What ancient animal fables from India teach about political wisdom

‘Pañcatantra,’ a striking collection of animal fables in which birds, lions and others speak and reason as humans do, guides leaders through 3 ethical positions.

In today’s volatile world, where wars can be fought over territory, commerce can be abruptly subjected to tariffs, and friendly nations can turn hostile after a single election, political leadership is more consequential than ever. So, one must ask, what makes a leader effective, and how should we choose who should lead?

Classics such as Aristotle’s “Politics,” Confucius’ “The Analects” and Machiavelli’s “The Prince” offer compelling visions of proper governance. But there is another ancient source of political wisdom – the classical Indian tradition – which is not as well known in the West.

I am a scholar of Indian religions, and in my 2025 book “Brahmins and Kings,” I examine various narrative works written in Sanskrit – the classical language of India – which deal with political theory. Among them, Viṣṇuśarman’s “Pañcatantra” stands out. It is a striking collection of animal fables from perhaps around 300 C.E. in which birds, lions and others speak and reason as humans do.

The “Pañcatantra” stories are parables that teach how to negotiate sometimes brave, sometimes cruel, sometimes clever and sometimes naïve friends and enemies alike. These stories weigh three ethical positions and settle on one as best for politics.

Doing what’s right

First, one might seek to guide leaders by the “ethic of deontology.” This theory suggests people are duty-bound to act morally, because being good is an end in and of itself.

Although Indian theorists knew this ethic well, they were also aware that those with power often need inducement for doing the right thing, for – as the saying goes – power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Doing “the right thing,” “for its own sake,” can be naïve in the political arena.

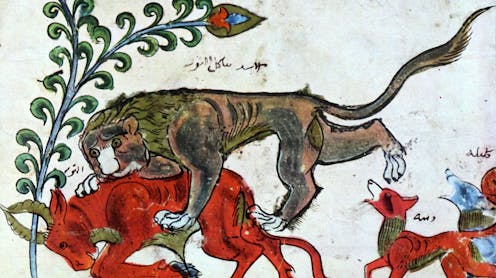

So goes the story in the third book (of five) in the “Pañcatantra,” titled “War and Peace.” A kingdom of owls was crushing the crows in battle, until a clever crow, a counselor named Ciraṃjīvin, or “Long-life,” cooked up a ruse.

He smeared the blood of his lost brethren on his body, plucked his own feathers and scarred himself with wounds. Approaching the king of the owls in this sorry state, he claimed the crows had violently thrown him out for suggesting they should sue for peace.

Now, he lamented, his only wish was revenge – alliance with his former enemies so as to punish his erstwhile companions. The counselors to the king of the owls advise him that it is simply right to harbor those in distress, so the owl king does so on principle.

Patiently licking his manufactured wounds in the owls’ kingdom, Ciraṃjīvin then spied all its defenses and weaknesses, divined the opportune time for the crows to invade, and led them to conquer the owls.

A friend in need is a friend, indeed

If the story of the owls and the crows teaches that naïvely choosing what’s right is unwise, then why not drop morality altogether? Why not ruthlessly pursue whatever produces results? This is the second view of political leadership: double-cross, cheat, bully, cajole, break the conventions and rules – do whatever works!

Indian political theorists thought of this, too, and their very definition of good political rule is that it produces results for the people. But they also rejected unbridled ruthlessness, because they knew that such Machiavellianism was too blunt an instrument for political affairs.

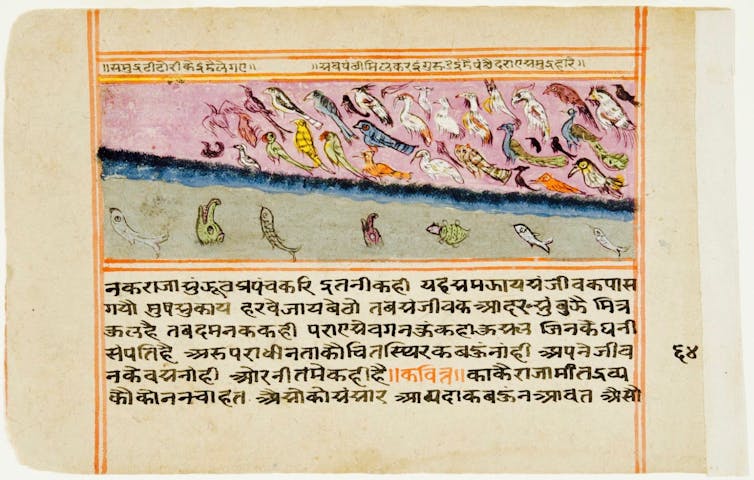

Consider the “Pañcatantra’s” second book, titled “On Securing Friends.” Here we meet another crow, this one named Laghupatanaka, or “Light Wing” – a nimble but lonely bird who witnesses friendship in action. He sees a hunter trap a dule of doves in his net. But their leader directs the bevy to pull all together.

As one they lift up the net and wing it a distance, the fowler chasing all the while on the ground. Soon, they land where they can meet up with their friend, a mouse named Hiraṇyaka, or “Eager for Gold,” who chews through the net as a dove never could, and they escape before the fowler arrives.

Laghupatanaka knows he, too, might be hunted. So he seeks out Hiraṇyaka, though they are said to be “natural enemies” because crows eat mice. But Laghupatanaka promises loyalty, and he never betrays Hiraṇyaka, even though he is the stronger one.

Gradually, they add to their company a wise turtle and a beautiful deer and prosper together on a paradise island until a trapper invades their home. Each plays a role in fooling their foe, who captures the turtle, while the deer, heeding the turtle’s good counsel, manages a sly escape.

To free the turtle, the deer plays dead while the crow mimics pecking at his eye. The trapper leaves the turtle behind, distracted by this bigger prize. Then Hiraṇyaka the mouse cuts the net holding the turtle, who crawls away as the decoy deer and the crow each take flight.

Deer, crow, turtle and mouse each possess an innate ability, and together they save all from harm.

The moral of this story is clear: Teamwork is effective, and successful leaders, no matter how powerful, thrive by relying on friends. As the well-known adages go: Two minds are better than one; many hands make for light work; a friend in need is a friend, indeed.

Business is business, but how?

Nevertheless, it’s a competitive world, and some friends are greedy or false, as the story of the owls and the crows suggests. But if both pure morality and pure Machiavellianism are sometimes unwise, what third option could there be?

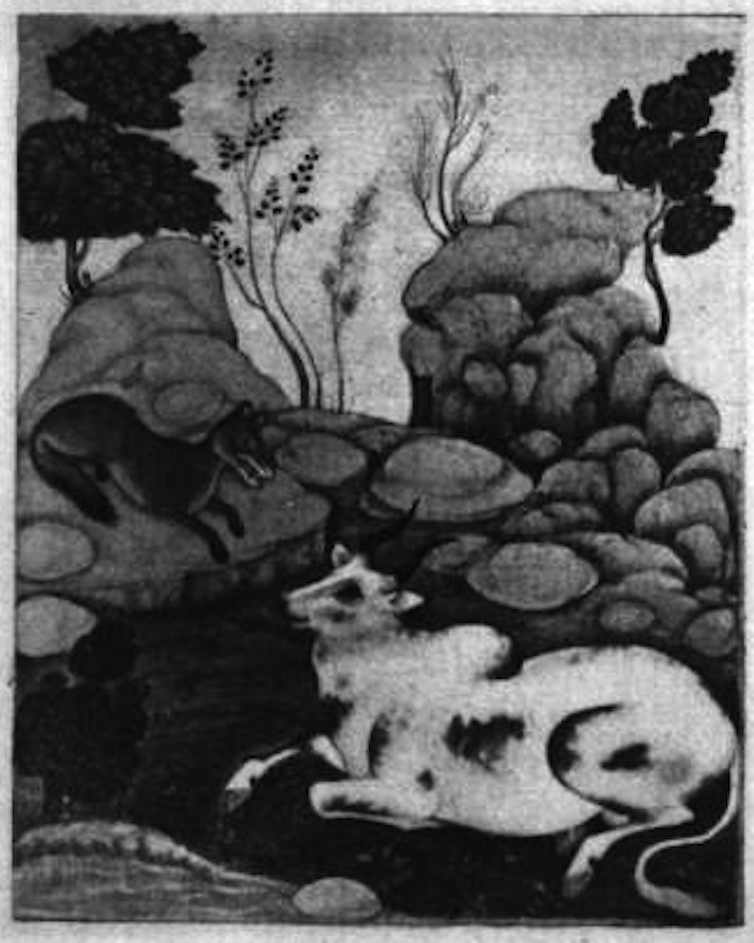

Consider the story of the first book of the “Pañcatantra,” the tale of the foolish lion king who is tricked into fighting a natural ally. The king of the forest was once frightened by the sound of a bull. His advisers, the jackals, rightly judge the bull to be harmless, and they convince the two to meet. In time, the lion and bull became close friends – so much so that the lion stopped hunting, and the animals in his retinue began starving.

The jackals then went to the king with a ruse: They told him that the bull was plotting to kill him; they manipulated the bull in similar fashion. In the fight that followed, the lion was injured, but the bull was killed. There was enough meat to feed everyone, and the jackals were promoted, because the lion king falsely believed they helped him avert a plot.

Now, one might wrongly conclude that the moral of this story is power through strength. But the “Pañcatantra” makes clear that there’s more to it: The bull was a true friend who had helpfully counseled the king. It was the jackal advisers who betrayed the lion with their manipulative story, which won them undue power and wealth at the cost of a friend.

Enter the third, and best, of the trio of political theories: virtue ethics. Leaders should cultivate wisdom. Chasten passions and impulses, the Indian texts counsel, in order to be able to distinguish opportunity from danger, friend from pretender, good advice from folly. Be discerning so as to see the world as it is and can be. Be good in order to do well in the world.

Wisdom in action

In Indian political theory, then, the answer is as simple as heeding the wisdom of parable stories: Do what is right, with the right measure, at the right time. Needless to say, this is more easily said than done. And one cannot force a leader to be chastened or wise.

Voters can, however, favor those who pursue self-restraint. For if leaders must be thoughtful to be wise – and thus open the road to results – then voters should seek those who listen and learn so as to be able to know just what to do and when.

This is the counsel that the classical Indian tradition offers contemporary voters. But to see who has just this virtuous discretion, voters will need a touch of that wisdom themselves.

John Nemec does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?

Picky eating starts in the womb – a nutritional neuroscientist explains how to expand your child’s p

While genes do influence some food preferences, positive experiences can help make new tastes easier…

Algorithms that customize marketing to your phone could also influence your views on warfare

AI systems are getting good at optimizing persuasion in commerce. They are also quietly becoming tools…