What Peru’s Virgen de la Puerta represents about unity and inclusion

Peruvians − including non-Catholics, some members of the LGBTQ+ community and others who are marginalized − also revere the Virgen de la Puerta.

Leo XIV, the first pope born in the United States, is also claimed by the Peruvian people whom he served for over two decades as one of their own.

Then known as Robert Francis Prevost, he lived and worked in the cities of Trujillo and Chiclayo in northern Peru. In Chiclayo he served as bishop from 2015-2023. Trujillo is a few hours south of Chiclayo, where the pope lived for a decade.

His ministry there is particularly exciting to me because I also lived in northern Peru, during a service year with the Marianist Family between my undergraduate experience at the University of Dayton and my first year of full-time ministry. The Marianist Family was founded in response to specific needs in postrevolutionary French society. Composed of lay people and vowed religious sisters, brothers and priests, it emphasizes devotion to Mary and a communal lifestyle as a distinctive way of living out one’s Roman Catholicism.

About a two-hour bus ride away from Trujillo lies the mountainous town of Otuzco, where I lived with other members of the Marianist Family – a place that would later become a significant focus of my research as a lay Marianist and Mariologist. An image of Mary – La Virgen de la Puerta – now housed in a shrine church, has been venerated and revered in the community for over 300 years.

The majority of those who maintain a devotional relationship with this image, both local or from the surrounding villages, are part of the Catholic religious majority in Peru. But some other Peruvians – including non- Catholics, some members of the LGBTQ+ community, and others who are marginalized, such as former prisoners and migrants – also revere her. Many of the devotees do not live near Otuzco but maintain a spiritual relationship with La Virgen de la Puerta.

The founding of Otuzco

The Augustinians – the religious congregation of brothers and priests that Leo XIV is a member of – settled in Otuzco in 1560.

As part of the founding of the town, the Augustinian Fathers placed the town under the protection of Mary, the mother of Jesus. They acquired a Spanish image, a statue of Mary made mostly of wood, and selected Dec. 15 to celebrate her locally. This tradition has continued since 1664, about 100 years after the Augustinian Fathers settled in Otuzco.

Frequently riddled by threats of pirates and other dangers, the people of Otuzco prayed fervently to this image of Mary for protection.

During one particular threat to their safety, around 1670, they took this image into the streets in procession to protect their town. They placed this image of Mary above the door of the church in the center of town and called the image “Nuestra Señora de la Puerta” – transliterated into English: “Our Lady of the Door.”

Contemporary pilgrimage in Otuzco

In modern times, the fiesta of La Virgen de la Puerta is lavishly celebrated in the town of Otuzco, where thousands of faithful descend upon the mountain community for the multiday fiesta patronal, a festive celebration that honors the patron saint to whom a site is dedicated or entrusted.

The fiesta patronal of La Virgen de la Puerta begins annually on Dec. 14, with the principal day observed on Dec. 15, and concludes on Dec. 16.

During the days of the fiesta, the road between Trujillo and Otuzco is transformed into a pilgrimage route. The purpose of the journey can vary from pilgrim to pilgrim, yet it often reflects a deeply personal act of devotion.

Some pilgrims arrive from Otuzco, Trujillo and neighboring villages, while others travel long distances – in Peru or from abroad – to honor La Virgen de la Puerta. Some pilgrims journey the roughly 50 miles (over 80 kilometers) between Trujillo and Otuzco on foot.

I personally made this journey with a group of fellow pilgrims, the very people I was living among and ministering with during my service year in Peru. My pilgrimage involved a backpack with basic medical supplies for the group. After an overnight walk to Otuzco in camping pants, a T-shirt, hat and sneakers, I arrived before the image of Mary with quarter-size blisters on my feet.

Some pilgrims, unlike me, mark the final kilometers of their journey by advancing to the shrine through the streets on their knees.

Devotion outside Otuzco

In addition to the thousands who descend on the town of Otuzco each year for the celebration, there are those who are deeply devoted to La Virgen de la Puerta but do not or cannot make the journey to the shrine. Their celebrations take place at times at a great distance from Otuzco.

Among them are members of the LGBTQ+ community, who to this day remain marginalized in broader Peruvian and Catholic culture. Although members of the LGBTQ+ community reside throughout Peru, the neighborhood of Cerro El Pino in Lima has historically been the site of a festive celebration in honor of La Virgen de la Puerta, which many community members observe.

Differing communities come with differing needs to La Virgen de la Puerta. The LGBTQ+ community in this particular neighborhood believes she has protected them throughout their history. During the early years of the AIDS epidemic in the 1990s, when over 10% of the male population in Lima was infected by HIV, members of this community sought the protection of La Virgen de la Puerta for their physical health. Although some people died from AIDS, others continued to participate in the rituals of the fiesta to honor her protection over time, even amid their suffering. They wore special costumes, sang and performed the dances that have been part of the fiesta patronal for over 300 years.

Francisco Rodríguez Torres is a Peruvian photographer who lives in the capital city, Lima, but has roots in the northern region where the image of La Virgen de la Puerta is located. He is one of those who has documented the activities of the fiesta patronal both in Otuzco and in Lima in his text La Mamita de Otuzco.

He writes both about the local faithful as well as those who venerate the image from a distance. In his Spanish language text, he has documented that La Virgen de la Puerta is considered a mother by groups who find themselves on the margins of society. These groups include those who are part of the LGBTQ+ community, the poor, former prisoners and migrants. They “hope to find in her gaze a consolation,” he explains.

Devotees bring their special petitions before La Virgen de la Puerta: They ask for her support in making decisions and for their everyday needs. Some even pray for miraculous healing.

Echoing this sentiment of finding hope in La Virgen de la Puerta, Pope Francis, during his apostolic journey to Peru, crowned La Virgen de la Puerta and gave her the title of Mother of Mercy and Hope. In his address during a special prayer service in Trujillo on Jan. 20, 2018, Francis recounted that La Virgen de la Puerta has defended and protected all of her children throughout history.

Leo, following the example of Francis, has focused on the importance of dialogue and peace. In his first message from the balcony upon being announced pope he said that members of the Catholic Church must build “bridges, dialogue, always open to receive like this square with its open arms, all, all who need our charity, our presence, dialogue and love.”

I believe that La Virgen de la Puerta – a source of mercy and hope for all her devotees, regardless of whether they have been historically marginalized or excluded – offers an example to the world community of the greater unity with one another that Leo XIV is seeking to prioritize.

Caitlin Cipolla-McCulloch does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Abortion laws show that public policy doesn’t always line up with public opinion

Polls indicate majority support for abortion rights in most states, but laws differ greatly between…

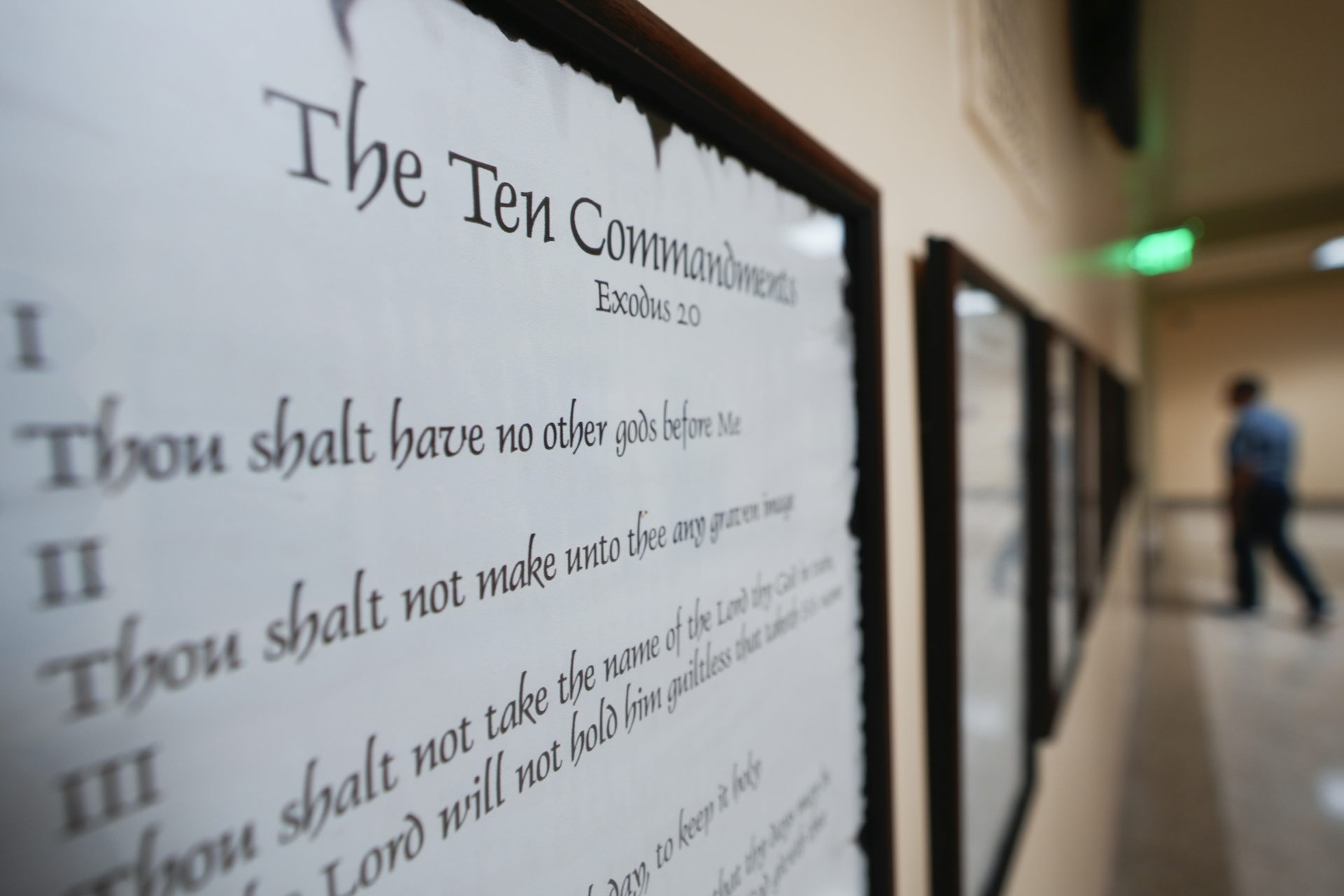

Baptists have helped shape debate about religious freedom for over 400 years – up to today’s 10 Comm

The phrase ‘separation of church and state’ dates back to a letter from Thomas Jefferson to a Baptist…

How Dracula became a red-hot lover

Count Dracula was originally a rank-breathed predator. His transformation into a tragic romantic mirrors…