Kristallnacht’s legacy still haunts Hamburg − even as the city rebuilds a former synagogue burned in

Questions about how to represent German Jews, past and present, have complicated plans to rebuild the destroyed temple.

Johanna Neumann was 8 when she witnessed a mob of local citizens and Nazis vandalizing the Bornplatz Synagogue in Hamburg. They were “shouting and throwing stones at the marvelous glass windows,” as she later said in an oral history interview. Other students at the Jewish school nearby described a mountain of prayer books and Torah scrolls lying in the dirt on the street, desecrated and set aflame.

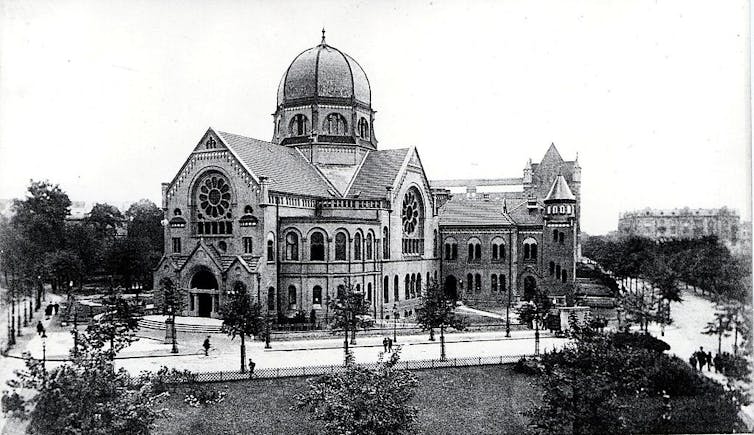

It was 1938, five years after Adolf Hitler’s reign began. The Bornplatz Synagogue, a grand neo-Romanesque building, was one of the country’s largest. Now it stood desecrated, one of hundreds of Jewish institutions damaged or destroyed in the state-sponsored pogrom on Nov. 9-10. That day came to be known as Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass, a euphemism referring to the many windows shattered.

Hundreds of Jews died from the attacks, and up to 30,000 Jewish men were sent to concentration camps. Blaming Jews for the violence, the Nazi government fined the community an impossible-to-pay 1 billion reichsmarks. In Hamburg, the Jewish community was forced to sell the damaged synagogue, which was soon demolished.

Over the past few years, the location of this former landmark has become the site of controversy as residents debated whether and how to rebuild the old synagogue, which would demolish the memorial standing there today.

As a scholar of German-Jewish history, and the ways it is remembered, I believe the plan touches an open nerve: how Germany grapples with the need to memorialize the past, while also supporting a revitalized Jewish community today. For some, rebuilding the old synagogue is a sign of Jewish life returning to flourish in the city; for others, rebuilding the site is an erasure of past trauma.

Road to remembrance

Germany’s reckoning with the Holocaust, and the responsibility to commemorate the victims, is a long and winding process. In the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, most Germans turned inward, mostly focusing on their own hardships, and did not dwell on the suffering of Jewish victims.

Catalysts for change included Adolf Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem in 1961 and the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials in 1963-1965, in which 22 camp staff were tried. Witness testimony and widespread media coverage increased awareness of the atrocities at the concentration camps and death camps. The broadcasting of the American miniseries “Holocaust” in 1979 made the past present in every West German living room. Local activists also began to uncover Jewish histories in Germany’s small towns.

A symbolic moment in Germany’s reckoning was the 50th anniversary of the November Pogrom. The 1988 commemorations were marked by a wave of events in both West and East Germany, including an opening ceremony for a Jewish museum in Frankfurt. The chancellor of West Germany, Helmut Kohl, was in attendance – a sign that attention to Jewish life and history was becoming part of a deliberate policy.

By 1988, the Bornplatz Synagogue had been mostly turned into a parking lot. One could walk through and easily forget that a center of Jewish life once stood there. But the city of Hamburg marked the 50th anniversary by unveiling a new memorial on the site. Designed by the local artist Margrit Kahl, a mosaic floor depicts the outline of the destroyed synagogue and its dome.

According to architectural historian Alexandra Klei, Kahl’s memorial was “one of the first” of its kind to mark an “empty space in the city an object of remembrance.” It now serves as an intentionally open gap in an otherwise bustling university area.

Soon after, the square was renamed in honor of Joseph Carlebach, the synagogue’s last rabbi, who was deported to Jungfernhof concentration camp near Riga. He was murdered in a mass execution in a forest nearby in March 1942.

An old-new building

In Hamburg, members of the Jewish organization that serves as the official representative to city and state institutions envision rebuilding the old synagogue – a way of revitalizing Jewish life in the same space where it once flourished.

The idea gained traction in 2019 after an antisemitic attack in a synagogue in Halle, a city in central Germany, on Yom Kippur. An online petition in support of rebuilding received more than 107,000 signatures, as well as the support of Christian leaders and local politicians.

Other synagogues have been built on the sites of destroyed ones in other German cities, such as Dresden and Mainz. These buildings were intentionally designed to look modern, never to be mistaken for the originals destroyed in the Holocaust. Nor were they displacing a significant memorial.

In Bornplatz, by contrast, the community imagined building a replica of the original, even at the potential expense of Kahl’s work.

Several dozen intellectuals, both Jewish and non-Jewish, strongly opposed this idea, arguing for the power of empty space to send a message. Rebuilding a replica synagogue on top of the memorial, they contended, would erase the memory of the destruction, as if the November Pogrom never happened.

Whose Judaism?

Whether to fill the space with an old-new building isn’t all that is up for debate. The synagogue controversy is about Jewish life in Germany today, argues Hamburg sociologist Suanne Krasmann, and about the kind of Judaism that should be memorialized.

After the Holocaust, the fall of the Soviet Union and the reunification of Germany, the demographics of the Jewish community in Germany radically changed. Today, the overwhelming majority of the roughly 100,000 people affilliated with the Central Council of Jews in Germany are immigrants from the former Soviet Union or their descendants.

In Hamburg, the main Jewish community is led by Rabbi Shlomo Bistritzky of Chabad, an Orthodox denomination with no historical roots in prewar Germany. By contrast, critics of the Bornplatz Synagogue reconstruction point out that the city has an important place in the history of Liberal Judaism and the Reform movement. Historian Miriam Rurüp, for example, drew attention to the sorry state of the former Poolstraße Temple, that movement’s first purposefully built synagogue.

Past is present

Despite the objections, the Hamburg assembly unanimously voted in 2020 in favor of rebuilding. The following year, a feasibility study concluded that the project would indeed have to relocate Kahl’s memorial, or build over it entirely.

At the same time, the report noted, “We cannot restore the historic Bornplatz Synagogue. The Bornplatz Synagogue was annihilated by the Nazis.” The new synagogue will not be the same as the 1906 building; the past cannot be rebuilt as if nothing happened.

The project is years from completion, as is a potential Jewish museum. It is unclear what form they will take. Eighty-six years after the November Pogrom, Germany is still working through its past; Hamburg’s psychological landscape remains marked by an invisible “under construction” sign.

Yaniv Feller was a Dr. Gabriele Meyer/ZEIT-Stiftung Bucerius fellow at the Institute for the History of German Jews in Hamburg over the summer of 2024.

Read These Next

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

Enforcing Prohibition with a massive new federal force of poorly trained agents didn’t go so well in

Both Prohibition and current mass deportation efforts were hastily built, staffed by people permitted…