Nat King Cole’s often overlooked role in the Civil Rights Movement

March 17 marks 106 years since the birth of musician Nat King Cole, whose success paved the way for future generations of Black artists.

Six decades after Nat King Cole’s death in 1965, his music is still some of the most played in the world, and his celebrity transcends generational and racial divides. His smooth voice, captivating piano skills and enduring charisma earned him international acclaim.

One of the most influential artists of the 20th century, Cole was not only a groundbreaking musician but also a quiet, yet resolute, advocate for social justice.

As an African American sacred music scholar, I have been immersed in the inseparable link between music, culture and social change for over 40 years. Examining Cole through the lens of his activism uncovers the nuanced ways in which he challenged the status quo and contributed to the Civil Rights Movement.

Beneath the polished veneer of his public image lay a deeply personal commitment to confronting racism and advocating for equality that is often overlooked.

Formative years

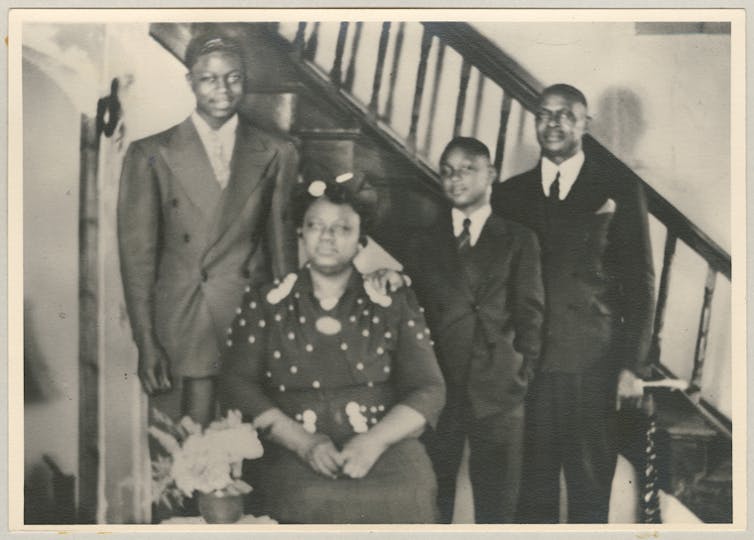

Nathaniel Adams Coles was born on March 17, 1919, in Montgomery, Alabama, to Perlina Adams Coles and Edward James Coles. Perlina served as the organist at the True Light Baptist Church and later the First Baptist Church of North Chicago, both pastored by Nathaniel’s father. She passed her love for music to her children, teaching them to play the piano and organ. Cole’s formative years were spent in church; gospel songs, hymns and spirituals formed the foundation of his musical education.

Though Cole is primarily remembered for his jazz and pop hits, the emotive power, communal emphasis and uplifting nature of Black sacred music profoundly shaped his artistry throughout his career, despite his single sacred album, “Every Time I Feel The Spirit,” released in 1959. The influence of gospel music, in particular, can be heard in his soulful phrasing and heartfelt delivery, contributing to his remarkable ability to connect with audiences.

Growing up in Chicago, he was also exposed to a rich tapestry of musical genres, including blues, classical and jazz. This eclectic upbringing laid the foundation for his versatile musical style and commercial success.

While Cole’s music was not overtly political, his very presence in the mainstream was a statement. In an era of racial segregation, he was a Black man achieving unprecedented success in a predominantly white music industry. His impeccable diction, tailored suits and sophisticated performances countered the prevailing stereotypes of African Americans as uncouth or subservient.

By embodying a poised and dignified persona, Cole communicated a powerful message: Black excellence and humanity could not be denied. As race scholar George Lipsitz writes in “The Possessive Investment in Whiteness,” “The cultural field … is a site of struggle where meanings are contested and power relations are negotiated.”

Cole’s success challenged the structural racism that sought to confine Black artists to the margins and opened doors for future generations. He acknowledged the significance of his presence on national television, recognizing it as a potential turning point for Black representation. While hesitant to explicitly label himself an activist, he contemplated the impact of his success on breaking down barriers, believing that “when you’ve got the respect of white and colored, you can ease a lot of things.”

Confronting racism

In response to critics who dismiss Cole’s legacy as apolitical, I argue that they overlook the complexity of his resistance. Several scholars have stated that in a society where overt defiance often resulted in violence or economic ruin, Cole’s ability to navigate the entertainment industry while maintaining his dignity was itself a form of activism.

Though Cole never referred to himself as an activist, he confronted racism in both overt and quiet ways. Scholars such as cultural theorist Stuart Hall and researcher Laura Pottinger define “quiet activism” as modest, everyday acts of resistance – either implicitly or explicitly political – that challenge dominant ideologies and power structures. These acts often entail processes of production or creativity.

Despite his commercial success, Cole faced relentless systemic and personal racism. In 1948, he purchased a home in the affluent Hancock Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, a move met with hostility; the local homeowners association attempted to expel him, and he endured threats and acts of vandalism.

Yet Cole refused to be intimidated. His resolve was a courageous act of resistance that highlighted the pervasive inequalities of the time.

Cole faced blatant discrimination in Las Vegas. He was often denied access to the same hotels and restaurants where he performed, forced to stay in segregated accommodations. One particularly notable incident occurred at the Sands Hotel. in Las Vegas. When the maitre d’ tried to deny service to Cole’s Black bandmates in the dining room, Cole threatened to cancel his performance and leave. This forced the hotel management to back down, setting a precedent for other Black entertainers and patrons.

Cole quietly sued hotels and negotiated contracts that guaranteed his right to stay in the hotels where he performed, a significant step toward desegregation. He also made it a point to bring his entire entourage, including Black musicians and friends, to these establishments, challenging their “whites only” policies.

‘We Are Americans Too’

Cole’s impact extended beyond the realm of music. In 1956, he became the first African American to host a national network television show, “The Nat King Cole Show.” This was a groundbreaking moment, as it brought a Black man into the living rooms of millions of white Americans every week.

Though the show faced challenges with sponsorship due to racial prejudice, it marked a significant step toward greater representation and acceptance. As historian Donald Bogle notes in his 2001 book “Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks,” “Television … became a new battleground for the image of the black performer.” Cole’s show, despite its short run, was a crucial battle in this war.

When Cole was attacked onstage by white supremacists during a concert in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1956, it underscored the physical danger Black public figures faced and galvanized Cole’s commitment to the Civil Rights Movement.

It is important to note that Cole’s support for the Civil Rights Movement was often quiet and behind the scenes. He faced criticism from some who felt he should have been more outspoken. However, his actions demonstrate his commitment to the cause of racial equality. Cole, who died in 1965 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, was a member of his local NAACP branch. He also performed at benefit concerts for the organization, raising money to support their efforts in fighting racial discrimination.

Shortly after the attack in Birmingham, Cole recorded his only song that is specifically political, “We Are Americans Too.” Recorded in 1956, the song was a powerful statement of belonging and a challenge to racial exclusion. Though it would not come close to reaching commercial success, it did serve as a powerful reminder that African Americans were, in fact, Americans. Over a half-century later, this song still resonates and speaks to the ongoing struggle for full inclusion and recognition for marginalized groups.

The juxtaposition of the refrain “We are Americans too” against the backdrop of the treatment of Black people during the Civil Rights Movement gives this song emotional weight. The very act of having to assert “We are Americans too” highlights the injustice of the situation.

It underscores the disconnect between the ideals of American democracy and the reality of racial inequality. In this context, the refrain “We are Americans too” is an act of resistance, a challenge to the prevailing social order. It highlights the hypocrisy of a nation founded on principles of liberty while denying those same liberties to a significant portion of its population. It’s a call for America to finally recognize the full humanity and citizenship of its Black citizens.

Great art, and great artists, are powerful witnesses of the times in which they live, love, work and play. Their commentary, both artistically and humanly, leaves an important record for generations. This is clearly evident in Nat King Cole.

Donna M. Cox does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Crowdfunded generosity isn’t taxable – but IRS regulations haven’t kept up with the growth of mutual

Some Americans are discovering that monetary help they received from friends, neighbors or even strangers…

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?

Algorithms that customize marketing to your phone could also influence your views on warfare

AI systems are getting good at optimizing persuasion in commerce. They are also quietly becoming tools…