‘Agreeing to disagree’ is hurting your relationships – here’s what to do instead

‘Looping’ and ‘reframing’ are two techniques that can help build understanding in stressful disagreements.

As Americans become more polarized, even family dinners can feel fraught, surfacing differences that could spark out-and-out conflict. Tense conversations often end with a familiar refrain: “Let’s just drop it.”

As a communications educator and trainer, I am frequently asked how to handle these conversations, especially when they involve social and political issues. One piece of advice I give is that “agree to disagree,” or any other phrase that politely stands in for “stop talking,” will not restore harmony. Not only that, but it could also do permanent harm to those important family bonds.

‘No-go’ topics

Conversation is the currency of relationships. When families talk about anything – from “What are your top five favorite movies?” to “What possessed you to load the dishwasher like that?” – they are not just exchanging information. They are building trust and creating a shared story that deepens the relationships within the family unit.

According to communication researcher Mark L. Knapp’s model of relationship development, all relationships have a life cycle. People come together and solidify their connection through five stages, from “initiation” to “bonding.” But many relationships eventually come apart, going through five stages of breakdown.

No relationship is as linear as the model assumes, but it can help pinpoint potential danger zones – moments when a bond is at risk of coming apart. One stage, in particular, illustrates why avoiding these hard conversations is so dangerous: “circumscribing.”

Imagine circumscribing topics of conservation with yellow police tape around them – topics that almost instantly trigger conflict. Having a few of these “no-go” topics in a relationship probably will not doom a marriage or cause family estrangement. However, marking too many ideas as off-limits makes it easier for people to avoid conversation altogether.

Circumscribing is one of the “coming apart” stages in Knapp’s model. If problems aren’t addressed, a relationship can keep sliding down the slope toward the last stage: termination.

We need to talk

Sadly, this estrangement from loved ones is not a theoretical problem. In a 2022 poll of 11,000 Americans, more than 1 in 4 people reported that they were now estranged from close family.

What’s more, these relationships are not always replaced by other close ties. About half of Americans say they only have three or fewer close friends. In 2023, then-Surgeon General Vivek Murthy declared widespread loneliness and isolation an “epidemic.”

Social connection is a basic human need. Relationships do more than provide support; they play a key role in how people define themselves. According to psychology’s “social penetration theory,” conversation with close family and loved ones deepens relationships while helping people learn to articulate their deepest values.

So if “agree to disagree” is not the answer, what is?

There is no one-time process that will fix all conflict over the course of a family dinner. These techniques take time, patience and compassion – all things that can be in short supply amid conflict. However, there are two techniques I not only recommend to others, but I use in my own conflicts: “looping for understanding” and “reframe and pivot.”

Getting in the loop

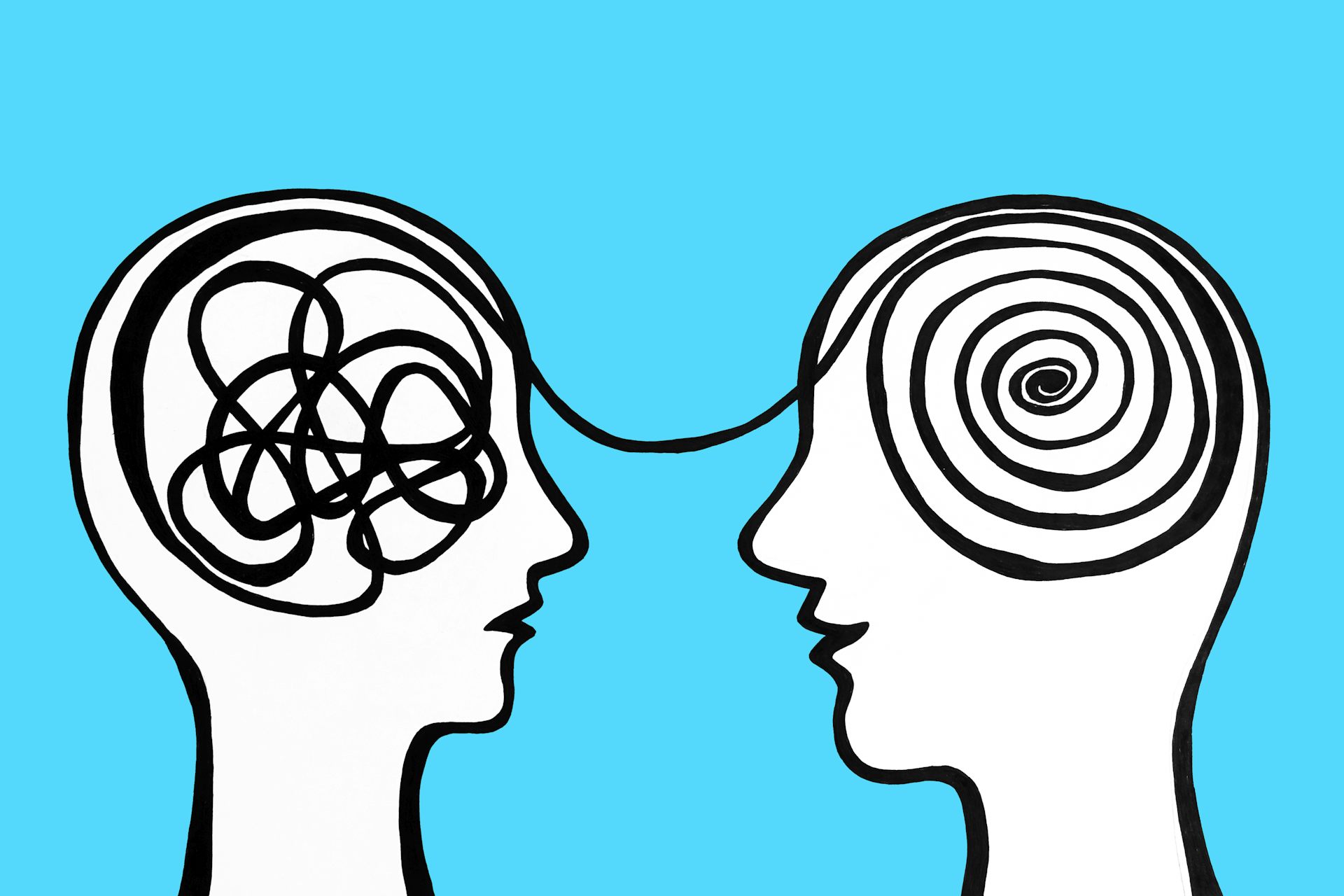

Looping, which was originally developed for legal mediation, helps both people in a conversation understand each other. Feeling misunderstood tends to escalate conflict, so this is a great starting place.

During a “loop,” each person uses active listening, meaning they pay careful attention to what their partner is saying without judgment or interruptions. Then the listener shows their understanding by using what’s called “empathic paraphrase”: restating what they heard from the speaker, but also what emotions they perceived. Finally, they ask the original speaker for confirmation.

That might sound something like this:

So if I understand what you are saying, you think that people should not have to get a flu shot at your office because you are not sure if it’s effective, and you’re frustrated that you are being told what to do by your company. Do I have that right?

If the speaker says no, then the listener “loops” by asking them to explain what they got wrong, and tries to paraphrase again. The participants keep looping until the answer to “Did I get that right?” is an emphatic “yes.” This practice ensures that both people are sure of the actual issue at hand.

Looping has other benefits, too. In one study, emphatic paraphrasing not only made participants less anxious but also made the speaker see the paraphraser in a more positive light. Feeling fully heard and understood can go a long way to turning down the heat on difficult conversations.

Framing common ground

However, that understanding may not be enough. Once both parties understand each other, another technique, “reframing,” can help pivot the conversation away from confrontation and move toward resolution.

In reframing, the speakers find and discuss a single point of agreement. By emphasizing what they agree about, instead of what they disagree about, they look for a starting place to tackle the problem together, instead of facing off.

For example:

I think you and I can both agree that we want to keep the family safe. However, I think we disagree about what role having a gun in the house would play in that safety. Is that right?

Finding a point of agreement is not always possible. However, this reframing presents both communicators as having a key shared value – a starting place for a more constructive discussion. Reframing also moves the conversation away from inflammatory language that could automatically reignite the fight. `

No magic bullet

No technique will ever be a perfect, one-size-fits-all solution for every relationship – or a quick fix. Careful communication can be mentally exhausting, and pressing pause is always OK:

I don’t think we are going to solve our nation’s financial issues tonight, but thank you for talking about it. Let’s keep doing it. But for now, I think there’s pie. Want some?

It’s also important to accept that not all relationships can or should be saved. However, it is always good to know that the relationship ended for a clear reason, and not over a misunderstanding that was never addressed.

Hopefully, though, these tactics will help keep communication open and relationships healthy, no matter what topic is brought up at dinner.

Lisa Pavia-Higel is affiliated with Braver Angels, a non-profit organization that facilitates conversations across the political divide. She is no longer active in the organization but was trained as a workshop facilitator.

Read These Next

How transparent policies can protect Florida school libraries amid efforts to ban books

Well-designed school library policies make space for community feedback while preserving intellectual…

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

How Dracula became a red-hot lover

Count Dracula was originally a rank-breathed predator. His transformation into a tragic romantic mirrors…