Insects are everywhere in farming and research − but insect welfare is just catching up

There’s no single, simple way to assess whether bugs feel pain, but research is giving scientists a better understanding of their abilities.

Did you know your lipstick might be made from beetles? Or that some cat food may soon be made from flies?

People farm insects for all sorts of reasons: Farmers rear bees to pollinate billions of dollars of crops, textile companies raise silkworms for their cocoons, and cosmetic companies use cochineal beetles for dyes. Researchers also put insects to work in labs: Fruit flies have revolutionized genetics, cockroaches provide insights into neurobiology, and ants inspire AI-driven robots.

On top of that, medical companies raise blowfly larvae to clean wounds, desert locusts for compounds that might help reduce the risk of heart disease, and lac insects for their secretions, which are used to coat pills.

All told, trillions of insects are farmed each year across the globe – more than all other livestock combined. Each year, producers rear some 2.1 trillion black soldier flies alone – and, if industry trends hold, will be rearing three times as many in 2035. Currently, roughly 30 times as many insects are produced as the most-farmed “traditional” farm animal: the chicken.

As an ethics professor, I think this raises pressing questions about what it means to treat insects humanely. Several years ago, I was skeptical that these questions were worth asking, as most questions about animal welfare center on pain – and I didn’t think there was much chance that insects could feel it. However, as science has uncovered more about insects’ abilities, the emerging field of insect welfare seems increasingly important.

New science of animal minds

In the 17th century, many scientists believed that all nonhuman animals were mere machines that behaved as if they felt pain but didn’t actually experience it.

While most scientists have long abandoned this view, researchers have not identified a definitive test for the capacity to feel pain in any nonhuman animal. There is no known brain structure or pattern of neural activity whose presence or absence settles the question. There’s no single behavior that decisively establishes pain, either.

So, researchers look for several markers of pain that, taken together, support taking this possibility seriously. Some of these markers are neurobiological, such as specialized damage receptors and regions of the brain that integrate those signals with information from other senses. Some are behavioral, such as an animal making trade-offs between avoiding harm and pursuing rewards.

Fruit flies, for example, are willing to cross electrical barriers that give them mild shocks to reach food. However, they won’t cross barriers that give them stronger shocks, even when very hungry. This suggests that there’s something more than simple reflexes at work: The animal is weighing different motivations to make a decision.

Evidence like this keeps accumulating. Some bees can remember experiencing high heat and weigh this against the reward of sugar when it’s offered in hot containers. They also display emotion-like states, in that they respond to cognitive bias tests the way other animals do. These tests are used to assess how animals’ emotions influence their cognitive processes: Like people, animals handle uncertain situations differently if stressed or satisfied.

Fruit flies become averse to temperatures that were once innocuous after researchers amputate their legs, just as some injuries in humans can lead to heightened pain sensitivity. Tobacco hornworm moth larvae and cockroaches tend to their wounds when hurt. And contrary to a common myth, many male praying mantises try to avoid being eaten by females; they don’t always just continue mating.

Again, no single marker – or even the lot of them – proves that insects can feel pain. However, the accumulated evidence suggests that there’s at least a realistic possibility. This position is reflected in two scientific consensus statements: the 2012 Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness and the 2024 New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness, which are attempts to summarize the state of knowledge about many groups of animals.

Humane practices?

It’s widely acknowledged that it’s wrong to cause unnecessary pain in animals – an imperative codified in the ethical principles that U.S. federal agencies consult when making regulations about research. So, if insects can feel pain, as most Americans believe, then there is an ethical reason to protect their welfare.

Of course, it isn’t certain that they can feel pain. So, precautionary reasoning becomes important: taking steps to reduce the risk of causing harm that are, in some sense, proportional to the magnitude of the risk. In other words, people who rear insects should take modest steps to reduce the risk that they are causing more pain than they need to cause.

On some insect farms, a potential concern is injuries from cannibalism and aggression, which occur at greater rates when animals such as crickets are crowded together. The issue crops up in other farming systems as well: Chickens harm their flockmates when they don’t have sufficient room.

There are also worries about slaughter. Typically, a humane death is fast, but many insects are killed using very slow methods, such as baking and microwaving. Grinding and boiling, by contrast, may be much quicker.

In lab research, one potential concern is performing live dissections, once known as vivisection, without anesthetics or analgesics. The practice has been almost universally abandoned for vertebrate animals but is still routine with some insects. People have described many cases of insect neglect to me, including times when researchers have accidentally let insects starve or become fatally dehydrated after experiments conclude, rather than euthanizing them.

Granted, it’s hard to be sure that any particular practice causes pain. If there’s a realistic possibility, however, then it’s worth considering alternative practices.

As scientists have suggested, insect producers could reduce the number of animals in each container to reduce problems associated with crowding. They could investigate strategies for stunning insects before processing them, just as other animals are stunned before slaughter.

In most countries, insect researchers are not legally required to follow the standard ethical guidelines for other animal researchers. But there is nothing to prevent insect researchers from following them voluntarily. These international guidelines recommend avoiding the use of live animals entirely when possible; using fewer live animals when they do need to be used; and refining practices to minimize the risk of pain and distress, such as giving insects anesthesia before dissection.

It’s possible to treat insects more humanely. And since they may be able to feel pain, I believe it’s important to take reasonable steps to do so.

Bob Fischer is on the board of the Insect Welfare Research Society and the Arthropoda Foundation.

Read These Next

Denmark’s generous child care and parental leave policies erase 80% of the ‘motherhood penalty’ for

Two researchers found that Danish government benefits do not fully offset moms’ lost earnings. But…

Trump’s climate policy rollback plan relies on EPA rescinding its 2009 endangerment finding – but wi

A federal judge dealt one blow to the effort when he found the administration had violated the law in…

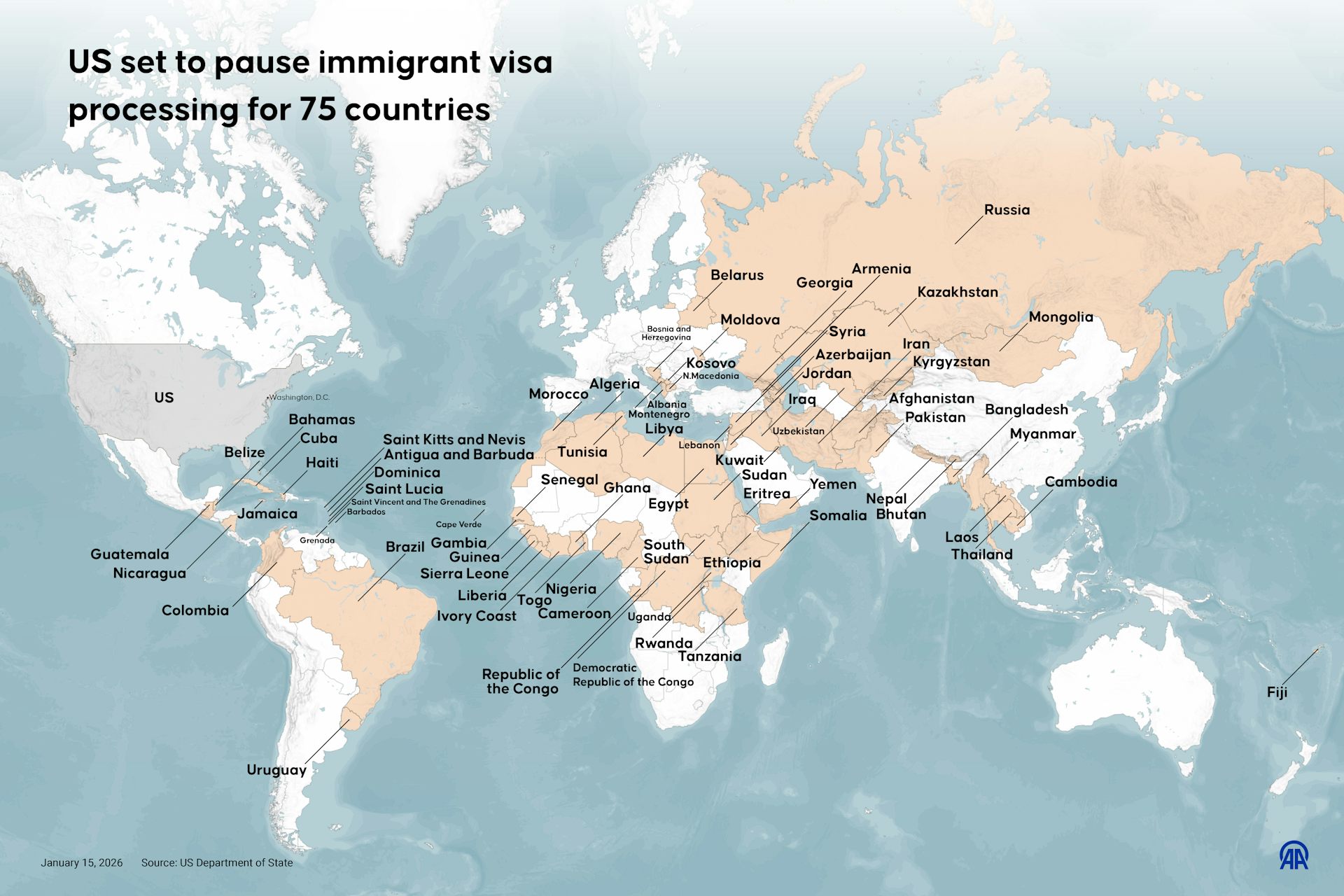

Suspending family-based immigrant visas weakens US families and the economy

Family reunification is often framed as a cost, but evidence shows it functions as social infrastructure…