1969.

When John Paul II became pope a decade later, he pushed the church further away from its historic embrace of the death penalty, calling it “cruel and unnecessary.” And in 2018, under Pope Francis, the Vatican revised the section on capital punishment in the Catechism, the summary of Catholic doctrine.

The death penalty “is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person,” and deprives “the guilty of the possibility of redemption,” the new version says. This teaching committed the church to work for its abolition.

In his 2020 encyclical Fratelli Tutti, Francis stated that the death penalty is “inadequate from a moral standpoint and no longer necessary from that of penal justice.” In 2024, he again called for “the abolition of the death penalty, a provision at odds with Christian faith and one that eliminates all hope of forgiveness and rehabilitation.”

Impact in the US

The changed situation of capital punishment in this country is largely attributable to a change in the strategy and tactics of the abolitionist movement. Instead of talking about the death penalty in abstract terms, activists began to focus on the day-to-day realities of its administration.

Today, advocates in what I have called the “new abolitionism” focus on the prospect of executing the innocent, racial discrimination in capital sentencing, and the financial costs associated with the death penalty. Among Catholics working to end the death penalty, however, the moral questions about state killing have long been a central focus.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops focused on morality in its own campaign to end capital punishment, which was launched in 2005. And from time to time, popes have made special appeals to government officials in the U.S., asking them to spare the life of someone awaiting execution.

Legal historian Sara Mayeux argues that Catholic anti-death penalty activism in the U.S. has been less intense than anti-abortion work. Nevertheless, the impact of the church is reflected in the fact that in the past 50 years, Catholic support for capital punishment fell more than it did among evangelicals, mainline Protestants, Black Protestants and other religious groups.

In December 2024, as the term of President Joe Biden, a devout Catholic, was coming to a close, the Catholics Mobilizing Network, which advocates against capital punishment, called on the president to commute the sentences of the 40 people then on federal death row. Francis, too, publicly prayed for their sentences to be commuted.

Biden did so for 37 federal death row inmates, changing their sentences to life in prison without parole.

Anti-death penalty superstar

As the church’s official position against capital punishment has evolved, Prejean has been a consistent voice asking Americans to recognize and respond to the humanity of all those touched by murder. She is, in words I am sure she would resist, a superstar in the movement, thanks to her countless public appearances, interviews, protests and actions to lobby legislators.

In 2021, she wrote, “I’m on fire to abolish government killing because I’ve seen it far too close-up, and I have a pretty good idea by now how it works – or doesn’t.”

Thirty years ago, “Dead Man Walking” gave its viewers a chance to see capital punishment “close-up.” It didn’t preach or hit anyone over the head with an overtly abolitionist message. Instead, it asked viewers to see the death penalty from many sides and make up their own minds about whether anyone should be put to death, even for the most horrible crimes.

Between then and now, America has undertaken precisely the kind of conversation about capital punishment that the film exemplified and inspired.

Austin Sarat does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Trump says climate change doesn’t endanger public health – evidence shows it does, from extreme heat

Climate change is making people sicker and more vulnerable to disease. Erasing the federal endangerment…

FDA rejects Moderna’s mRNA flu vaccine application - for reasons with no basis in the law

The move signals an escalation in the agency’s efforts to interfere with established procedures for…

Nearly every state in the US has dyslexia laws – but our research shows limited change for strugglin

Dyslexia laws are now nearly universal across the US. But the data shows that passing a law is not the…