The ‘sacramental shame’ many LGBTQ+ conservative Christians wrestle with – and how they find healing

Queer Christians often hear a message that they’ll be accepted in conservative churches so long as they deny part of themselves.

Kai found Jesus as a teenager. A person of white and Hawaiian descent, Kai now goes by gender-neutral pronouns and identifies as “māhū,” the traditional Hawaiian term for someone in-between masculine and feminine. But when they first became Christian, the high-schooler identified as gay – and was committed to celibacy.

Kai – a pseudonym to protect their privacy – embraced their church’s “welcoming but not affirming” teachings about LGBTQ+ people, agreeing that same-sex intimacy was incompatible with being Christian. It felt good to be sacrificing for the Lord, Kai recalls. But they eventually realized they were harming themself.

“I found myself unconsciously shutting down connection,” Kai told us. “Inside, I was crumbling in every moment because I was so fervently policing myself.”

Kai believed – and their church taught – that God’s own love is a gift, freely given. Nevertheless, they still felt that to be worthy of that love, Kai had to “surrender” their orientation and need for emotional connection, even with friends.

“It took me a long time to be able to look back on that and say, ‘Those were days when I hated myself,’” Kai said. “I hated myself for the sake of demonstrating how much I loved God.”

Kai began to reflect on what it meant to be Christian and concluded that Jesus didn’t have a problem with same-sex marriage, or gender beyond clear ideas of “male” and “female.” Christian “friends” quietly cut Kai out of their lives.

As a sociologist and a philosopher, we’ve worked together to understand the experiences of LGBTQ+ conservative Christians. Kai’s story illustrates a dynamic that in our 2025 book, “Choosing Love,” we call “sacramental shame.”

In Christianity, the word “sacrament” often refers to a particular rite, like baptism, that provides a tangible sign of God’s presence. Many of the LGBTQ+ Christians we spoke with felt that conservative congregations expected them to demonstrate shame for their identity to prove they hadn’t turned their backs on God – that God was still present in their lives.

Weight of shame

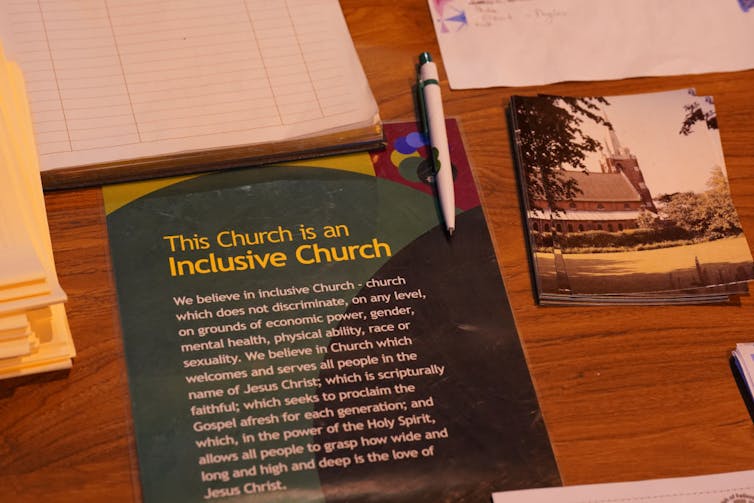

Some Protestant denominations fully affirm LGBTQ+ identities, same-sex marriage and gender transition, and other churches are split.

But when we learned that LGBTQ+ people and their allies were advocating for change in conservative churches, we wanted to hear their stories.

In interviews and fieldwork, LGBTQ+ evangelicals told us that their churches often treated being cisgender and straight as though it were more important than the Ten Commandments. In some congregations, being LGBTQ+ is treated as an especially grave sin. But since people can’t change their sexual orientation or gender identity at will, treating these things as sins creates an experience of endless shame.

In the “sacramental shame” dynamic, churches require LGBTQ+ people to feel and display shame as the sign that they have not rejected God. Their churches, families and friends more or less require them to act as though their very capacity to love others, and to recognize the truth about themselves, is a danger to the people they love.

As one person recalled, “there were a lot of [friends] that I cut off. And I thought I was endangering them. I thought that I was going to poison them.”

Feeling unworthy of the love of God and other people can make people feel like their lives are not worth living. We heard about countless struggles with addiction, depression and suicide attempts – and sometimes even physical symptoms, like unexplained asthma attacks or autoimmune disorders that developed as LGBTQ+ people wrestled with the stress of trying fervently to be worthy of love.

Queer Christians of color

Sacramental shame isn’t easy for anyone, but often it can be more complicated for Black or Indigenous Christians and other Christians of color. In part, that’s because centuries-old racist tropes often depict minority groups in a sexualized way, as “promiscuous” or “exotic.” Not wanting to affirm those stereotypes can make it harder for LGBTQ+ Christians of color to navigate life.

Kai, like many Christians, was drawn to the faith’s message of love and justice for the oppressed. Religion can offer support and strength for dealing with the realities of racism. But that can sometimes turn into a pressure to disprove racism by behaving as “respectably” as possible.

A Black, bisexual pastor we’ll call Imani grew up in a church that quietly supported LGBTG+ people, but she never knew it. As a young person, Imani worried that her own sexuality might cause trouble for her mother, who had already been through a lot:

I was scared of embarrassing my mother. … All I could think about was the swirling doom that would be, if people found out. … I never even thought for a second that it was an option.

Some white respondents, too, feared that coming out would embarrass their parents. But for Imani, silence about her sexuality seemed necessary to protect the Black community’s respectability, as well as her family’s belonging in the church.

We also met Darren: a Black, gay man who was urged to try to fight being gay. His pastor’s ideas about how to “fix” Darren involved having him live in an out-of-state church building for four years, sleeping on the altar and fasting two days a week.

It ended when Darren heard Christ telling him to stop hiding from life. So he went home, and his pastor told the church not to talk to him.

Shifting views

Some conservative Christians, including allies who aren’t LGBTQ+, are starting to change the conversation – and their own views.

In 2024, New Testament scholar Richard Hays and his son Christopher Hays drew ire from some fellow evangelicals by publishing a book arguing that God’s mercy creates room in the church for LGBTQ+ people. Before them, evangelical leaders such as Tony Campolo, David Gushee and James Brownson had also changed their minds.

Leaders or laypeople who have rethought the issue often pointed out to us that Jesus said all of the Ten Commandments come down to loving God and your neighbor. Some said their views began to shift when they remembered to exercise humility, realizing that they might not know everything about gender, sexuality and God’s plan.

For example, the Book of Genesis says that God created male and female; it also says God created day and night, and sea and dry land. But as transgender Bible scholar Austen Hartke writes in his 2018 book “Transforming,” recognizing night and day doesn’t preclude sunsets. The fact that there are seas and dry land doesn’t mean marshes are abominable.

As Kai tried to share God’s love with other LGBTQ+ people, Kai came to realize that their church’s expectation for all LGBTQ+ people to be celibate “wasn’t just hurting me; it was hurting other people.” Kai decided that “As holy as this feels, it’s not the spirit of the Jesus I fell in love with when I became a Christian.”

Humility is not the opposite of pride; it is a realistic awareness of your gifts and your limitations. When LGBTQ+ people celebrate pride, they are celebrating the often hard-won knowledge that they are human beings, worthy of love.

Dawne Moon received funding for this project from the Templeton Religion Trust, the Association for the Sociology of Religion, the Louisville Institute, and Marquette University. In the course of conducting research for the project this draws from, she served from 2015-2017 on the board of the Center for Inclusivity.

Theresa Tobin received funding from the Templeton Religion Trust and Marquette University.

Read These Next

Algorithms that customize marketing to your phone could also influence your views on warfare

AI systems are getting good at optimizing persuasion in commerce. They are also quietly becoming tools…

Colleges face a choice: Try to shape AI’s impact on learning, or be redefined by it

Colleges and universities are taking on different approaches to how their students are using AI –…

Meekness isn’t weakness – once considered positive, it’s one of the ‘undersung virtues’ that deserve

The word ‘meekness’ might seem old-fashioned – and not a positive trait. But understanding its…